Only a tramp was Lazarus’ sad fate

He who lay down by the rich man’s gate

To beg for some crumbs from the rich man to eat

But he left him to die like a tramp on the street

— Grady and Hazel Cole, 1939

Jesus was a great storyteller. He knew how to use a good story not just to make a point, but to change lives. But today’s story isn’t quite like any other parable. It’s the only one where a character is given a name. The poor man is called Lazarus, a variant of Eleazar, which means “God helps.” The rich man is unidentified in Scripture, but tradition has given him the name Dives. That’s Latin for “rich guy,” so readers of the Latin Bible began to treat it as his proper name.

This is also the only gospel parable about the afterlife.[i] Most scholars suspect it to be a version of a popular Egyptian folk tale widely told the in the first century. The fact that it makes it into Luke’s gospel suggests that Jesus liked the story well enough to use it in his own preaching.

It’s easy to see why people loved the story in a time when economic inequality was as appalling as it is in America today, where the 3 richest billionaires have more money between them than the bottom 50%. In first-century Palestine, the rich had scooped up most of the land and money, leaving tenant farmers with pretty much nothing of their own, while those who hired out as laborers got only starvation wages. So the idea of a great reversal of fortune was an appealing and consoling image.

The reversal theme certainly resonated with St. Luke, whose gospel, more than any other, expresses a “preferential option for the poor.” [ii] We hear this in Mary’s Magnificat: “He has cast down the mighty from their thrones, and has lifted up the lowly. He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty.” And we hear it in the Beatitudes: “Blessed are you poor, for yours is the kingdom of heaven.”

A twelfth-century Italian bishop, Bruno di Segni, said of this parable, “These words are most necessary both for the rich and for the poor, because they bring fear to the former and consolation to the latter.” [iii] In Herman Melville’s 19th-century novel Redburn, his protagonist invokes the parable when he cries, “Tell me, oh Bible, that story of Lazarus again, that I may find comfort in my heart for the poor and forlorn.” [iv]

We all love reversal stories, where the bad get their comeuppance and the lowly are given a happy ending. I have to confess that I myself would take pleasure in a story where, say, the governor of Florida is tricked into boarding an airplane, only to find himself dropped in the middle of a burning desert, with nothing but the desperate hope that a passing migrant might appear with a canteen of water. “Oh Señor, have mercy on me! I beg you, give me a drop of your water to cool my tongue!”

So is Jesus telling a reversal story in the parable of Dives and Lazarus? Or is he doing something else? The Bible certainly can be critical of wealth’s dark side. We’ve heard plenty of that in today’s readings:

Woe to those who are at ease in Zion,

and for those who are complacent on the mount of Samaria…

Woe to those who lie on beds of ivory,

and sprawl on their couches,

stuffing themselves with lamb and veal,

singing idle songs and drinking wine by the bowlful,

who anoint themselves with the finest oils,

but are not grieved over the ruin of Joseph. (Amos 6: 1, 4-6)

And St. Paul, in his first letter to Timothy, warns that “those who want to be rich fall into temptation and are trapped by many senseless and harmful desires that plunge people into ruin and destruction. For the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil, and in their eagerness to be rich some have wandered away from faith and pierced themselves with many pains.” (I Timothy 6:9-10)

But while the parable presents a strong contrast between situations of extreme wealth and extreme poverty, between high social status and low social status, between easy pleasure and terrible suffering, the point is not about changing places, or even about trying to reduce the contrast to some extent—a little less for the rich, a little more for the poor. This parable isn’t about making the game fairer, but about changing the game entirely.

Right now, in our time, our country, the game is so much about individual winning. The lucky ones win the lottery, invent the Internet, crush the competition, or throw more touchdowns than interceptions. The rest must fend for themselves. Dog eat dog. There have been notable attempts to counter the personal, social, and environmental damage of our careless individualism, but in the absence of a more widely supported vision of the common good, it continues to be an uphill battle. Can we order our lives and our society to be more in accord with divine intention? We’d better. As W. H. Auden put it on the eve of World War II, “We must love one another or die.” [v]

We all enjoy the hymn, “All things bright and beautiful,” celebrating the wonderful world God has made: “Each little flower that opens, each little bird that sings,” and so on. But one verse—thankfully scrubbed from our hymnal—celebrates an archaic social order as divinely ordained:

The rich man in his castle,

The poor man at his gate,

He made them, high or lowly,

And ordered their estate.

In the kingdom of God, the economy of God, such sundering of neighbor from neighbor is definitely not bright and beautiful. We all belong to one another; we are all intended to share God’s gifts in just measure. To forget this is to choose death and hell.

Kathleen Hill, an American writer, lived in Nigeria when the traditional cooperative social ethic was being eroded by the lingering effects of colonial rule. She tells of a driver who sped by a hit-and-run victim lying on the side of the road. He didn’t stop because he was afraid that if he put the wounded man into his car, he’d get bloodstains on his new seat covers. “He’d felt no need to apologize,” Hill said, “no need to feel ashamed. It was a culture of money that was growing in Nigeria, a new emphasis on personal wealth.… [N]ow, without the play of traditional values that had connected one person to another, there seemed no limits to self-interest, to the tendency to regard someone else exclusively in the light of one’s own personal imperatives.” [vi]

Where there are no limits to self-interest, no one is my neighbor. Dives feasts inside his mansion, while Lazarus starves on the street. And never the twain shall meet. I think that Jesus would say that Dives was in hell from the start. He didn’t have to die to get there.

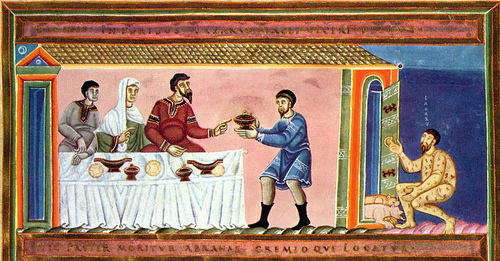

But is this state of separation and disconnection the way things must always remain, now and forever, Amen? Is there any chance for the twain to meet? I think the key to this parable is the gate. The rich man is on one side; Lazarus is on the other. In the story, the gate never opens. In fact, its role as a barrier eventually translates into an uncrossable chasm in eternity.

like Dives’ view of Abraham and Lazarus across the great chasm.

In the parable, Dives in hell is able to see, across that chasm, Lazarus at ease in the bosom of Abraham. But the gap between them is uncrossable. If only he had opened his gate and experienced Lazarus as a fellow child of God—not just a tramp on the street—there would be no uncrossable chasm between them now. He wouldn’t be stuck in the lonely hell of self-interest and self-isolation. It turns out that the closed gate keeping Lazarus out has also been keeping the rich man in. Even after death he remains in the prison he built for himself, behind the locked gate preventing the communion for which every person is made.

New Testament scholar Bernard Brandon Scott says this about the gate: “In this parable the rich man fails by not making contact.… The gate is not just an entrance to the house but the passageway to the other.… In any given interpersonal or social relationship there is a gate that discloses the ultimate depths of human existence. Those who miss that gate may, like the rich man, find themselves crying in vain for a drop of cooling water.” [vii]

“I came that you might have life,” Jesus said, “and that you may have it more abundantly” (John 10:10). So is there abundant life in the rich man’s future? Can the chasm ever be bridged by repentance and mercy? Ebenezer Scrooge, after being shown what a mess he was making of his own future, put this question to the final spirit in A Christmas Carol,:

“Are these the shadows of the things that Will be, or are they shadows of things that May be, only? Men’s courses will foreshadow certain ends, to which, if persevered in, they must lead. But if the courses be departed from, the ends will change. Say it is thus with what you show me.” [viii]

Can there be a different outcome to the story of Dives and Lazarus? A couple of poets have explored interesting options. James Kier Baxter (1926-1972) of New Zealand concentrates on Dives, who is far worse off than Lazarus even before he departs this life:

Two men lived on the same street

But they were poles apart

For Lazarus had crippled bones

But Dives a crippled heart

In an intriguing twist, Baxter leaves Lazarus on earth and puts Dives in the Divine Presence. ‘My poor blind crippled son, [God] said, / ‘Sit here beneath My Throne.” And instead of eternity in Hades, Dives is given a chance to change his life:

‘Go back and learn from Lazarus

To walk on My highway

Until your crippled soul shall stand

And bear the light of day,

And you and Lazarus are one

In holy poverty.’ [ix]

Canadian William Wilfred Campbell (1860-1918) focused his poem on Lazarus, giving him a voice he never had in the original parable. While enjoying the bliss of the afterlife, Lazarus is suddenly troubled by a “piercing cry of one in agony, / That reaches me here in heaven.” It’s the rich man’s anguished plea from hell, drowning out the more amiable sounds of heaven.

So calleth it ever upward unto me

It creepeth in through heaven’s golden doors;

It echoes all along the sapphire floors;

Like smoke of sacrifice, it soars and soars;

It fills the vastness of eternity.…

No more I hear the beat of heavenly wings,

The seraph chanting in my rest-tuned ear;

I only know a cry, a prayer, a tear,

That rises from the depths up to me here;

A soul that to me suppliant leans and clings.

O, Father Abram, thou must bid me go

Into the spaces of the deep abyss;

Where far from us and our God-given bliss,

Do dwell those souls that have done Christ amiss;

For through my rest I hear that upward woe.

Lazarus can’t ignore the sinner’s plea, nor does he want to. In a replication of both the Incarnation and the Harrowing of Hell, he begs “Father Abram” to let him descend to the uttermost depths on a mission of redemptive love. The journey is immense, and when the poem ends Lazarus is still on the downward way, with cries of pain ahead, shouts of glory behind. As he traverses the infinite gap between heaven and hell, we suspect this outward motion of self-diffusive love will go on and on, until that day when the tears are wiped from every eye and “God is all in all” (I Corinthians 15:28).

Hellward he moved like radiant star shot out

From heaven’s blue with rain of gold at even…

Hellward he sank, followed by radiant rout…

‘Tis ages now long-gone since he went out,

Christ-urged, love-driven, across the jasper walls,

But hellward still he ever floats and falls,

And ever nearer come those anguished calls;

And far behind he hears a glorious shout. [x]

It’s a striking image: Love perpetually reaching for the hopeless and the lost, opening every gate, overcoming every obstacle that separates us from God. However, in the original parable, the rich man’s repentance is not off to a promising start. In his cry from hell, Dives doesn’t deign to speak to Lazarus at all. Instead, he asks Abraham, a personage he considers of equal status, to treat Lazarus like a common servant. “Have him dip a finger into cool water and come to me, so he can drip it onto my tongue.” Even in his agony, the rich man’s arrogant self-interest is unabated.

In Luke’s gospel, this parable always ends the same way, no matter how many times we read it. Dives will stay stuck in the prison of his own making for as long as the story is told. If we want a new ending, we must write it with our own lives and times, as we push through the gate into a deeper union, a more loving communion with our fellow creatures. This is not only radically personal work, it is also the collective endeavor of Church and society. In a time when the common good and neighborly love are in acute peril, love and mercy ceaselessly call us to choose the better way.

This homily was written for the Sixteenth Sunday after Pentecost at St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, Bainbridge Island, Washington.

[i] Matthew 25: 31-46 (The sheep and the goats) is also about the afterlife, but many scholars say it does not fit the definition of a parable.

[ii] The term was popularized by Liberation theologians and activists in Latin America in the 1960s as a key element of Catholic social teaching.

[iii] Cited in Stephen L. Wailes, Medieval Allegories of Jesus’ Parables (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1987), 255.

[iv] Herman Melville, Redburn (1849), ch. 37.

[v] W. H. Auden, “September 1, 1939.”

[vi] Kathleen Hill, She Read to Us in the Late Afternoons (Encino, CA: Delphinium Books, 2017), 57.

[vii] Bernard Brandon Scott, Hear Then the Parable: A Commentary on the Parables of Jesus (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1989), 159.

[viii] Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843), Stave IV.

[ix] James Kier Baxter, “Ballad of Dives and Lazarus,” in Divine Inspiration: The Life of Jesus in World Poetry, eds. Robert Atwan, George Dardess, & Peggy Rosenthal (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 260-261.

[x] William Wilfred Campbell, “Lazarus.” For complete text: https://www.poetryexplorer.net/poem.php?id=10045686