And when all the stars and sentimental songs dissolved to day,

There was nothing left to sing about but hard love.

— Bob Franke, “Hard Love”

Yet even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.

— Burial Office, Episcopal Book of Common Prayer

“Bob Franke! Ten years ago, one of his songs literally saved my life.” That’s what a theology professor told me back in the nineties, when I was catching a ride with her to Salem from the Massachusetts coast. She taught at Harvard Divinity School and had offered to drop me at a friend’s house on her way to work. “What’s your friend’s name?” she asked. I told her, and I have never forgotten her heartfelt response. But I was not surprised by it. Bob’s songs have been a source of comfort and healing for many of us over the years.

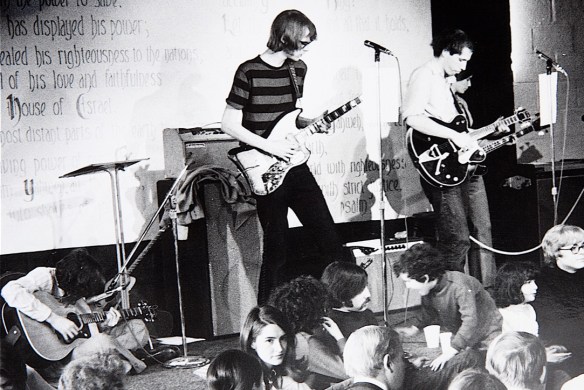

I first met Bob in 1969, when he was a student and aspiring singer-songwriter at the University of Michigan, and I was a Cambridge seminarian visiting Ann Arbor during spring break. Bob was part of an impromptu band I helped put together for the Easter liturgy at Canterbury House, the Episcopal campus ministry coffeehouse renowned not only for its folk concerts (Neil Young, Joni Mitchell and Richie Havens were on the bill that year), but also for its wonderfully creative alternative worship. On Easter morning, about 150 students and faculty descended into the gloomy basement “tomb,” until a clown in white face appeared to announce that “Christ is risen!” As the congregation exited the tomb into the light-filled hall above, our band played the opening hymn—“Mr. Tambourine Man.” Nothing like resurrection to make a “jingle-jangle morning.”

Easter Sunday, 1969

Canterbury House was also the first place Bob sang his own songs on stage. In the previous year, the headline act—the unpredictable Ramblin’ Jack Elliott—had wandered away between sets to get ice cream in Detroit, 45 miles away. During his long absence, someone asked Bob to fill in until Jack returned. And a star was born.

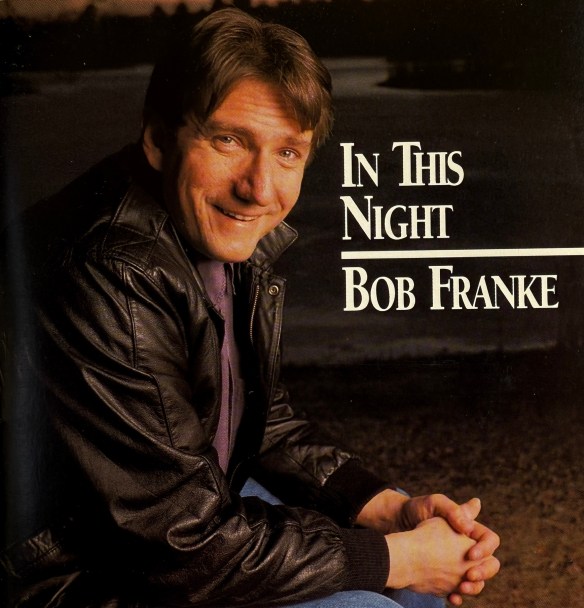

Bob was a faithful friend of God, an Episcopalian by tradition. He attended my seminary in Massachusetts for a year, but it soon became clear that, in his words, “a guitar fit better around my neck than a clerical collar.” But his songs, and the way he would speak about them in concert, became a unique ministry of illumination, comfort and blessing which touched so many lives. Bob himself put it this way:

“Whenever I sing, I’m trying to create in my listeners an awareness of the beauty and sacredness of their own lives, both individually and together, as a community. A woman came up to me recently and said that my story and my song put her relationship with her dad in a new light, gave her insight into her dad’s love for her. That’s all I need to take home from a show.”

Some of his work engages biblical topics, such as his Nativity carol, “Straw Against the Chill,” or “We’re Walking in the Wilderness.” Some lyrics incorporate Scriptural references (“new streams in the desert, new hope for the poor”). But most of his songs, whatever the topic, touch on fundamentally religious questions: yearning, journey, justice, death, loss, mercy, gratitude, love.

But it was always more than the songs with Bob, whose own authenticity, depth, humility and warmth made every concert an event of the heart. As music programmer Alan Korolenko describes the Bob Franke experience:

“No matter the size of the audience, you’re going to get an intimate evening with Bob. He just pulls everybody in, which is the key. You’ll meet other artists, and they’re not the same as their work. That’s not the case with Bob. He appeals to folk fans and general audiences, because he knows how to create a full, emotional journey, and how to share that journey. By the end, you’ve laughed and thought and cared; you’ve gotten to know the guy. He’s a class act.”

In the folk world, Bob’s songwriting has long been held in high esteem. Peter, Paul and Mary, David Wilcox, John McCutcheon, Sally Rogers, Martin Simpson, Lui Collins, Garnet Rogers, June Tabor and countless others have all recorded from his songbook. Claudia Schmidt has a beautiful version of “Hard Love,” one of the most truthful and hard-earned songs ever written on the subject.

Yes, it’s hard love, but it’s love all the same

Not the stuff of fantasy, but more than just a game

And the only kind of miracle that’s worthy of the name

For the love that heals our lives is mostly hard love

Bob’s melodies have a way of drawing you into a place of receptivity, where his words, so precise, truthful and unafraid, whisper their truth to your heart.

For the Lord’s cross might redeem us, but our own just wastes our time. (“Hard Love”)

There’s a hole in the middle of the prettiest life,

so the lawyers and the prophets say … (“For Real”)

But there are ears to hear me in my softest voice,

There are hands to hold and point the way … (“A Healing in This Night”)

Over the years, Bob’s songs have been woven like bright threads into the fabric of my own life. When my grandmother died three months short of a hundred, my folk-singing sister Marilyn wasn’t sure what to perform at her funeral. Then one of Bob’s songs arrived by chance (or grace) in the mail. A friend had just come across “Alleluia, the Great Storm is Over,” and thought Marilyn would like it. It proved the perfect choice, heaven-sent, to sing our dear Nana home.

Sweetness in the air, and justice on the wind,

laughter in the house where the mourners had been.

The deaf shall have music, the blind have new eyes,

the standards of death taken down by surprise.

In a very low-def 2010 video of Bob and friends singing the song in a Massachusetts coffeehouse, you can hear the audience jumping in with the chorus before Bob even sings a word. His lyrics were so deeply planted in their hearts, they could not keep silent.

Bob wrote a cantata on Christ’s Passion, performing it with musician friends every Good Friday at his home parish, St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church in Marblehead, Massachusetts. One of those songs, “Roll Away the Waters,” a rousing celebration of the Exodus, became a regular part of the storytelling portion of my creative Easter Vigils over the years. Here is Bob’s version.

And when we hear again the Annunciation story in Advent, it’s time for Bob’s “Say Yes,” an artfully succinct summary of spirituality’s essence: receptivity and consent. Here’s a version I did during the pandemic for one of my church’s worship streams:

And whenever I need serious picking up, I’ll play “A Healing in This Night.” Here’s a fine version by Annie Patterson and Peter Blood:

“I always think of Bob as if Jefferson and Thoreau had picked up acoustic guitars and gotten into songwriting. There are touches of Mark Twain and Buddy Holly in there, too.” — Tom Paxton

Bob’s songs, and his spirit, are deeply rooted in American tradition—musically, culturally, politically. He sang on radio shows like Prairie Home Companion and A Mountain Stage, and traveled down many roads to perform in festivals, coffeehouses, churches and living rooms. His songs are imbued with the questions, dreams, struggles and shadows of American life. Even the hardest times are seen with a measure of possibility and redemption.

But in recent years he and his wife Joan saw the country they loved disintegrating into madness and rage. Feeling that the United States was becoming unsafe, and mindful of those who waited too long to exit Nazi Germany in the 1930s, Bob and Joan emigrated to Guatemala in September. They were barely into their second month in a new land when Bob was hit by a speeding motorcycle while crossing a road. Yesterday, October 16, a few days after surgery to repair the damage, he died in hospital of a heart attack. He was 78.

What can you do with your days but work and hope,

Let your dreams bind your work to your play.

What can you do with each moment of your life

But love till you’ve loved it away?

When the news of Bob’s death reached me around midnight, it hit hard. I lit a candle before an icon of the Theotokos, and picked up my guitar: “Thanksgiving Eve,” of course, “Alleluia, the Great Storm is Over,” and “A Healing in This Night.” I imagined people far and wide were doing the same—joining our voices with the whole company of heaven, as we say at mass.

Give rest, O Christ, to your servant

with your saints,

where sorrow and pain are no more,

neither sighing,

but life everlasting.

As for the song which saved that Harvard theologian’s life years ago, let Bob have the last word:

For more information on Bob Franke’s life and music: https://bobfranke.com