“[A] contemplative politics will be one that is capable (as seems so unthinkable in public life at the moment) of recognizing and naming our own failure, the hurt done as well as received, and the perpetual slippage toward violence.”

— Rowan Williams [i]

“It is not easy / To believe in unknowable justice / Or pray in the name of a love / Whose name one’s forgotten: / … spare / Us in the youngest day when all are / Shaken awake, facts are facts, / (And I shall know exactly what happened / Today between noon and three) …”

— W. H. Auden [ii]

After the unspeakable savagery of October 7, how can anyone think? The violence is too visceral, the wound too deep. Dispassionate discourse on causes and solutions risks sounding cold and inhuman amid our “tears of rage, tears of grief.” Susan Sontag tried it after 9/11: “Let’s by all means grieve together,” she wrote in The New Yorker. “But let’s not be stupid together. A few shreds of historical awareness might help us understand what’s happened.” [iii] Sontag’s cool detachment was widely criticized for being tone deaf to the moment. I will try not to be; forgive me if I fail. I have wept and prayed over this violence, but here I want to reach toward lucidity. And hope.

I’m admittedly no expert on the complex region and its conflicts. I was in the “Holy Land” for 40 days and 40 nights in 1989 and for 3 weeks in 1991, primarily on pilgrimage. But I spent some memorable time with Palestinians, and had an illuminating day with human rights advocates in Gaza—it looked like a war zone even then, with overturned trucks and ruined buildings. The Anglican Al Ahli Arab Hospital had performed 79 surgeries in a single day that month. But the day I visited the number was only 4: two for gunshots, two for beatings. I still can’t imagine the effect of living with so much death and violence year after year.

My only personal intifada moment came when I was videotaping a burning tire in an empty square in Ramallah. Two armed soldiers appeared out of nowhere, demanding to see what I’d shot, in case I’d caught the protesters on tape. Fortunately, my footage only showed the tire. I did not want to be the cause of anyone’s arrest.

President Biden called Hamas’ sadistic violence “an act of sheer evil.” Only the heartless could disagree. The question now is: What do we—Israel, the United States, the Arab states, the whole human race—do about it? South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham said, “Level the place” (meaning Gaza). He might as well have said, “Let’s be stupid together.” There are two million inhabitants in Gaza (half of them are children), and the indiscriminate mass slaughter of innocent and guilty alike would not eliminate terror, but only metastasize it. For terrorists, the blood of the “martyrs” is the seed of future violence.

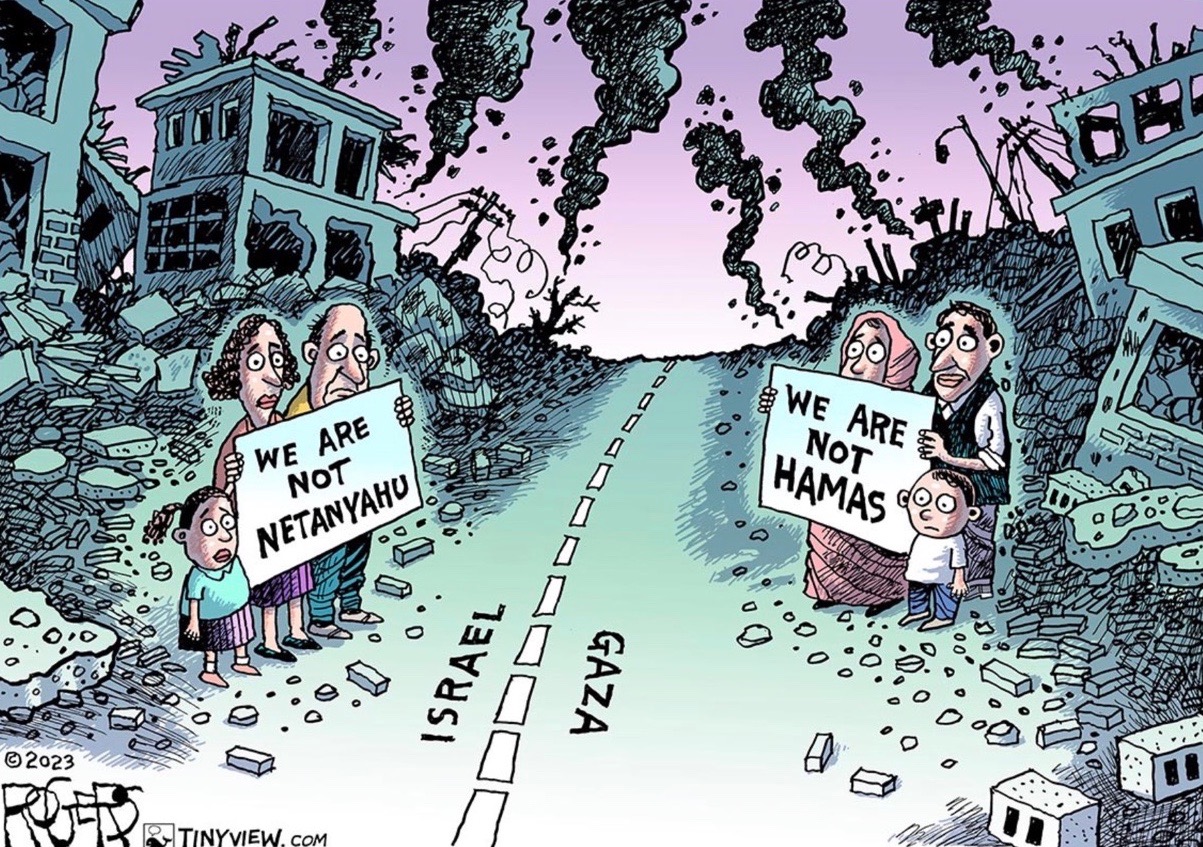

Many of us think of terrorism as an interruption of a normally peaceful world. Terrorists see conflict as a perpetual condition, and insist that their violence, whatever its methods and goals, is in response to something they didn’t start. For a very long time, the Middle East has suffered a seemingly endless cycle of violence and vengeance. To call the attack of October 7 “unprovoked” or “out of the blue” is a case of willful ignorance. It is in fact a particularly monstrous continuation of the cycle. Recognizing historical context in no way justifies the sickening barbarism of specific cruelties, but if we want to find a way forward we need to do better than just point fingers. As the Bible warns, “If we say we have no sin we deceive ourselves” (I John 1:8).

The human rights consensus is that Netanyahu’s years-long blockade of Gaza has been a form of apartheid, an attempt to confine Hamas, whose declared aim is the destruction of Israel, within the Gaza Strip’s narrow boundaries. Tareq Baconi, president of the board of a Palestinian think-tank, believes that October 7 has undermined any illusions about the sustainability of that approach:

“The scale of the offensive and its success, from Hamas’s perspective, mean that we’re actually in a new paradigm, in which Hamas’s attacks are not restricted to renegotiating a new reality in the Gaza Strip, but, rather, are capable of fundamentally undermining Israel’s belief that it can maintain a regime of apartheid against Palestinians, interminably, with no cost to its population.” [iv]

Ruth Ben-Ghiat, an expert on authoritarianism, sees the malign ineptness of Netanyahu’s “strongman” regime as playing its own part in the crisis by oppressing Palestinians and weakening Israeli consensus. Many Israelis wish him gone. The Prime Minister, she writes,

“did not seem to care that empowering his far-right extremist partners (his Minister of National Security, Itamar Ben-Givr, has been convicted of supporting terrorism) to try and realize their fantasies of a Jewish ethno-state and West Bank annexation could have dangerous consequences for the nation.

“With a two-state solution off the table for Netanyahu, repression of Palestinian human and political rights has been the default solution, along with giving Palestinians some limited economic benefits. That this was not tenable did not interest him. That typical authoritarian rigidity and hubris is why former Shin Bet head Ami Ayalon told Le Figaro that Netanyahu’s government bears ‘a large part of the responsibility’ for creating a climate that Hamas judged propitious for an attack.” [v]

Israel, of course, is not alone in its need to reassess the policies and paradigms of power for the sake of justice and lasting peace. As former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams says, we all need to come to terms with “our own failure, the hurt done as well as received, and the perpetual slippage toward violence.” Or as Auden put it, we need to be “shaken awake” and forced to face facts. It is simply not possible to unremember “what happened between noon and three” (the Crucifixion) and what will happen again and again until we choose a better way.

During last week’s terror, the latest issue of the New York Review of Books arrived in my mailbox. The first article I saw, Suzy Hansen’s discussion of writer Phil Klay, opened with a paragraph that seemed made for the moment:

“The act of killing people was once taken so seriously, Phil Klay writes in Uncertain Ground: Citizenship in an Age of Endless, Invisible War, that after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, a Penitential Ordinance was imposed on Norman knights: ‘Anyone who knows that he killed a man in the great battle must do penance for one year for each man that he killed.’ Klay, a forty-year-old veteran of the war in Iraq, considers such rituals beneficial not only for the psychological health of soldiers but also for their communities, because after a war the traumatized perpetrators ‘must reconstruct a view of faith, society, and ethics that will not merely collapse into the emptiness of the evil they have faced.’ A nation left flailing in the emptiness of evil becomes one in which that evil never ends.”

Whether we are Israelis, Palestinians, Ukrainians, Russians, or citizens of the American empire, we are implicated, directly or by proxy, in perpetual global conflict, where the only true winner is the technology of violence—along with the few who profit by it. In Hansen’s words, the rest of us are “prisoners of that global technological warship that is always on the move.”

How do we say no? How do we jump that warship? As Hansen reminds us,

“The war on terror devastated entire countries, caused the deaths of millions of people, and turned tens of millions into refugees; countless more people were imprisoned, maimed, tortured, or impoverished.”

We might add to that distressing number the 30,177 American soldiers and veterans of the war on terror who have committed suicide over the last 20 years. A soldier quoted in Klay’s Uncertain Ground suggests a cause for such despair when he wonders, “Have I done an evil thing?” [vi]

Are the policy-makers and war-makers similarly troubled? Do they ever have PTSD after the harm they do? Auden’s “Epitaph on a Tyrant” is doubtful on this point. The poem’s last line exemplifies the fatal disconnect between the performative emotions of the powerful and the suffering they either cause or ignore. Whether or not the tyrant weeps, the children go on dying.

Perfection, of a kind, was what he was after,

And the poetry he invented was easy to understand;

He knew human folly like the back of his hand,

And was greatly interested in armies and fleets;

When he laughed, respectable senators burst with laughter,

And when he cried the little children died in the streets. [vii]

In recent days, thousands of bombs have been dropped on Gaza, which is under a state of siege. The severing of access to food, water and electricity is in itself a death sentence for many, especially those in hospitals. Al Ahli Arab Hospital, where I photographed 12-year-old Sabir in 1989, was struck by a bomb as I was writing this. It has been sheltering people displaced by the war, and the number of dead is thought to be around 500.

Israeli forces are preparing for a bloody invasion of Gaza, but there is a glimmer of hope in recent diplomatic moves to secure humanitarian aid and evacuation of civilians, and to win release for hostages. Even so, many more innocents are going to die, along with countless combatants. This war will win nothing but more rage and more tears.

Pete Seeger once said, “We must learn to forget revenge.” In a New York Times op-ed last Sunday, “What Does Destroying Gaza Solve?”, Nicholas Kristof told of meeting “a woman named Sumud Abu-Ajwa, whose home had been damaged by bombing in 2014 and whose husband had been injured and whose children were hungry.

“Do you want Israeli mothers to suffer like you?” I asked.

“Of course not,” she answered. “I hope God won’t let anyone taste our suffering.” [viii]

— Rowan Williams

Nothing but evil can come from feasting on revenge. Any further slaughter of the innocents will only produce more rage, more retaliation. So what to do? In the short term, work to free the hostages and aid the desperate. For the long term, practice justice, renounce oppression, and work for peace. Make space for one another. Trade tribalism for human solidarity. See God in every face.

As we approach All Hallows (November 1), the creative folly of saints comes to mind. Keeping their eyes on the prize, they refused the well-worn schemes of a death-haunted world in favor of practices shaped by divine love: self-forgetting and self-offering. Take St. Francis, for example, who went to Palestine during the Crusades. Making his way to the war zone, he crossed the battle line, unarmed, to seek out the Muslim leader, Malek el-Kamil. The sultan received him courteously, they had a friendly conversation about God and, it is said, Francis took time to say prayers in a mosque. “God is everywhere,” he told the sultan.

I wish I could say that the example of St. Francis so moved the hearts of the adversaries that they laid down their swords and shields to live happily ever after. Alas, not so. But we still treasure that story for the day when the world might actually be ready for such holy wisdom.

During World War II, when the Christian intellectual and activist Simone Weil was working in the London office of the French Resistance, she proposed a plan to parachute hundreds of white-uniformed nurses onto battlefields, not only to tend to the wounded but also to provide an image of self-sacrificial goodness in the midst of cruelty and violence. She herself wanted to be in the first wave of this non-violent invasion. In submitting her plan to the Free French authorities, she made a visionary argument:

“There could be no better symbol of our inspiration than the corps of women suggested here. The mere persistence of a few humane services in the very center of the battle, the climax of inhumanity, would be a signal defiance of the inhumanity which the enemy has chosen for himself and which he compels us also to practice … A small group of women exerting day after day a courage of this kind would be a spectacle so new, so significant, and charged with such obvious meaning, that it would strike the imagination more than any of Hitler’s conceptions have done.” [ix]

Charles de Gaulle thought her quite mad, and her plan of course went nowhere. What would happen if we tried such a thing in Gaza? God only knows.

Yes, I can imagine what you’re thinking. But if I haven’t lost you by now, let me offer one final example of holy folly.

In the 1990s, a community of eight French Catholic monks lived in the mountains of Algeria in a time of civil war and terrorist violence. Their monastery was at the edge of a poor Muslim village, where they lived in harmony with their neighbors, providing the only accessible health care. As the surrounding political violence escalated, the monks were warned by the government to leave the country. But they felt called to remain among the people they served, despite the high probability of martyrdom. Despite their own fears.

Their abbot, Dom Christian, wrote a letter to his family in Advent, 1993, two years before he and his brother monks were beheaded by terrorists. Anticipating his own martyrdom, he insists to his loved ones that he is not exceptional, since so many others in that land were also at risk.

“My life,” he wrote, “is not worth more than any other — not less, not more. Nor am I an innocent child. I have lived long enough to know that I, too, am an accomplice of the evil that seems to prevail in the world around, even that which might lash out blindly at me. If the moment comes, I would hope to have the presence of mind, and the time, to ask for God’s pardon … and, at the same time, to pardon in all sincerity him who would attack me…”

What an extraordinary thing to say: Here is a good and humble and holy man confessing his own complicity in the evils of the world. And what does he hope for? He hopes for the presence of mind, in the very moment of being murdered, to ask forgiveness. Forgiveness not only for himself, but for his killer as well.

The end of his letter is addressed not to his family, his loved ones, but to the stranger who will one day kill him, the stranger whom he calls “my friend of the last moment.”

“And to you, too, my friend of the last moment, who will not know what you are doing. Yes, for you, too, I wish this thank-you, this “A-Dieu,” whose image is in you also, that we may meet in heaven, like happy thieves, if it pleases God, our common Father.” [x]

Dear reader, imagine that!

[i] Rowan Williams, Looking East in Winter: Contemporary Thought and the Eastern Christian Tradition (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021), 194. Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, goes on to say that “we can perhaps begin to understand why Evagrios can say that apatheia, our liberation from defensive and aggressive instinct, is the gateway to love—as well as to a justice that has some claim to be a little more transparent to the just vision that God has for the creation.”

[ii] From “Compline,” the penultimate poem of Auden’s Horae Canonicae (the Canonical Hours, which take us through successive portions of one particular day: Good Friday).

[iii] Susan Sontag, The New Yorker, September 24, 2001.

[iv] Bariq’s organization is Al-Shabaka, the Palestinian Policy Network. He was interviewed for The New Yorker by Isaac Chotiner: “Where the Palestinian Political Project Goes from Here” (Oct. 11, 2023):

https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/where-the-palestinian-political-project-goes-from-here

[v] Ruth Ben-Ghiat, “What Will Be the Destiny of Netanyahu?” (Oct. 12, 2023):

https://lucid.substack.com/p/what-will-be-the-destiny-of-netanyahu

[vi] Suzy Hansen, “Twenty Years of Outsourced War,” New York Review of Books (October 19, 2023), 26-28.

[vii] Auden’s “Epitaph on a Tyrant” is rendered in a plaintively sung version by Tom Rapp under the title “Footnote” (Pearls Before Swine, These Things Too). That’s where I first discovered it 50 years ago, and that last line still haunts me.

[viii] Nicholas Kristof, “What Does Destroying Gaza Solve?”, New York Times (Oct. 15, 2023)

[ix] Simone Weil, quoted in Robert Zaretsky, The Subversive Simone Weil: A Life in Five Ideas (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021), 155. For more on Weil and war: https://jimfriedrich.com/2022/03/01/we-must-love-one-another-or-die-what-does-the-iliad-tell-us-about-the-invasion-of-ukraine/

[x] The full story and its texts may be found in Bernard Olivera, How Far to Follow? The Martyrs of Atlas (Petersham, MA: St. Bede’s Publications, 1997). The story is also beautifully and movingly told in the film, Of Gods and Men (2010), directed by Xavier Beauvois.