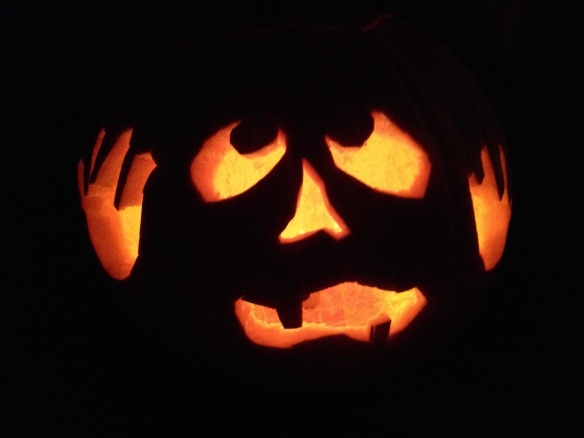

Morris dancers lead “Lord of the Dance” at the Puget Sound Christmas Revels (Photo: Puget Sound Revels)

“Everyone who ends up going to the Revels and loving it wants to say to the people who missed it, ‘You have got to see this!’ They don’t sit their friends down and try to explain this amazing thing. They just want them to experience it. And that’s why we all want to take people who haven’t been before. That’s why I started the Revels in Puget Sound. I wanted people to feel it, right to their core, because that’s where it ultimately touches us, and all the talking in the world about what is a Revels and what isn’t, or you’ll like this about it or this is how it’s woven together – it isn’t the same as experiencing it. What I do say to people is: it’s not a concert, it’s not a play, it’s a kaleidoscope of music and dance and drama that all create a sense of a celebrating community.”

– Mary Lynn, Puget Sound Revels

Imagine yourself in a village square or a great hall in a culture where the community gathers every December to contradict the dark and the cold with high-spirited celebrations of life, warmth, and hope for renewal. Tuneful voices are raised to “joy, health, love and peace.” Dancers circle and leap their defiance of winter’s immobilizing spell. Playful mummers depict the dying of the old and the rising of the new. As you watch and listen, you find your own deepest impulses awakened and expressed, and before you know it, you too are singing and dancing along with everyone else.

Such elemental festivity is nearly impossible in the United States, where ritual traditions have been so fragmented, thinned and trivialized, and communal public life verges on extinction. But the Christmas Revels returns us to that celebrating village, that magically inclusive hall where the songs are sung and the dances are danced and the shadow of death is turned into morning.

When the late John Langstaff staged the first Christmas Revels in New York City in 1957, he was trying to recapture and share the communal joy of the caroling parties given by his music-loving family during his childhood. As he later wrote:

“My love of the carols and traditional music I grew up with eventually broadened into a fascination with folk material of every sort – rituals, music, dancing and drama. All have become essential elements in Revels. Revels’ focus on active audience involvement grew out of those same roots, and especially out of my awareness that few things bond people as powerfully as singing together.”

In 1971, Langstaff began to make the Revels an annual event in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and over the years it has spread to nine other American communities on the West and East coasts as well as Texas and Colorado. Here in the Northwest, the Christmas Revels has been celebrated in both Puget Sound and Portland since 1994.

Each local Revels group chooses its particular theme for the year. It might be medieval, Celtic, American (Appalachian, African-American, Shaker), Scandinavian, Victorian, or the Italian Renaissance.. At the local Revels I’ll be attending this week at Tacoma’s Rialto Theater near Seattle, the subject will be the storied pilgrimage along the Camino de Santiago.

The Christmas Revels always imagines a world better than the one we know, where high and low, rich and poor, find the distinctions between them blurred or even subverted, as the commonness of a shared humanity blends strangers and adversaries into a harmonious whole. This vision of true community is implicit in the way that all classes, ages and types of people sing and dance together. But it is also revealed in the gentle mocking of anything that divides us. A king might learn wisdom from the lowly fool, or the rich might discover the poverty of their isolation from a world of sharing.

Such bridging of divides can be more than fictional. I remember a California Revels in 1990, at the end of the Cold War. Toward the close of the evening, an ensemble of Russian dancers joined hands with the American cast for a circle dance during the Shaker hymn, “I Will Bow and Be Simple.” I noted the rapt attention of the young children around me in the audience, and it struck me that the very first fact they were learning about Russians was that they were people who danced with us.

Traditional celebrations usually contain an element of chaos and “misrule,” unleashing the energies from which new possibilities are born. In sword dances, mummer’s plays, and traditional dances and games, the Revels are deeply playful. But even as you are entertained, you are reminded of your mortality––and your longing.

Solstice rituals have always included mock battles, where a symbolic figure dies and rises again, like the earth in its seasons or the sun in its celestial journey. No matter how comic, these contests speak powerfully to our own anxieties when the dark and the cold are upon us.

In one production, during the feasting and celebration of a medieval court, the king was confronted by an intruder. It was Death, in the form of a giant puppet made of dark translucent gauze. The antagonists crossed swords, and the king was defeated. Only the lowly royal Fool remained as the last line of defense between Life and Oblivion.

Following the King’s death, the Fool entered to find the royal throne occupied by a motionless skeleton. After some tentative stabs at interaction, the Fool took the skeleton in his arms and danced around the stage with it. The daring incongruity of this image was quite funny, but it was also breathtaking––life winning after all, not with weapons but with dancing. “I am the Dance and I still go on.”

Finally, the Fool danced into the wings with the skeleton, and when he returned, he carried the skull in his palm as a trophy, and Death’s disjointed bones were now harmless playthings held by the laughing children who followed after.

“Revels came out of human community in a way we all can feel,” says Mary Lynn, founder and producer of the Puget Sound Revels. “It came out of celebration, it came out of mourning, it came out of birth and death and hope, it came out of all the things that are part of our lives. No matter how different ‘the village’ is, we face all those things, in every time and place.”

Although the confrontation with darkness and death is a pivotal point in every Revels, allowing us ritually to release our anxieties about human fate in a time of darkness, the overall tone of a Revels is the very opposite of somber. Good cheer rules every performance. A fluid spectacle of characters, costumes and staging engages both mind and sense. The energy of dancers and mummers is irrepressible and often hilarious. And the music is the heart of Revels magic. Spanning a wide range of seasonal songs and instrumentals, it is always beautifully performed.

Sometimes there are stunning solo voices in a Revels performance, like Appalachian balladeer Jean Ritchie, or the Irish “sean-nos” singer Sean Williams. But the essence of Revels lies in the choruses of adults and children, whose harmonious diversity of voices images the very nature of community.

The audience is always invited to enter that community––not just as witnesses, but as participants. Singing is the principal bridge between spectators and cast. Everyone joins in on familiar carols and “Dona Nobis Pacem,” and the Revels finale is a stirring mass rendition of the “Sussex Mummers’ Carol,” whose lyrics pour seasonal blessing on everything in sight.

The miracle of Revels is that for a couple of hours an audience of strangers believe themselves to be part of something larger than their atomized private realities. They are ushered into a world of wonders, nourished by the food of human community, and sent back into the streets with smiling faces.

As Mary Lynn observes, Revels does something special to those who come: “Revels is about community, and feeling a part of that village on stage.” She is quick to point out that it’s not the village we live in now, nor is it a village from an idealized past. It’s a ritualized image of a human future, with the power to attract us toward a truer embodiment of community. “It’s the village that should be,” she says. “And at some point, you find yourself invited into that village, onto the stage.”

This point comes at the end of the first half of every Revels. A singer intones Sydney Carter’s song, “Lord of the Dance,” as white-clad Morris dancers, with their bells and red handkerchiefs, leap and dance around him. Meanwhile, other cast members move among the audience, inviting them to leave their seats for a line dance that goes up and down the aisles and spirals around the stage, as all repeat the chorus,

Dance, then, wherever you may be,

I am the Lord of the Dance, said he,

And I’ll lead you all, wherever you may be,

And I’ll lead you all in the dance, said he.

It’s a moment that many of us live for each year. For a few minutes, cast and audience are utterly one, dancing, dancing, wherever we may be. My sister Marilyn, who introduced me to the Revels many years ago, always races downstairs from her balcony seat at the California Revels in order to join the dancers moving toward the stage. There are so many people on their feet for the dance, you never know if you’ll reach the stage before the music ends. Marilyn always calls me later to report on the success of her quest. “I wondered whether I would make it to the stage this year, now that I’m 80,” she told me yesterday. “But I did it!”

Susan Cooper wrote a poem called “The Shortest Day,” recited at every Revels. She imagines all the generations who preceded us, burning their “beseeching fires all night long to keep the year alive.” She hears their joyful voices echoing down from their time into ours:

All the long echoes sing the same delight,

This Shortest Day,

As promise wakens in the sleeping land:

They carol, feast, give thanks,

And dearly love their friends,

And hope for peace.

And now so do we, here, now,

This year and every year.

Welcome Yule!

Because the Revels are so unique, they are hard to describe. Most of the already initiated don’t even try. They merely tell their friends to trust them and come along. “You just have to experience it!” is the common cry. It’s like trying to tell someone what it’s like to be in love.

Debbie Birkey, a publicist for the Puget Sound event, moved and performed in local folk music circles for years without ever hearing of Revels. In the late nineties her husband took her to her first performance, and it was a revelation. “It’s incredible that I was here in Tacoma and this fabulous thing was going on and I didn’t know about it,” she says. “Then we came to the Revels and after about five minutes of being swept away, I turned to my husband and said, ‘These are my people!’ And it’s just swept me up ever since. So I’ve been in about eight or nine shows, and then I started helping with publicity. Here is this amazing thing going on in Tacoma and people don’t know about it, and I can’t imagine why that is. So I feel that it’s my mission to change that.”

Revels seems to inspire this kind of fervor. A typical audience will include some who were drawn by the publicity, but the majority are either loyal regulars who come year after year, or first-timers who have been dragged there by friends, because Revels is something you want to give to everyone you love.

Sharing Revels can be an obsession, and I myself confess to it. 2017 will mark my twenty-ninth Revels (10 in Oakland, 19 in Tacoma). I never go without bringing others along. And this year, as always, we will join hearts and hands and voices with all the other revelers, no longer strangers in “the village that should be.”

The Puget Sound Revels, focusing on the Camino de Santiago, has two remaining performances at the Rialto Theater in Tacoma, WA: December 19 & 20 at 7:30 p.m. While some of the nationwide Revels have completed their run, you can still get to performances in Portland (OR), Santa Barbara (CA) and Boulder (CO). For a list of all ten Revels sites: https://www.revels.org/revels-nationwide/

A version of this piece originally appeared in Victory Review, a Northwest folk music journal, in 2005.