This is the third in a series of posts responding to the alarming events in Minneapolis. It may be the most arcane, of interest only to worship planners and storytellers. I usually try to write posts of more general interest, but my long experience as a liturgical creative and biblical storyteller impels me to set this down, for what it’s worth, as a small personal contribution to the ongoing efforts of the faithful to resist public malice and hold fast to the good with all the means at our disposal.

In evil times such as these, how can churches be faithful to the Baptismal Covenant to “persevere in resisting evil … seek and serve Christ in all persons … strive for justice and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human being”? In recent weeks, we have seen many clergy and laity adding their voices and bodies to the resistance against tyranny and cruelty in Minneapolis, and to the increasingly dangerous work of loving our neighbor and protecting the vulnerable.

As a longtime liturgist, I find myself wondering how—and to what degree—our worship gatherings, in addition to our witness in the public square, might themselves be responsive to what is happening around us—and inside us—during America’s current authoritarian nightmare. Prayer and preaching are two vital ways, and I have given some striking examples in my two previous posts, White House Brutality (prayer as a “refusal to consent to an unredeemed world … It breaks the silence, awakens the passive, and cultivates action, both human and divine.”) and Murder in Minneapolis (featuring one priest’s prophetic sermon, forged in the crucible of tyranny and protest).

Singing is also a powerful weapon against evil and its sad progeny—discouragement, fear and despair. It’s been said that the Civil Rights movement succeeded in part because it had a great soundtrack. Its stirring adaptations of black spirituals, sung not only in the marches but also in the jails, kept voices high and spirits strong. As they say, the people united will never be defeated. And nothing unites like communal singing. The resistance to American fascism is taking this to heart as collective song becomes once again a vital part of public protests.

Prayer, preaching and singing are all powerful ways to say yes to God and no to evil. And to that list I would add the telling of our sacred stories. Creative engagement with Scripture deserves equal attention as a means to lift up our hearts and shine the light of hope against the darkness. Week after week, year after year, Christians tell formative stories of sin and redemption, strife and reconciliation, despair and hope, losing and finding, oppression and liberation, death and resurrection. Then the preacher strives to connect those biblical stories with our own lives and times. But what if we were to make those connections not just in our homiletic reflections following the stories, but in the storytelling act itself?

As a young priest in Los Angeles during the Vietnam War, I staged a dramatized version of Jesus’ parable of the Unforgiving Debtor for an experimental eucharist. The man whose debt was very small was a draft resister, thrown into prison by an angry creditor dressed as Uncle Sam. That creditor was then reminded of the immensity of his own debt, illustrated by projected images of the atrocious violence in Southeast Asia.

Such a pointed retelling of Scripture might be too edgy for typical Sunday worship, but there are times when biblical stories really want to be heard in fresh and compelling ways. Holy Week 2026 can be a great opportunity to do that. How might worship planners think creatively about the Paschal journey from death to life in the context of our current experience of state-sponsored hate and violence?

The next No Kings march is scheduled for March 28, the day before Palm Sunday. How will it feel to reenact Jesus’ provocative entry into Jerusalem after millions of us will have shouted our own hopeful hosannas in the streets of America? What will be in our hearts on Maundy Thursday when our beautiful feast of loving one another concludes with the arrest our Lord by armed thugs? And when we come to the foot of the cross, will we see the God who not only shares our present suffering but also transforms it, making a Way where there is no way?

I love the traditional Scriptural texts for the Holy Week rites which take us on the Paschal journey from death into life. As containers for all the thoughts and feelings we bring to that journey, especially in times of immense public distress, they need no inventive retelling. They will be heard in fresh ways simply by virtue of what is in our minds and in our hearts throughout Holy Week 2026.

But when the sun goes down on Holy Saturday, and the Great Vigil of Easter begins to transport us from the world of sin and death into the realm of light and life, the world of the past is gone, and it is time to let imagination flourish, that we may find our own struggles and hopes vividly enacted in the performance of biblical narratives.

At the Easter Vigil, which I take to be the molten core of Christian worship, it is critical to experience those stories as if they are happening to us. We need to feel ourselves delivered from the flood of chaos and liberated from bondage to the powers-that-be. The dry bones of our damaged hopes need to rise again and inhale the breath of the Spirit. As the ancient Exultet chant declares at the outset of the liturgy,

How holy is this night, when wickedness is put to flight, and sin is washed away. It restores innocence to the fallen, and joy to those who mourn. It casts out pride and hatred, and brings peace and concord.

What does it take to do the Vigil stories justice? Well, it takes time and effort, a creative team, prayerful engagement with the stories, and openness to the Holy Spirit. Before offering a few tips for your own Vigil storytelling, let me give some examples from a Vigil I curated last year, as described in my April 2025 blog post, “For God so loved our stories”—Tales from the Easter Vigil:

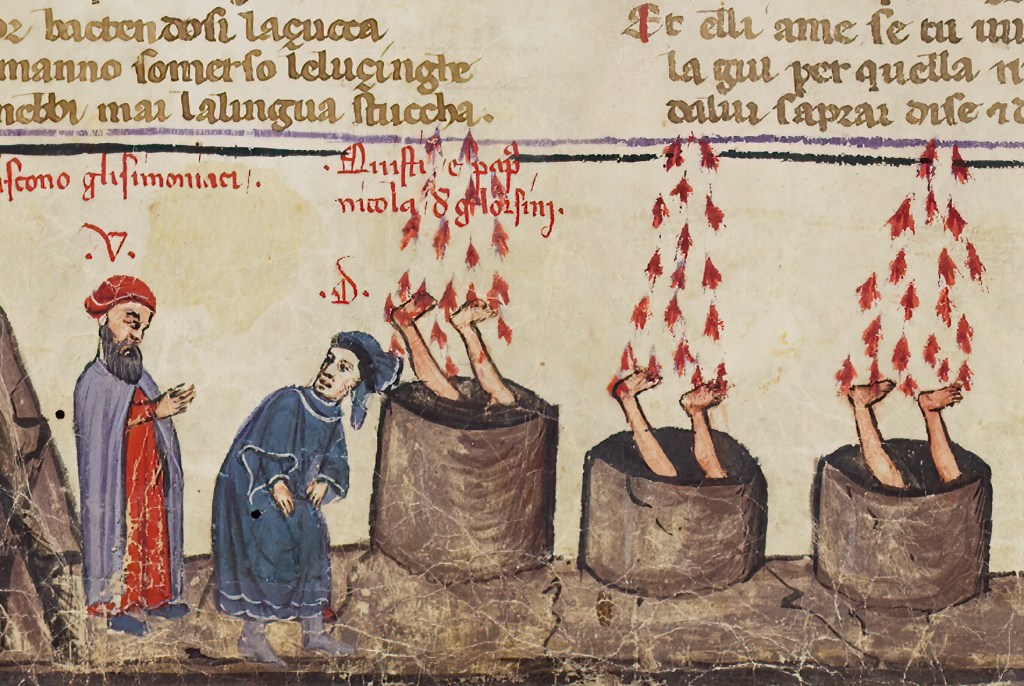

The Red Sea: Noirish projected images (from Bela Tarr’s bleak film, Werckmeister Harmonies) show anonymous figures shuffling through an imprisoning corridor, while dancers on the stage express the experience of oppression with their bodies. An offstage narrator explains:

Three thousand years ago, in the land of Egypt,

there were people who had no name.

They were the faceless many,

exploited by the powerful,

forgotten by the privileged: slaves, immigrants, the poor,

the homeless, the vulnerable, the invisible, the outcast.

Then dismissive terms for the oppressed appear on the screen in stark animated graphics: Not like us … worthless … horrible people … trash … less than human. More images of “the faceless many” are shown as the dancers continue, until an offstage choir sings a verse of “Go down, Moses.”

Suddenly, the divine breaks into this dark world: the screen flashes red, and we see the words from Psalm 68 that are always used in Orthodox Paschal liturgies:

Let God arise!

Let the foes of Love be scattered!

Let the friends of justice be joyful!

Then a song from the Civil Rights movement fills the room: “They say that freedom is a constant struggle … Oh Lord, we’ve struggled so long, we must be free.” The dancers’ bodies shift from oppression to liberation, while the screen shows powerful footage of crowds on the march for justice. As we hear a dub track with a repeated phrase by Martin Luther King, Jr.(“We cannot walk alone!”), the dancers begin their own march across the stage to the “Red Sea,” where they halt while the narrator declares:

This too is a creation story:

On this day, God brought a new people into existence.

On this day, God became known as the One who delivers the oppressed,

the One who remembers the forgotten and saves the lost ,

the One who opens the Way through the Sea of Impossibility,

leading us beyond the chaos and the darkness into the Light.

When the world says No, the power of God is YES!

As the dancers, joined by a small crowd of others, begin to cross the Sea, the choir (offstage) sings Pepper Choplin’s moving anthem, “We are not alone, God is with us …” After the song, a bidding to prayer begins:

Pray now for the conscience and courage

to renounce our own complicity

in the workings of violence, privilege and oppression.

Pray in solidarity with all who are despised, rejected,

exploited, abused, and oppressed.

Pray for the day of liberation and salvation.

The Fiery Furnace: This story from the Book of Daniel is borrowed from the Orthodox lectionary for the Paschal Vigil, and its humor (yes, the Bible can be funny) provides some comic relief after the Red Sea. The story’s mischievous mockery of a vain and cruel king, outwitted in the end by divine intention, feels quite timely. The idol shown on the screen is a golden iPhone, which will be destroyed by a cartoon explosion from Looney Tunes. The humorously tedious repetition of the instruments signaling everyone to bow is performed with the following (admittedly unbiblical) instruments: bodhran, bicycle horn, slide whistle, chimes, train whistle, and Chinese wind gong. The Song of the three “young men” in the furnace is recited by three women in an abbreviated rap version. At the end, the cast of twelve exit happily, singing the old Shape Note chorus, “Babylon is fallen, to rise no more!”

Then we give thanks “for the saints who refuse to bow down to the illusions and idolatries of this world” and pray for “the grace and courage to follow their example, resisting every evil, and entrusting our lives wholeheartedly to the Love who loves us.”

Valley of Dry Bones: Unlike the embellished retellings of the other stories, this one sticks closely to the biblical text, but is delivered in a storytelling mode by a single teller (me) in a spooky atmosphere of dim blue light. The voice of God is a college student on a high ladder. The sound of the bones joining together is made by an Indonesian unklung (8 bamboo rattles tuned to different pitches). When the story describes the breath coming into the lifeless figures sprawled across the valley, I get everyone in the assembly to inhale and exhale audibly a few times so that we can feel and hear the spirit-breath entering all of us. Then I move among them, bidding one after another to rise until everyone is standing, completing the story with their own bodies: the risen assembly itself becomes a visible sign of hope reborn.

Many churches don’t do the Easter Vigil, and of those that do, all too few give it proper attention as the richest and most luminous liturgy of the entire year. It requires a lot of preparation, effort and energy at the end of a very labor-intensive week. It also involves a long-term project of educating a congregation to understand the Vigil as the preeminent Easter rite.

You can celebrate the Resurrection gloriously on Sunday morning, but if you want to experience Resurrection in a kind of Christian dreamtime, come to the Vigil as well. And if you are in a community which already knows the unique power of the Vigil experience, I encourage you to explore the potential of its stories to empower our bodies and restore our souls in this dark and dangerous age.

If you are not part of a community that does the Easter Vigil, I thank you for reading this far anyway. But if you are in a position to shape a creative Vigil, here are some suggestions to get you started.

You may want to begin with just one or two stories. Find the creatives in your community and form a team to study the texts and discern what they are trying to say now. And think about the connections they make with our lives and our society. For example, footage from the Minneapolis protests could be part of the Red Sea saga, or the king’s ruffians throwing their victims into the fiery furnace could be dressed like ICE agents.

Decide for each story whether to use simple storytelling (one or more voices, scripted or retelling freely) or more theatrical means (scripts, actors, visual design, visual media, singing, musical score, sound effects, etc.). Think about ways to involve children (e.g., animals on the ark, or part of the Red Sea march to freedom) and even the whole assembly, through singing or collective reading, like a Greek chorus, of projected words on a screen. Involving as many people as possible in creating and performing the stories bolsters both attendance and enthusiasm. Play with ideas, images and words until the stories take shape. Then provide sufficient time for learning lines and rehearsals.

Ideally, the Story Space will be separate from the worship space. A parish hall is usually more flexible than a church interior in terms of seating and a stage area. If there is a screen or a large white wall, large images can be projected. Strings of party lights on a dimmer and LED spotlights with variable colors are easy ways to restrict light to the stage area and establish the mood for each story. The other advantage of a separate Story Space is that a liturgy conducted in a sequence of spatial locations underscores the Vigil as a journey—from the New Fire outside to the Story Space to the font to the altar and finally back into the world.

And let each story be followed by an appropriate song (I use both folk music and contemporary songwriters to fit the relaxed spirit of “tales around the sacred campfire,” in contrast to the chant and hymnody in the church portion of the liturgy). Then comes a bidding to prayer, summarizing the themes of the particular story.

Let me close with the bidding I wrote to follow The Valley of Dry Bones. It expresses everything I want to say about the liberating power of our stories to resist evil, proclaim hope, and lift up our hearts:

Dear People of God: There are those who tell our story as a history of defeats and diminishments, a narrative of dashed hopes and inconsolable griefs. But tonight we tell a different story, a story that inhales God’s own breath and sings alleluia even at the grave. By your baptism, you have been entrusted with this story, to live out its great YES against every cry of defeat.