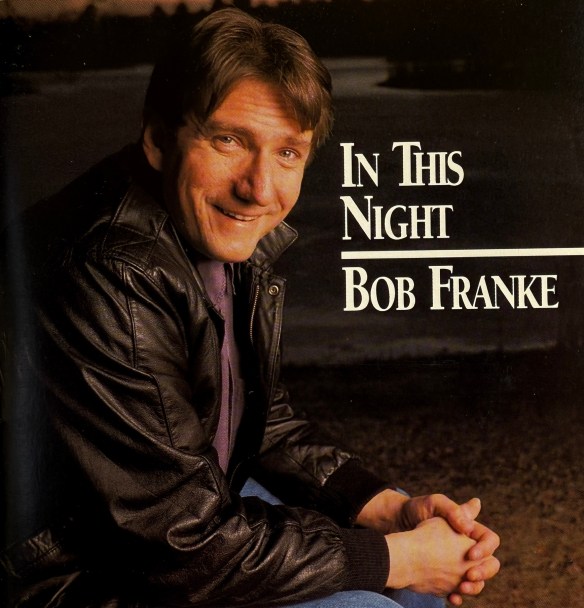

There within a stable, the baby drew a breath:

There began a life that put an end to death.

— Bob Franke, “Straw Against the Chill”[i]

In the dark days of 1943, Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane wrote the most melancholy Christmas song I know, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” It made its debut in the 1944 film, Meet Me in St. Louis, when Judy Garland sang it to cheer up her little sister. Their father had taken a job in New York, and the world they knew was about to end. The fact that it was Christmas—their last Christmas in St. Louis—only intensified their sense of loss. As the sisters gaze down from an upstairs window at the family of moonlit snow figures in the front yard, Garland, her moistened eyes seen in gorgeous Technicolor close-ups, delivers the song.

The film’s director, Vincente Minnelli (who would marry Garland the next year), thought the original lyrics too depressing, so he told the writers to make some changes. The line, “It may be your last / Next year we may all be living in the past,” became “Let your heart be light / Next year all our troubles will be out of sight.” But that did little to stop the tears of homesick soldiers viewing the film in distant war zones. In 1957, Frank Sinatra requested another change when he included the song on his holiday album, A Jolly Christmas. He asked Hugh Martin if he could “jolly up” the lyrics a bit more. Thus “until then we’ll have to muddle through somehow,” became “hang a shining star upon the highest bough.” Even so, the tune’s slow pace and moody melody have continued to suffuse the song with the seasonal melancholy which for some is the shadow side of Christmas cheer. If you’re feeling alone, sad, lost, anxious, or afraid, it’s hard to share in the holiday spirit. When your personal world—or our public world—lies in darkness, how do you “let your heart be light?”

A few centuries ago, Turlough O’Carolan, the blind harper and last of the Irish bards, was sitting in a tavern with his friend, the poet Charles McCabe, who said, “Your music, sir, is grand and lovely stuff; but it’s too light-hearted. This is a dark time we live in, Mr. Carolan, and our songs should reflect that.” The harper replied, “Tell me something, McCabe. Tell me this: Which do you think is harder—to make dark songs in the darkness, or to make brilliant ones that shine through the gloom?” [ii]

For the last half-century, I have gathered instrumentalists, singers and friends to lighten up the long night with carols and wassails from seven centuries and a dozen countries. “The Praise of Christmas” sums up the spirit of these evenings:

This time of the yeare

Is spent in good cheare;

Kind neighbors together meet

To sit by the fire

With friendly desire

Each other in love to greet;

Old grudges, forgot,

Are put in the pot,

All sorrowes aside they lay;

The old and the yong

Doth carol their song

To drive the cold winter away.

The old tune is appropriately vigorous, and the lyric by Thomas d’Urfey (1653-1723) is from his aptly titled songbook, Pills to Purge Melancholy. We do sing our share of quiet songs (“Hush! Hush! See how the child is sleeping.”), as well as wistful and mysterious carols in minor keys and medieval modes. But the predominant note is one of joy and wonder. As William Morris declared in his Victorian carol, “Masters in This Hall,”

Christmas is come in

And no folk should be sad.

Of course, no one should, but many are. Even in the best of times, there’s going to be some sadness in the room. As Henry Nouwen said, “No one escapes being wounded.” So we don’t sing our carols expecting present reality to be suddenly freed from every sorrow. But singing touches and heals the mind and heart, offering relief and comfort to “those who sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death” (Luke 1:79). As Robert Burton insisted in The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621), music is “the sovereign remedy against despair and melancholy … a “tonick to the saddened soul.” And W.E.B. DuBois, writing in the last century about “The Sorrow Songs” of African-American spirituals, said that “they grope toward some unseen power and sigh for rest in the End.” In other words, even laments can be agents of hope. As DuBois put it,

“Through all the sorrow of the Sorrow Songs there breathes a hope—a faith in the ultimate justice of things. The minor cadences of despair change often to triumph and calm confidence.” [iii]

Compared with the emotional and social realism of black spirituals, what can we say about Christmas carols? Do they have a similar healing power? Or is their bright spirit in denial of the “two thousand years of wrong” which have followed the miraculous “midnight clear” in Bethlehem? Can we who dwell in the shadow of death still sing about joy and peace with whole-hearted conviction? As the Psalmist wondered, “How can we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” And yet, we sing. We sing because carols gladden the heart and bring us together. And we sing because carols are eschatological anticipations of God’s unfolding future. They don’t put an end to our troubles, but they give us a foretaste of glory, reminding us that we belong not to what is dying, but to what is being born.

Gabriel’s message does away

Satan’s curse and Satan’s sway;

Out of darkness brings our Day:

So behold,

All the gates of heav’n unfold.

In my Los Angeles days, I’d rise at 4 a.m. at the Winter Solstice, toward the end of the longest night, and drive to a peak above the ocean in the Santa Monica Mountains, where I could see the newborn sun rise over desert peaks 100 miles to the east. But in the Northwest where I live now, a winter sunrise can be a rare sight. This December’s relentless stretch of rain and thick clouds seemed to doom my chances. Still, I awoke at sunrise out of habit, and when I glimpsed the Douglas firs on a hilltop ablaze with fiery light. I jumped in my car and raced to the edge of the island to see the gloom on the run. It was the perfect Advent sign: The people who have lived in darkness, and in the shadow of death (umbra mortis, as the 8th-century O antiphons put it), have seen a great light.

Did it matter that by the end of the day the sun had vanished and rain was pouring down? Not at all. I had received the gift of light as an eloquent sign: Don’t forget what you have seen. Remember hope.

Dear reader, I wish you a most blessed and merry Christmas. Let your heart be light!

[i] Bob Franke’s “Straw Against the Chill” (Telephone Pole Music) is a beautiful contemporary carol. I recently posted a tribute to Bob’s legacy. You can listen to the song here:https://youtu.be/N-VXxACc4U4?si=Xn2O1qZgr01O5ckr

[ii] I heard this story in the California Revels CD, Christmas in an Irish Castle (2001).

[iii] The Nouwen, Burton, and DuBois quotes are from Kay Redfield Jamison’s powerful and moving book, Fires in the Dark: Healing the Unquiet Mind (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003). It is a fascinatingly documented and beautifully written treatise on the spiritual and imaginative dimensions of healing body and soul.