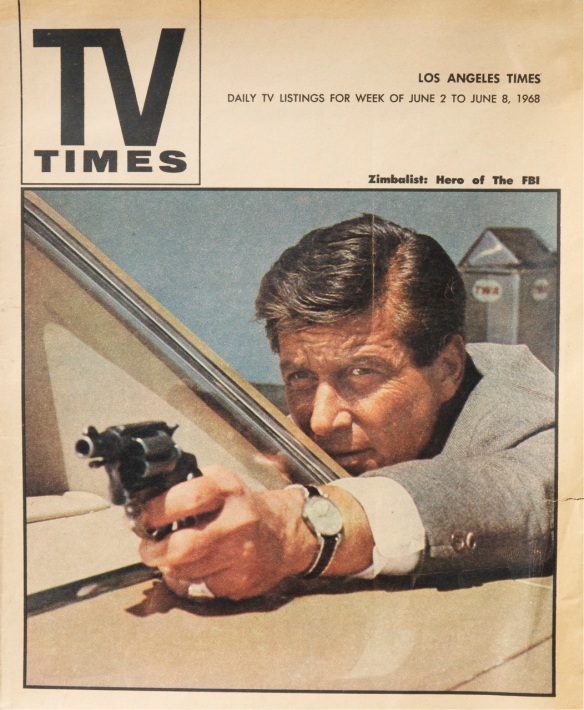

L.A. Times TV Guide cover, June 2, 1968, two days before Robert Kennedy’s assassination in Los Angeles (Jim Friedrich personal archive)

Oftener it falls, that this winged man, who will carry me into the heaven, whirls me into the clouds, then leaps and frisks about with me from cloud to cloud, still affirming that he is bound heavenward and I, being myself a novice, am slow in perceiving that he does not know the way into the heavens, and is merely bent that I should admire his skill to rise …

— Herman Melville, The Confidence Man

In Melville’s final novel, a ‘mysterious stranger’ boards a Mississippi riverboat on April Fools Day, initiating a series of scams upon the gullible passengers. Appearing in various guises, the stranger collects money for distant charities, solicits investments in get-rich-quick schemes, and sells miracle cures, all the while encouraging his marks to have confidence in the dream of better lives and a better world. He is the “winged man” who promises to carry them “heavenward.”

However, the marks soon learn that the hopes and dreams on offer are a total fraud. Melville describes the inevitable disillusion: “I tumble down again soon into my old nooks, and lead the life of exaggerations as before, and have lost the faith in the possibility of any guide who can lead me thither where I would be.”[i]

That riverboat still haunts the American imagination. We fall in love with dreams and schemes of better futures, better selves, a “life of exaggerations,” and invest our confidence in those who promise to deliver. This may work out for some, but more often there is the sting of disappointment, a sense of betrayal. As Greil Marcus has written, “America is a trap: its promises and dreams … are too much to live up to and too much to escape.”[ii]

Unattainable promises. Impossible dreams. The lonely crowd grows sullen, resentful, angry, like Nathanael West’s California dreamers in Day of the Locust (1939). Lured by the prospect of a New Eden out West, over the rainbow, they slave and save until they can afford to move to “the land of sunshine and oranges.”

Once there, they discover that sunshine isn’t enough. They get tired of oranges . . . Nothing happens. They don’t know what to do with their time . . . They realize that they’ve been tricked and burn with resentment . . . They have been cheated and betrayed. They have slaved and saved for nothing.[iii]

W. H. Auden described West’s novel as a parable “about a Kingdom of Hell whose ruler is not so much a Father of Lies as a Father of Wishes.”[iv] Either way, it’s a figure we all recognize: the Confidence Man, duping the suckers with his promise to make America great again. “Believe me. Believe me. It’s going to be terrific.”

And what happens when the dreamers tumble back to earth? Most of us muddle on as best we can, but in Stephen Sondheim’s darkly comic musical, Assassins[v], nine embittered and unbalanced Americans find a single target for their anger: the President of the United States. In a carnival of lost souls, a smirking barker (the Confidence Man in disguise!) doles out handguns like cotton candy to a new crop of eager marks. If you keep your goal in sight,” he sings, “you can climb to any height. Everybody’s got the right to their dreams.”

No job? Cupboard bare?

one room, no one there?

Hey, pal, don’t despair-

You wanna shoot a president?

c’mon and shoot a president…

John Wilkes Booth, Leon Czolgosz, Charles Guiteau, Squeaky Fromme, Sara Jane Moore, John Hinckley and a couple more broken dreamers line up to claim a gun as their means of grace and hope of glory.

And all you have to do

Is move your little finger,

Move your little finger and

You can change the world.

The climax takes us to Dallas, where the gang of murderous misfits pressures Lee Harvey Oswald to join their ranks and assuage their shared malady: “a desperate desire to reconcile intolerable feelings of impotence with an inflamed and malignant sense of entitlement.”[vi]

In the finale, all nine assassins come to the front of the stage, singing out with all the confident uplift we expect from our musicals:

Everybody’s got the right to some sunshine!

Not the sun, but maybe one of its beams.

Rich man, poor man, black or white,

Everybody gets a bite,

Everybody’s got the right

to their dreams……

The smiling cast stretches out the last word, “dreams,” for a full twelve seconds as they raise their guns high. The moment the music ends, they all fire at once, a deafening volley, and the stage goes black.

When Assassins premiered in 1990, it was not well received. It seemed too dark and crazy at the time. But when I saw a rare revival this month at Seattle’s ACT Theater, it somehow made perfect sense, so dark and crazy has America become in these latter days.

We all clapped and cheered, of course. It was a fabulous production. The cast was great. It wasn’t all grim. There was plenty of humor. And Sondheim’s songs! But I had tears in my eyes as well. As Jefferson said, “I tremble for my country…”

As the applause went on, I thought of Kierkegaard’s story of a theater which had caught fire backstage as the show was about to begin. The manager grabbed the first actor he found to step through the curtain and warn the audience to evacuate. That actor, alas, was dressed as a clown. “The theater is burning!” he cried. “You must leave immediately!” The audience roared with laughter at the clown’s performance. Such pathos! Such irony! The more he shouted and pleaded, the more they laughed, until they were all consumed by the flames.

[i] Herman Melville, The Confidence Man: His Masquerade in Pierre, Israel Potter, The Piazza Tales, The Confidence-Man, Uncollected Prose, Billy Budd, Sailor (New York: Library of America, 1984), 452

[ii] Greil Marcus, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘N’ Roll Music (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1975), 22

[iii] Nathanael West, Day of the Locust (from my personal transcription in a 1968 commonplace journal, original page unknown)

[iv] Wikipedia reference: Barnard, Rita. “‘When You Wish Upon a Star’: Fantasy, Experience, and Mass Culture in Nathanael West” American Literature, Vol. 66, No. 2 (June 1994), pgs. 325-51

[v] 1990, music & lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, book by John Weidman

[vi] John Weidman interview, quoted in Misha Berson’s Seattle Times review, March 9, 2016

Pingback: Is the American Dream a Con Game? — The religious imagineer | Unchain the tree

Itâs a good one honey! Already shared!

good idea

Pingback: Summoning the Sanity to Scream | The religious imagineer

Pingback: “Not too late to seek a newer world” | The religious imagineer

Thank you for writing tthis