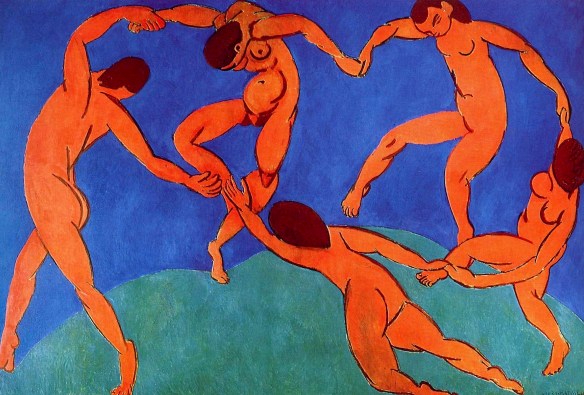

spectra III, an installation by Ryoji Ikeda at Venice Biennale 2019: “a blinding excess, rendering the space itself almost invisible.” (Photo by Jim Friedrich)

Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart describes atheism as “a fundamentally irrational view of reality, which can be sustained only by a tragic absence of curiosity or a fervently resolute will to believe the absurd. . . [T]rue philosophical atheism,” he says, “must be regarded as a superstition, often nurtured by an infantile wish to live in a world proportionate to one’s own hopes or conceptual limitations.”[1]

For the people of Advent, “a world proportionate to our own hopes” is too mean a thing. The mystery of the world and the destiny of mortals are too deep, too immense, to be contained by language or thought. They exceed everything we can ask or imagine. They explode our limited notions of what is real and what is possible.

Not for the people of Advent that “tragic absence of curiosity” so common in a complacent secular culture too busy amusing itself to consider the deepest questions of human existence. Advent people want to know who we are, why we’re here, where we’re going, and how long we’ve got. Most of all, we want to know whether we matter, and whether we are loved.

But are such questions answerable? Our thoughts and concepts only take us so far, like a compass pointing north. “North” is a pretty useful guide––until you reach the North Pole, where the very concept of north loses its meaning. Just so, the closer our thoughts take us toward the divine center, the less they are able to tell us.

At the end of The Divine Comedy, when Dante beholds the presence of God unveiled at last, words fail him:

What then I saw is more than tongue can say.

Our human speech is dark before the vision.

The ravished memory swoons and falls away. [2]

The mystery we call God is always beyond us. Beyond our grasp, beyond our language, beyond our sight. The mystics and great spiritual teachers sometime use the word darkness to convey their experience in close encounters with the divine.

But what they call the darkness of God is not so much a matter of cognitive deprivation, where divinity simply hides its incommunicable essence from finite minds and hearts unprepared to receive it. No, they say, the darkness of God is not deprivation, but saturation. It is not an absence of light, but an excess of glory, that makes our eyes become so dim to divine presence.

It sounds paradoxical––to be blinded by the light of God––but only paradox has the wings to carry us beyond the prosaic into the heavenly place where all contraries are reconciled. The metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century, like John Donne and George Herbert, reveled in such holy paradox. Henry Vaughan, for example, wrote that

There is in God (some say)

A deep, but dazzling darkness; As men here

Say it is late and dusky, because they

See not all clear;

O for that night! where I in him

Might live invisible and dim. [3]

Was Vaughan just playing with words, or was he on to something? At this year’s Venice Biennale, I had a very literal experience of being blinded by the light in an installation by Japanese artist Ryoji Ikeda. What happened to me there is perfectly described by the text posted at the entrance:

“spectra III” consists of a corridor of bright fluorescent tubes. This all-encompassing installation bathes the visitor in light so bright it is difficult to see. Akin to a blizzard of data, the experience short-circuits our ability to process what we are seeing, and results paradoxically in a sensory wipe-out. Ryoji Ikeda sees this state of overload as opening the door to an experience of the sublime––a landscape of light too complex to comprehend. The installation functions in parallel to the experience of total darkness, yet inverts this experience. We are similarly disoriented but instead of an absence of light by which to see, there is a blinding excess, rendering the space itself almost invisible.

That’s exactly what happened to me in that corridor. I had never before experienced such a literal analogue to the blinding luminosity described by the mystics. It was truly a “deep and dazzling darkness.” Almost painful, to tell the truth. Certainly too much for my mortal eyes to take in.

It may seem paradoxical to speak of the darkness of God at the beginning of Advent, when we light candles against the lengthening nights, and pray for the “grace to cast away the works of darkness, and put on the armor of light,” as if the soul’s journey were a straightforward itinerary from deepest midnight to eternal day. But as the mystics and poets insist, God-talk must be paradoxical to be useful and true. “God draws straight with crooked lines,” they say. God is the burning bush and the cloud of unknowing. You can’t have one without the other.

“God goes belonging to every riven thing,” says the poet Christian Wiman.

He’s made

the things that bring him near,

made the mind that makes him go.

A part of what man knows,

apart from what man knows,

God goes belonging to every riven thing he’s made. [4]

God is “apart” from what we know, transcendent to our empirical minds––minds which themselves keep God at a distance through our forgetfulness, idolatry, and egoism. And yet God wants to be near, wants to be known. God “goes belonging” to every riven thing: the broken, the wounded, the lost. God goes belonging to us all. And in so doing God’s own self is riven into the contraries of darkness and light, near and far, infinite and incarnate, present and absent, visible and invisible.

Advent’s great themes are seeking and waiting, hoping and expecting, longing and desiring. We go looking for God, searching for signs of God’s appearing.

Sometimes, in our search, we seem only to find darkness, silence, or absence, because we are looking in the wrong place, or in the wrong way. Or we are simply looking for the wrong thing, and need to be denied the fulfillment of inadequate expectations because they are too small or ill-proportioned to fit the immeasurable desire of God. For example, we might expect a well-armed conqueror instead of a servant and sufferer. Or we might expect an irresistible righter of wrongs instead of a helpless refugee child lying in a manger––or, these days, lying in a cage.

We were made to be in union with God, and our desire for that union is the deepest truth within us. We feel incomplete and unfinished without it. But our desire often goes astray and misses its mark, attaching itself to something well short of God. If our desire gets stuck on anything less than God, we will waste our lives worshipping the wrong thing,

In a 1967 film by Jean-Luc Godard, a well-dressed couple in a sporty convertible pick up a hitchhiker who tells them he is God. They are very excited to meet him. “Can you do miracles?” asks the man, “Can you make me richer?” His wife adds her own requests: “Can you make me young and beautiful?” And “God” replies, “Really? Is that all you want? I don’t do miracles for idiots like you!” [5]

One of the reasons that Christians worship together and pray together and learn together is to train our desire, so we don’t wait for the wrong thing, or hope for the wrong thing, or love the wrong thing, but always keep our eyes on the prize. Admittedly, God isn’t all that easy, and God is certainly not tame. As Emily Dickinson said, the divine “invites––appalls––endows–– / Flits––glimmers––proves––dissolves–– / Returns––suggests––convicts––enchants / Then––flings in Paradise––“[6]

Still, we are not deterred. Still, we cry Maranatha! Come, Lord, come! At least some of us do. There are those who don’t, for they think God is too invisible or too impossible to take into account. But isn’t that the point? Nothing we can see can save us. Nothing that is possible can rescue us. Paradox, paradox…

The human condition, suspended somewhere between the finite and the infinite, is a complicated puzzle, a question with no clear answer. As for the times we live in, Humphrey Bogart summed it up nicely in the film Beat the Devil:

“What’ve you got to worry about? We’re only adrift on an open sea with a drunken captain and an engine that’s likely to explode any moment.”

Is God coming to save us? As we know, that question is often answered by delay. Or worse, silence. We peer toward an uncertain horizon, looking for the One who comes with clouds descending, or at least for the comforting glow of dawn. But the horizon is hidden by what Nicholas of Cusa, a fifteenth-century German theologian, called “that obscuring haze of impossibility.”

And the darker and more impossible that obscuring haze of impossibility is known to be, the more truly the Necessity shines forth and the less veiledly it draws near and is present… I give You thanks, my God, because… You have shown me that You cannot be seen elsewhere than where impossibility appears and faces me.” [7]

I love Nicholas’ name for God: “the Necessity.” And I love his image of divine revelation as the moment when “impossibility appears and faces me.” The impossibility, the beyondness of God––beyond all knowing, beyond all saying, beyond all seeing––abolishes our limiting notions of what is possible, making a way where there is no way. O for that Night! where I in him may live invisible and dim.

All this talk of the darkness of God, the hiddenness of God, the elusiveness of God, may seem to run counter to the more affirmative language we usually employ in the liturgy as well as in the conversations we have together as people of faith.

We call ourselves God’s friends. We experience God’s closeness in times of gratitude and times of need. We see God’s hand in works of justice and mercy, and feel God’s Spirit in the reconciling and sacrificial love of human relationships. We meet God in Scripture, in community, in nature, and in beauty. We meet God in the poor, the vulnerable, and the dispossessed.

But sometimes God is hard to find or hard to perceive, and in those times we must speak the Advent language of not-exactly, not-here, and not-yet. That’s why the gospel for the First Sunday of Advent always has Jesus warning us to be on the ready. “Out with the old and in with the new! The world of the past is falling down, falling down. Whatever is going to happen next, expect the unexpected.”

Faced with the collapse of old ways and familiar certainties, where shall we look for God in the brave new world?

There’s a story about a man who dreams he is wandering among the labyrinthine stacks of the immense Clementine library in Prague. A librarian wearing dark glasses approaches him to ask, “What are you looking for?”

“I am looking for God,” he says.

“Ah,” said the librarian. “God is one of the letters on one of the pages of one of the four hundred thousand volumes in the Clementine Library. My parents and my parents’ parents searched for that letter. I myself have gone blind searching for it.” [8]

We’re all searching for that word, that moment, that appearing. It may bring the holy blindness of the mystics, or it may bathe you in the gentler glow of illumination. God only knows. Either way, you will not be left comfortless. God goes belonging to every riven heart.

In this season of Advent, I invite you to contemplate the paradoxical depths of the divine, to immerse yourselves in periods of wordless prayer within God’s luminous darkness. Set aside your concepts and your dogmas, and wait in the stillness of unknowing for the Word to speak. The God who is beyond all language and beyond all knowing wants to disclose Godself to us, wants to give Godself to us. That is the divine desire––the siege of God at the gates of our heart.

Stay awake. Pray for grace. Do not lose faith. As Jackson Browne exhorts us in his great Advent song, “For a Dancer”:

Keep a fire burning in your eye,

and pay attention to the open sky––

you never know what will be coming down.

One last thing.

Paul Celan was a Romanian Jewish poet who survived the Holocaust. It has been said that his difficult poetry “is not willed obscurity” but “comes out of lived experience and is ‘born dark.’” [9] Celan knew the darkness of hell, but he also knew another kind of darkness, a darkness which paradoxically contains the seeds of light.

His poem called “The Narrowing” [10] includes a stanza of four short lines that express the spirit of Advent people––the people who sit in darkness without losing faith in the light to come. In just 16 words, the verb “came” is spoken 5 times, like an incantation in response to our beseeching prayer, “O come, O come, Emmanuel.” What comes, comes in the dark, but it brings a desire for light:

Came, came.

Came a word, came,

came through the night,

wanted to glow, wanted to glow.

This post was delivered as a sermon on the First Sunday of Advent, 2019, at St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, Bainbridge Island, WA 98110.

For links to other Advent resources: How Long? Not Long!––The Advent Collection

[1] David Bentley Hart, The Experience of God: Being, Consciousness, Bliss (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 16.

[2] Dante Alighieri, Paradiso xxxiii: 55, trans. John Ciardi.

[3] Henry Vaughan, “The Night,” cited in Peter O’Leary, Thick and Dazzling Darkness: Religious Poetry in a Secular Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 85.

[4] Christian Wiman, “Every Riven Thing,” in Every Riven Thing (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2011).

[5] Jean-Luc Godard, Weekend (1967).

[6] Emily Dickinson, “The Love a Life can show Below.”

[7] Cited in Didier Maleuvre, The Horizon: A History of Our Infinite Longing (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 143.

[8] From “The Secret Miracle,” a story by Jorge Luis Borges.

[9] From Shoshana Olidort’s Chicago Tribune review of Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry of Paul Celan, cited on the Poetry Foundation website: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/paul-celan

[10] The original German title is “Engführung.”