What we have heard,

what we have seen with our eyes,

what we have looked at and touched with our hands—

the Word of life— this is our theme . . .

We declare to you what we have seen and heard,

so that you too may share our life. (I John 1:1,3)

The Easter Vigil is a night of wonders. Beginning after dark on Holy Saturday, God’s friends gather around a fire under the stars, as poets and singers, accompanied by the sounds of loon, whale and wolf, take us back to the beginning of time, when all things came to be. Then we follow the Paschal Candle, symbol of the risen Christ, into the Story Space to experience creative retellings of our sacred narratives, recalling God’s unfailing covenant with us throughout history. Theater, storytelling, music and multimedia immerse us in the rich play of Scriptural meanings. After that we process into the church, to the font of new birth, renewing our baptismal vows by candlelight. Suddenly, the contemplative quiet is broken by a great tumult of drums, bells, chimes (and sometimes fireworks!) as we welcome the first eucharist of Easter, sharing the feast of heaven with bread and champagne,and dancing our praises around God’s table.[i]

The Easter Vigil is the Christian dreamtime, the molten core of our worship life, but for those who missed it, who didn’t arrive at church until Easter morning, it exists only as a rumor of something quite out of the ordinary, hard to imagine after the fact. I could describe what happened in great detail, but a considerable amount of the joy and the wonder would be lost in the telling. Hearing about it is not the same as actually experiencing it.

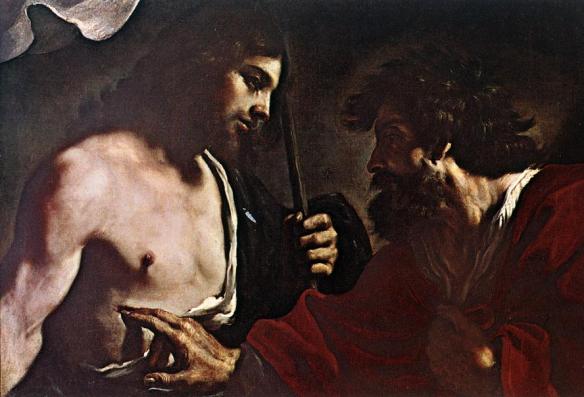

Just ask Thomas the Doubter. He had missed out when the risen Christ first appeared to the other disciples.[ii] Oh Thomas, it was so amazing, so incredible! If only you had been there. “No way,” he says. “I just can’t see it. You must have been dreaming.” And so Thomas became known as the Doubter, and the Church made him patron saint of the blind. And yet, we always honor Thomas by telling this story on the Second Sunday of Easter, as if to say,

We welcome those who take questions seriously;

we believe that faith and doubt must dance together;

we are in fact a community of those

who wrestle with God’s absences

as well as God’s presences.

Another Thomas, the 20th century Welsh poet and Anglican priest, R. S. Thomas, wrote a poem about this gospel story:

… His are the echoes

We follow, the footprints he has just

Left. We put our hands in

His side hoping to find

It warm.[iii]

The sense of belatedness, of arriving too late, haunts every religious tradition whose foundations lie in definitive past events. Even Jesus’ closest friends, who had shared a last supper with him just days before, felt the warmth of his presence quickly cooling into memory.

But then they discovered that Christ does not come to us out of the past, locked within well-worn expectations. The risen One comes out of the future, often in a form we don’t expect: the stranger, the other, the outcast, even the enemy. If we only look for Jesus in the vacated tombs of past experience, we will get the admonishing angel: “He is not here. He’s already waiting for you somewhere else. Go and see.”

For a while after the resurrection of Jesus, there were sensory appearances in a form the disciples could recognize and relate to in the old familiar ways. They spoke with him. They ate with him. They experienced his peace. And their primal witness remains vital. A positive identification of the risen One as the same person who died on the cross was essential to the core Easter message: Jesus lives! Not a memory, substitute, or simulacrum, but a continuing presence which not even death could kill.

These appearances eventually ceased, but before they did, Thomas finally got his moment with the Jesus he had known. It blew away his doubts and drove him to his knees. But then Jesus said, “Blessed are those who have not seen, and yet believe.” And later he said, “I am with you always, even to the end of time.”

In other words, Christ’s resurrection is not limited to the personal experiences of a few first century people. If that were the case, then it would be something we could only hear about later but never experience for ourselves. Like Thomas before his late encounter, we would have only Christ’s absence.

But the Easter faith affirms the continuing presence of the living Christ among us, now and always. That presence is not always clear or obvious. Even the saints wrestle with doubt and absence. Sometimes divinity seems to withdraw for a time. Sometimes it is we who are absent— distracted, inattentive, looking in the wrong place, using the wrong language. Divine presence can’t be switched on, or grasped possessively. It is elusive. It is fond of surprise.

But we are not left without clues. Jesus tells us, “If you want to keep experiencing me, love one another. Forgive one another.”[iv] Thus we meet the risen Christ in the life of forgiveness, reconciliation, peace, justice, love. Where love and charity abound, there God is, there Christ is. It’s not enough to proclaim resurrection. We need to embody it.

As Rowan Williams explains: “the believer’s life is a testimony to the risen-ness of Jesus: he or she demonstrates that Jesus is not dead by living a life in which Jesus is the never-failing source of affirmation, challenge, enrichment and enlargement.”[v]

The Book of Acts tells us the first believers made their common life a “laboratory of the resurrection”[vi]— not just a theological mystery but a daily practice, rejecting the economics of selfishness and scarcity for radical acts of generosity and compassion. Their belief was a practice of entrusting themselves to the renewing force of divine love that is never exhausted by the sufferings of the world. In other words, resurrections have consequences.

These are large claims, of course, and not universally embraced. But for me resurrection’s greatest challenge is not that I am being asked to believe something difficult; it is that I am being asked to do something difficult:

to be utterly transformed by immersion into the dying-and-rising of Christ,

to become my baptismal self,

to cast off the rags of ego and fear

and be clothed in “garments of indescribable light.”[vii]

It’s not intellectual or empirical doubt that makes me hesitate at the threshold of the risen life. It’s not that I think such transformation to be impossible. No, for countless saints have already demonstrated its possibility. My doubt concerns myself. Am I up to it?

Have you ever stood on a rock

twenty feet above the surface

of an icy mountain lake?

The summer day is hot;

you know the water will refresh you.

You are caked with grime and sweat from hours of hiking.

It will feel so good to wash it all away.

You imagine the explosive energy of the splash,

the exhilarating shock of glacial waters.

And you anticipate the joy of swimming,

the bliss of weightlessness

setting you free from the gravity of things.

But you hesitate.

You doubt.

The water is dark.

Are there rocks beneath the surface?

Will the sudden cold take your breath away?

The very act of stepping out into nothing

is resisted by an inner voice of self-preservation.

There’s no way to stop the mind’s questions or the body’s fears.

They persist for as long as you stand there.

The lake doesn’t get any warmer.

The boulder doesn’t get any lower.

Then you just lean out into space

and let yourself go.

Related Posts

Just a dream? Reflection on the Easter Vigil

[i] Although most Easter Vigils don’t happen quite this way, they can, and (IMHO) should. I have been curating them this way for several decades in various worship communities, and I believe that such a rich interplay of ritual and the arts, engaging all the senses in a multigenerational, visionary happening, at once contemplative, playful, and ecstatic, does true justice to our celebration of the Paschal Mystery – the passage from darkness and death into the risen life..

[ii] John 20:24-29

[iii] R.S. Thomas, “Via Negativa,” Collected Poems: 1945-1990 (London: Phoenix Giant, 1995), 220

[iv] My gloss on the Farewell Discourse in the Fourth Gospel (John 14-17)

[v] Rowan Williams, Resurrection (New York: The Pilgrim Press NY, 1984), 62-3

[vi] Dumitru Staniloae, q. in Olivier Clement, The Roots of Christian Mysticism (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press, 1993), 82

[vii] Pseudo-Macarius (desert father, c. 400, Mesopotamia/Asia Minor) First Homily