“The image can be worn down to the point that it is almost invisible, it can be plunged into darkness and disfigured, it can be clear and beautiful, but it does not cease to be.”

— Saint Augustine

Four hundred and fifty years ago, Paolo Veronese painted his controversial version of the Last Supper for a Venetian monastery. It was hung in the refectory, where the monks could contemplate the sacredness of every meal in the artist’s image of the first eucharist. But when the censors of the Venetian Inquisition had a look, they were shocked to find the holy scene crowded with “buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities.”[i] Although Veronese argued that the invented characters were needed to fill the immense canvas (42 feet wide), and that Christ was safely separated from the more unseemly guests within the central arch, the Inquisitors were not persuaded. The disorderly and irreverent scene was antithetical to the purpose of religious art. It would produce distraction, not devotion.

Veronese was given three months to change the painting. Instead, he gave it a new title: Christ in the House of Levi. As Luke’s gospel tells us, Jesus was known for eating with “publicans and sinners,” so the switch of subjects from Last Supper to Levi’s party made the scandalous scene properly scriptural. The artist was off the hook, and the Inquisitors dropped their complaint.

At the Opening Ceremonies of the Paris Olympics, a similar controversy arose when a brief tableau of a pagan feast was taken to be a mocking parody of the Last Supper. The diverse figures standing behind the raised runway of a fashion show, grouped on either side of a central figure with a silver “halo”, evoked for some the well-known iconography of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper. But instead of a male Christ, the central figure was a woman, flanked not by pious apostles but dancing drag queens.

The French Bishops’ Conference slammed the tableau as a “mockery and derision of Christianity.” Mike Johnson, the right-wing Evangelical Speaker of the House in the United States Congress, decreed the performance “shocking and insulting to Christian people around the world.” The event’s artistic director, Thomas Jolly, denied the Last Supper allusion. The scene was a pagan feast on Mount Olympus. The Olympics! Get it? The blue man sitting on a pile of fruit in the foreground depicted Dionysos, Greek god of wine and fertility. There was no intention to “be subversive or shock people or mock people,” Jolly said. [ii]

The true inspiration for the tableau, suggested its defenders, was not Leonardo’s masterpiece, but a seventeenth-century painting by Dutch artist Jan van Bijlert, The Feast of the Gods. There is a table with a central figure behind it, but it’s Apollo. And no one would mistake all those Olympian carousers for Christian saints. However, I do wonder. Was Bijlert’s table itself inspired by Leonardo’s, making his own pagan tableau a sly remix of the Last Supper?

Whatever the intention of the Olympic organizers, the negative outrage poses a critical question. What is the table fellowship of Jesus all about? Is it not an indelible image of divine welcome? If so-called “Christians” profess to be shocked at the presence of misfits and outcasts at God’s feast, are not they the true blasphemers against the Love Supreme?

The Last Supper has long been one of the most recycled images of Christian iconography. As a widely recognizable motif of human solidarity and divine gift, it is a visual code for what everyone longs to hear: Come in. Sit down. You are welcome here.

Van Gogh’s The Potato Eaters, manifesting the eucharistic dimension of every table, however humble, was inspired by the Last Supper paintings of Tintoretto (1518-1594) and Charles de Groux (1825-1870).

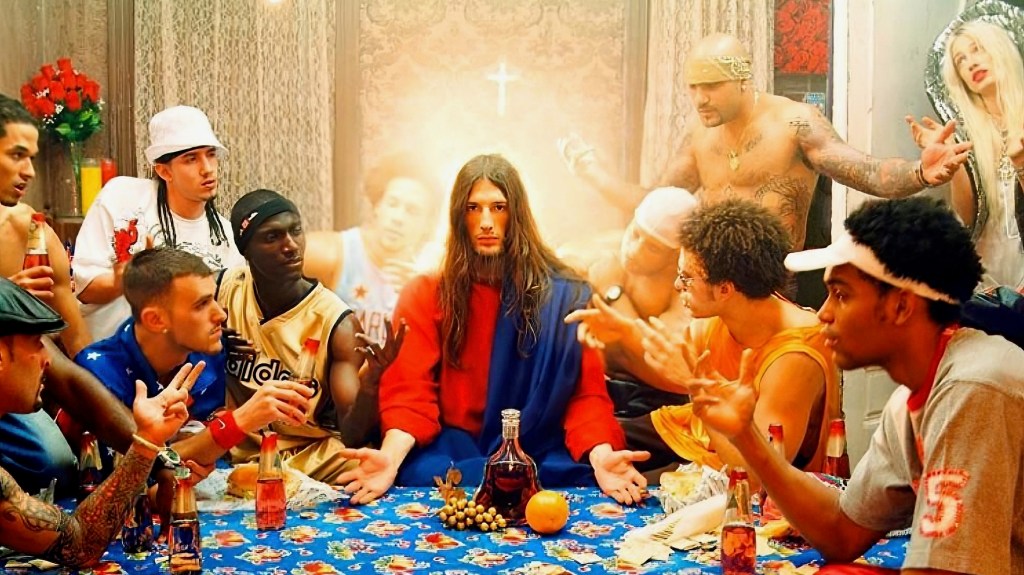

In recent decades, photographers have invited some surprising guests to the table, often with a subversive image of Christ in the middle. Nathalie Dietschy’s extensively illustrated book, The Figure of Christ in Contemporary Photography, provides a wide variety of examples, such as David LaChapelle’s Last Supper from his 2003 series, Jesus is My Homeboy. “If Jesus was alive today,” says the artist, “this is who he would be with. He was with the outcasts, the apostle. What would the apostles look like today? The apostles were not the aristocracy, they were not the well to do, they were not the popular people, they were sort of the dreamers, the misfits.” [iii]

Raised a Roman Catholic, LaChapelle wanted to “rescue” Jesus from limiting stereotypes. He described his Homeboy series as “a personal attempt to say [to fundamentalists]: ‘you have ruined so much, but you are not going to take this.’” [iv]

Some of Dietschy’s other photographic examples of the Last Supper genre are Marcos López’s Roast Meat in Mendiolaza, with the central figure at the table stabbing a hunk of meat with a knife at an outdoor barbecue in Argentina … Rauf Mamedov of Azerbaijan having men with Down’s Syndrome reproduce the gestures of Leonardo’s apostles as they ask, “Is it I, Lord?” … Faisal Abdu’Allah, a Jamaican-born American, inserting his own blackness into the story with disciples of color, both men and women, dressed as rap artists or veiled and robed in traditional Muslim dress … New Zealander Greg Semu exploring the tensions between indigenous and colonial cultures in The Last Cannibal Supper … ‘Cause Tomorrow We Become Christians, where the artist himself, as the Christ figure, presides over a table laden with cooked flesh and a human skull, as his disciples, anxious about transitioning identity, look ill at ease … and a couple of Chinese artists filling the table with Red Army soldiers, or Chinese schoolgirls with identical faces.

Such revisions of sacred iconography can be challenging, bewildering, or even disturbing. And any erosion of the “aura” of religious symbols, especially in this secular age where technology’s infinite reproducibility of images has revoked all the Christian copyrights, is a subject worth thoughtful consideration. But the persistence of sacred tropes, even when trivialized or misappropriated, is itself a testimony to their power. The logic of the Incarnation means that the divine can become indistinguishable from the human, erasing the boundary between sacred and profane.

The Last Supper by Swedish artist Brigitte Niedermair in 2005 first appeared in women’s magazines as an ad for a contemporary clothing brand. Leonardo’s postures and gestures are explicitly performed, strikingly, by women. There is one enigmatic young man, with his bare torso turned away from the viewer. He seems bent in sorrow, perhaps foreshadowing the Pietà.

The image’s feminine casting created a stir, unnerving the patriarchal segments of the Church. It was condemned, even banned, in some Catholic countries. But others expressed understandable reservations concerning the slick commercialization of a sacred image in order to sell expensive clothing. The ad agency seemed taken aback by the objections. “We wanted to convey a sort of spirituality through this image,” they said. It was “an homage to art and to women.” [v]

A pair of Last Suppers, each set in the Middle East, demonstrates how critical context is to the reception of art. The current violence in Gaza endows them with a fresh layer of tragic intensity. Put next to each other in 2024, they touch a raw nerve. If only humanity could heed the divine commandment spoken at the original table: Love one another.

Adi Nes’s untitled photograph from his 1999 Soldiers series, by arranging fourteen men on one side of a table, invokes Leonardo’s iconography. The soldiers are conversing in small groups, but the man in the Christ position appears lost in his own thoughts. Nes, who himself spent three years in the Israeli Defense Force, has said that “all of them are Jesus, all of them are Judas.” All equally at risk, all equally in need of forgiveness and compassion. “I hope this isn’t their last supper,” he says.[vi]

A similar nod to Leonardo by Indian artist Vivek Vilasini, Last Supper—Gaza (2007), fills the table with Palestinian women, whose anxious and fearful eyes show the distress of living under constant threat. Is it I, Lord? Is it I who will betray? Is it I who will run away? Is it I who will die?

Yo Mama’s Last Supper (1996), by Jamaican-American Renee Cox, is one of the most controversial versions. It employs Leonardo’s canonical table image, but the apostles themselves, except for a white male as Judas, are black or mixed-race and not exclusively male. They all wear traditional biblical dress, except for Jesus, who is naked. Played by the artist herself, the Christ figure spreads her arms wide like the presider at the eucharist. A white shroud is artfully draped over her arms in the manner of crosses decorated at Easter.

There is no mockery in the image. It shares the solemn stillness of traditional religious painting. But in showing Jesus as a “triply marginalized figure due to race, gender and physicality,”[vii] the image aroused heated attacks. When it was first exhibited in New York in early 2001, Mayor Rudy Giuliani called it “disgusting, outrageous and anti-catholic.” William Donohue, President of the Catholic League, said that “to vulgarize Christ in this manner is unconscionable.” However, in a debate with Cox at the Brooklyn Museum, he admitted that “there would be no problem if you had kept your clothes on.” [viii]

Cox’s response to her critics was not apologetic. “An African-American woman putting herself in a position of empowerment seems to be a national threat,” she said. “I’m not taking a backseat. I’m going to sit at the head of the table.” As for the nakedness, she insisted it was not her intent to eroticize a sacred scene. “I chose to play the Christ figure in the nude because it represents a certain sense of purity. I come to the table with nothing to hide.”[ix]

The Last Supper by Swedish artist Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin is perhaps the closest parallel to the Olympics’ notorious tableau. Modeled after a 16th-century painting by Juan de Juanes, it populates the table with transvestite disciples and a Jesus of uncertain gender, wearing high heels and holding up a makeup sponge instead of the sacred Host. Created by a lesbian artist raised in the Church, it was part of a photographic series, Ecce Homo, featuring biblical scenes with LGBTQ models.

The Ecce Homo photographs, unsurprisingly, created a furor in the last years of the 20th century. The fact that they were exhibited in churches rather than museums served to fuel the outrage. The propriety of untraditional visuals in sacred space is a particularly fraught question. Placing Wallin’s Last Supper above the altar of a Zurich church prompted vandalism and bomb threats.

While I do wonder whether the cognitive dissonance of Wallin’s image competing for attention with the actual sacrament would deepen or disrupt a worshipper’s ocular piety, the radical inclusiveness conveyed by Ecce Homo was a blessing to many. “Thank you for this wonderful representation of the life and deeds of Jesus,” someone wrote in the Visitors’ book at the Zurich exhibition. “Through it, I can now identify with them, today, in the 21st century. I pray for all those who are rejected by our society: ‘The Last shall be the first!’” [x]

That’s really what it’s all about, isn’t it? Who belongs at the table? Who is welcome at the table? The Opening Ceremonies controversy was not about Leonardo vs. Jan van Bijlert, Mount Olympus vs. the Upper Room, pagan vs. Christian, Jesus vs. Apollo. It was about who gets to sit at Love’s table. And for those who think that the Last Supper represents anything less than that: You are in for a surprise.

Lcve bade me welcome, yet my soul drew back

Guilty of dust and sin.

But quick-ey’d Love, obeserving me grow slack

From my first entrance in,

Drew nearer to me, sweetly questioning,

If I lacked anything.

A guest, I answer’d, worthy to be here:

Love said, You shall be he.

I, the unkind, ungrateful? Ah my dear,

I cannot look on thee.

Love took my hand, and smiling did reply,

Who made the eyes but I?

Truth Lord, but I have marr’d them: let my shame

Go where it doth deserve.

And know you not, says Love, who bore the blame?

My dear, then I will serve.

You must sit down, says Love, and taste my meat:

So I did sit and eat.

— George Herbert, Love (III)

[i] The Inquisition transcript: https://web.archive.org/web/20090929022528/http://www.efn.org/~acd/Veronese.html

[ii] Yan Zhuang, “An Olympics Scene Draws Scorn. Did It Really Parody the Last Supper?”, New York Times, July 28, 2024. I can’t help noting that any such outrage from the Christian right in America rings hollow. They have lost the credibility to speak on behalf of the friends of God. Their shameful worship of a depraved, and hate-filled sexual predator, convicted fraudster and would-be dictator as an instrument of divine will has brought more disgrace to Christianity than a thousand pagan parodies.

[iii] Nathalie Dietschy, The Figure of Christ in Contemporary Photography (London: Reaktion Books, Ltd.: 2020), 123.

[iv] Ibid., 128.

[v] Ibid., 167.

[vi] Ibid., 110.

[vii] Katharine Wilkinson, The Last Will Become First: Liberation of Race, Gender and Sexuality in Renee Cox’s “Yo Mama’s Last Supper”, quoted inDietschy, 254.

[viii] Dietschy, 256.

[ix] Ibid., 256, 257.

[x] Ibid., 261.

Thank you! Love reigns supreme.

Indeed it does. Thank you for reading.

I did not realize the impact of the Last Supper among artists. Your tour of the images is startling. Christ continues to make keepers of dogma (as well as me) uncomfortable.

As always Jim, I am impressed with your scholarship. On this one, however, I must disagree. This “show” was designed to humiliate and denigrate Christians. Of course they hate us because “hate” is what these people do. As Christians our Lord has told us not to hate back. So we don’t. But I will not embrace them.

And by the way: Happy Birthday! We made it! The big 80.

Hmm. I’m curious. I do not feel hated by this art. I may be uncomfortable, but then I wonder what that is about me rather than make assumptions of hatefulness on their part. So “our Lord has told not to hate back”, but not embracing them sounds like rejecting them, and is that not a lack in kindness? Absence of hate, or suppression hate, but not embracing; it’s not clear to me that they are much more different than level of intensity.

I very much enjoyed this comprehensive tour of representations of the Last Supper, and the degree to which it has always been provocative. As it should be. I suppose I might make a small complaint that the Simpson’s last supper was included as a pop culture reference, but not the finale of Battlestar Galactica? That was the pop culture tour de force when I was coming into adulthood.https://images1.fanpop.com/images/photos/2100000/Battlestar-Last-Supper-battlestar-galactica-2158797-1024-392.jpg

One small quibble with your essay Jim: “Love’s table”? I don’t think I’m comfortable with abstracting the flesh and blood Jesus into the shallowness of “Love” capital L. It’s Jesus’ table.

We sing hymns, not John Lennon songs. God is love, which does not mean Love is god. The latter is vague sentimentality, the former is the concrete declaration that in the broken body of Christ God was reconciling all of us back to our Creator. Love did not die on that old rugged cross. Love was shown on that old rugged cross, the love of a savior who lay down his life for his friends … and even his enemies.

Thank for your thoughtful reading. I was using “Love” in the spirit of George Herbert, who was no sentimentalist. As you point out, I was not aiming at Christological or soteriological precision, but I hope my basic point remained biblical. As the Spirit and the Bride say, “Y’all come.”

Once again, “thank you” Jim. I think you summed up the perspectives very well. In my opinion the public response by Christians to the Olympics scene are exceedingly more outrageous than any intentional or unintentional parodying of the last supper by Thomas Jolly. Why would any non-follower of Jesus want to join these vociferous and hateful critics if they represent what following Jesus is about? Jesus had something to say about gnat straining.

It seems judgmental to say if a believer was offended at the Olympics scene that they are “so-called Christians or blasphemers against the Love Supreme”. I think such descriptions amongst members of Christ’s Body are uncharitable and no different from the venom spewed along the political divide. The Body of Christ should be known by our great love of one another not identical to the hatred amongst the worldly.

Thanks Jim, Clear, incisive, insightful. And the best commentnisnhiddennin a footnote (re the “depraved, and hate-filled sexual predator, convicted fraudster and would-be dictator”).