(Gettysburg, July 1863: the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War).

“War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it; and those who brought war into our Country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out.”

— William Tecumseh Sherman, 1864

“I confess, without shame, that I am sick and tired of fighting—its glory is all moonshine; even success the most brilliant is over dead and mangled bodies, with the anguish and lamentations of distant families, appealing to me … for sons, husbands, and fathers … it is only those who never heard a shot, never heard the shriek and groans of wounded and lacerated … that cry aloud for more blood, more vengeance, more desolation.”

— William Tecumseh Sherman, 1865

When General Sherman’s troops pillaged and burned their way across Georgia in the American Civil War, they ignored the conventions of traditional warfare. It wasn’t enough to defeat their counterparts in battle. The enemy’s support system had to be destroyed as well. Infrastructure, manufacturing, and food supply were all fair game. Regrettably, many civilians would have to pay the price of such “total war,” but breaking the popular will through suffering was seen as a critical means for hastening surrender. According to this heartless logic, the crueler the war, the sooner the peace.

Sherman wrote “war is cruelty” in a letter to the Mayor and Councilmen of Atlanta, insisting that the city be evacuated in advance of its wholesale destruction by federal troops. “You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war,” he told them. “They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home, is to stop the war, which can only be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.” [i]

Sherman’s cruelties helped end the Civil War. But a few months after the Confederate surrender, he seemed to be haunted by the memory of all those “dead and mangled bodies” strewn across the American landscape. Though the guns of war had been silenced, “the shriek and groans” of the fallen still echoed in his head.

The current war in Gaza is rooted in its own particular history of grievance, wounding, hate, and revenge, and it’s happening in a time and a culture very different from Sherman’s America. Nevertheless, when novelist Stephen Crane described Civil War battles as an impersonal force, a mechanism operating independently of human will, he could have been describing Gaza. War is like “the grinding of an immense and terrible machine,” he wrote in 1895. “Its complexities and powers, its grim processes” have one end: to “produce corpses.”

The Gaza war, in its first 40 days, has produced over 13,000 corpses, most of which were civilian non-combatants, including thousands of women and children. The ratio of Palestinian deaths to Israeli deaths is 10 to 1. Ten eyes for an eye. How many deaths will it take till we know that too many people have died? [ii]

For the extremists on both sides, military victory is not enough. Their opponents need to be “disappeared” from history. Instead of seeking peace by implementing just relations between the contending parties, they would rather remove the “other” from the equation altogether. End of story.

The terrible finality of such a goal calls to mind a scene in The Stranger, a 1946 film noir directed by Orson Welles, who plays Franz Kindler, a Nazi war criminal fleeing his past by posing as Professor Charles Rankin at a New England college after the war. During a dinner party with his new bride Mary (Loretta Young), Wilson (Edward G. Robinson, playing a government agent with suspicions about Rankin’s true identity), and several academic colleagues discuss Germany’s postwar future,

“Charles” argues that “the German” is incapable of peace. “He still follows his warrior gods, marching to Wagnerian strains, his eye still fixed on the fiery sword of Siegfried … The world is waiting for the Messiah, but for the German, the Messiah is not the Prince of Peace.” His words are a pretense—he himself is German—but as the conversation continues, his mask slips just enough to give a brief glimpse of his genocidal worldview.

“But my dear Charles,” says one of his colleagues, “if we concede your argument, there is no solution.

Kindler/Rankin: Well, sir, once again I differ.

Wilson: Well, what is it, then?

Kindler/Rankin: Annihilation—down to the last babe in arms.

Mary: Oh Charles, I can’t imagine you’re advocating a Carthaginian peace.

Kindler/Rankin: Well, as an historian, I must remind you that the world hasn’t had much trouble from Carthage in the past two thousand years. [iii]

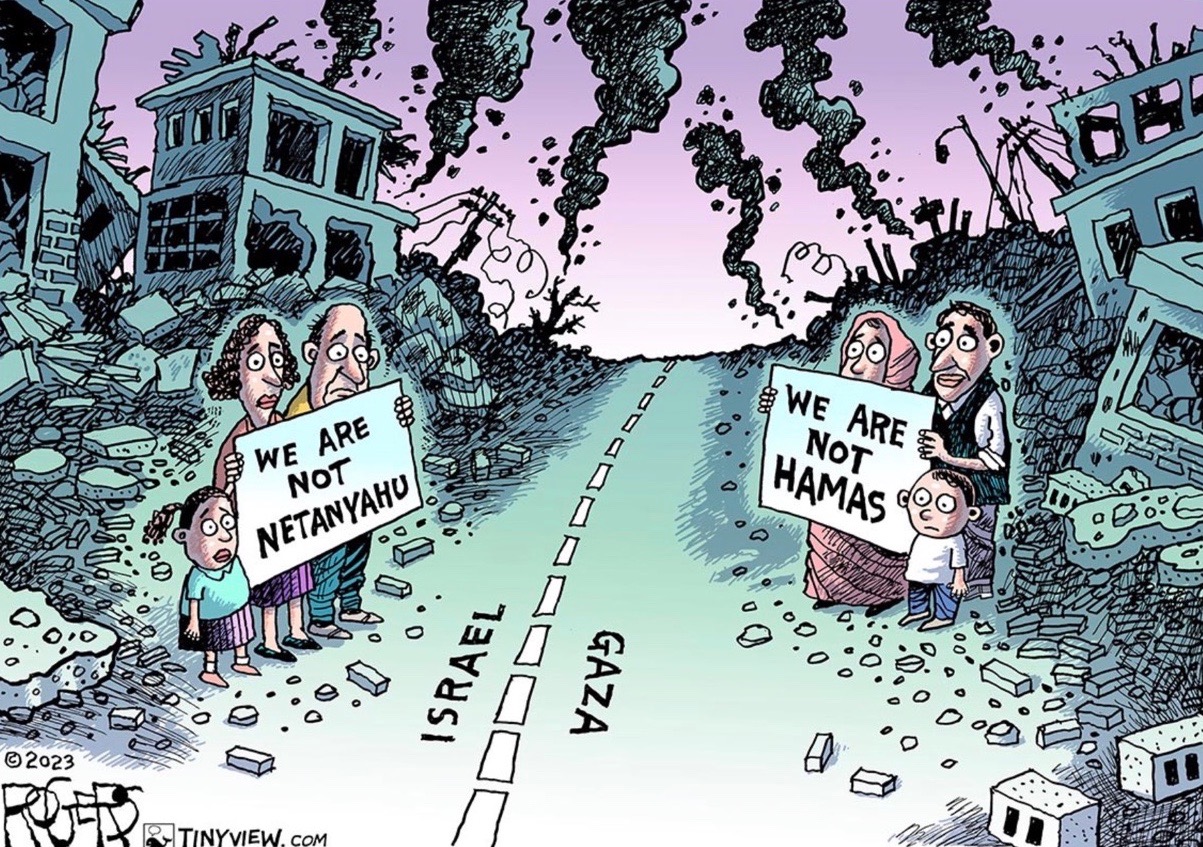

Annihilation of the other is not only supremely evil, it is strategically stupid. The more you kill, the more enemies you create. Violence, whether by terrorists or armies, will never bring lasting peace for Israelis and Palestinians. It can only perpetuate the futile Punch and Judy show of hit and hit back. Time for a new story. Can we get a rewrite?

The collapsing building calls to mind the bombing of Gaza.

In the fifth century B.C.E., the community of Israelites returned to Judah from a century of exile in Babylon. They set out to rebuild the ruined temple in Jerusalem and renew their identity as God’s people, dwelling in their promised homeland. The biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah record this challenging process. As Robert Alter notes in his celebrated translation of the Hebrew Scriptures,

“The community of returned exiles found itself in sharp conflict with other groups in the country, and the ideology promoted by both Ezra and Nehemiah was stringently separatist. Those who had remained in the land and claimed to be part of the people of Israel—in particular, the Samaritans—were regarded as inauthentic claimants to membership in the nation and were to have no role in the project of rebuilding.” [iv]

In a first-person account, Ezra reports his shock at finding that some Israelites, instead of keeping separate from the locals, had taken “foreign” wives for themselves and their children. “When I heard this thing,” he says, “I rent my garment and my cloak and I tore out hair from my head and my beard and I sat desolate” (Ezra 9:3) Why is he so upset? It’s because, as he put it, “the holy seed has mingled with the peoples of the lands.” As Alter explains,

“The traditional reason for avoiding intermarrying was to keep apart from pagan practices. Although Ezra has this rationale in mind, here he adds what amounts to a racist view: the people of Israel are a ‘holy seed’ and hence should avoid contamination by alien genetic stock.” [v]

The desire to preserve identity in the face of diversity has been around as long as humans have lived in communities, but separatist ideologies that devalue or demonize the “other” have terrible consequences. Sooner or later, they “produce corpses.”

It’s not just a problem for the Middle East. Just last week, in a chilling echo of Mein Kampf, the leading American fascist said that immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country.” And, he added, they—along with anyone who dares oppose him—are “vermin.” Such dehumanization, as history has repeatedly shown, opens the door to the Carthaginian solution: annihilation.

Not everyone in ancient Israel bought into the separatism of Ezra and Nehemiah. Another biblical book, written in the same post-exilic period, proposes an alternative way of being. It is the story of Ruth, a Moabite “foreigner.” Moab was a perennial enemy of Israel. Any interaction with Moabites was forbidden in the Torah. Despite this, an Israelite who happens to live in Moab takes Ruth as his wife. When he dies, her mother-in-law Naomi decides to return to her hometown of Bethlehem. Although she expects Ruth to remain with her own people, Ruth has other ideas. She is unwilling to break the bonds of devotion between herself and Naomi:

Wherever you go, I will go with you. And wherever you lodge, I will lodge.

Your people is my people, and your god is my god (Ruth 1:16).

Once in Bethlehem, she meets Boaz, her future husband. Like her first spouse, he’s an Israelite. In this story, intermarriage is not a problem. Not only is Ruth given one of the few happy endings in the Bible, that Moabite woman becomes the honored ancestor of King David. Cultural difference turns out to be a gift! This charming story challenges the dominant separatist ideology by picturing a much better world. As Alter explains,

“Unlike the narratives from Genesis to Kings, where even pastoral settings are riven with tensions and often punctuated by violence, the world of Ruth is a placid, bucolic world, where landowners and workers greet each other decorously with blessings in the name of the Lord … In the earlier biblical narratives, character is repeatedly seen to be fraught with inner conflict and moral ambiguity. Even such presumably exemplary figures in the national history such as Jacob, Joseph, David and Solomon exhibit serious weaknesses, sometimes behaving in the most morally questionable ways. In Ruth, by contrast, there are no bad people.” [vi]

Is the Book of Ruth only a fairy tale? Or is the promise of a diverse humanity living in peace a dream worth inhabiting? In a region where political success is so rare that people can’t even imagine progress; where mutual trust is on life support and intransigence rules; where existing leadership is part of the problem; where everyone is too busy killing, dying or grieving to think clearly about a viable future, such a dream may seem absurd. Nevertheless, considering the present alternative, perhaps a dream is required to supply the faith to advance, step by step, toward the world God intends for us.

It will be a long and arduous journey—risky, too, but not as risky as remaining stuck in Deathville. It’s best to start soon—and to travel light. Let go of things that won’t be needed in the better story that lies ahead: mistrust, fear, and vengeance; discouragement, despair, and hopelessness; terror, settlements, and apartheid; despots, crooks, and liars. Along the way, plant seeds of peace, justice, patience, gentleness, kindness, humility, generosity, forgiveness, love and mercy wherever you can.

It’s been said that sin is the “refusal to be touched by the pain of others.” [vii] And the antidote, says Cynthia Bourgeault, is kenosis: the self-emptying whose name is Love:

“When surrounded by fear, contradiction, betrayal; when the ‘fight or flight’ alarm bells are going off in your head and everything inside you wants to brace and defend itself, the infallible way to extricate yourself and reclaim your home in that sheltering kingdom is simply to release whatever you are holding onto—including, if it comes to this, life itself.” [viii]

[i] Letter from W.T. Sherman to James M. Calhoun, E.E. Rawson, and S.C. Wells, September 12, 1864.

[ii] The line is borrowed from Bob Dylan. In Israel and Gaza, the answer is still blowin’ in the wind.

[iii] The screenplay for RKO’s The Stranger was written by Anthony Veiller, with uncredited contributions from John Huston and Orson Welles. The term “Carthaginian Peace” comes from Rome’s brutal subjugation of Carthage after years of warfare. In 146 B.C.E., the Romans burned Carthage to the ground and slaughtered most of its inhabitants.

[iv] Robert Alter, The Hebrew Bible, Vol. 3: The Writings (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019), 804.

[v] Ibid., 825 n. 2.

[vi] Alter, 622.

[vii] Rowan Williams, Looking East in Winter: Contemporary Thought and the Eastern Christian Tradition (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021), 221.

[viii] Cynthia Bourgeault, Centering Prayer and Inner Awakening (Cambridge, MA: Cowley Publications, 2004), 87.

The Stephen Crane quote is from The Red Badge of Courage.