Survivors of the twentieth century, we are all nostalgic for a time when we were not nostalgic. But there seems to be no way back. — Svetlana Boym

In the Second World War, Paris was spared the physical destruction suffered by so many other cities. It surrendered without a fight to the Germans, some of whom cherished fond memories of living there as students before the war. And the Nazi government, believing itself to be the future of Europe, had no desire to smash such a cultural icon into rubble. It coveted the prestige of the City of Light for itself.

The example of a city physically unchanged while suffering the invasive presence of a hostile power may have something to teach Americans, whose own cities face threats of military occupation by the dictatorial regime in Washington, D.C.. When I read Ronald C. Rosbottom’s riveting study, When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944, I could not help noticing some striking parallels to our own “les annes noires” (the dark years).

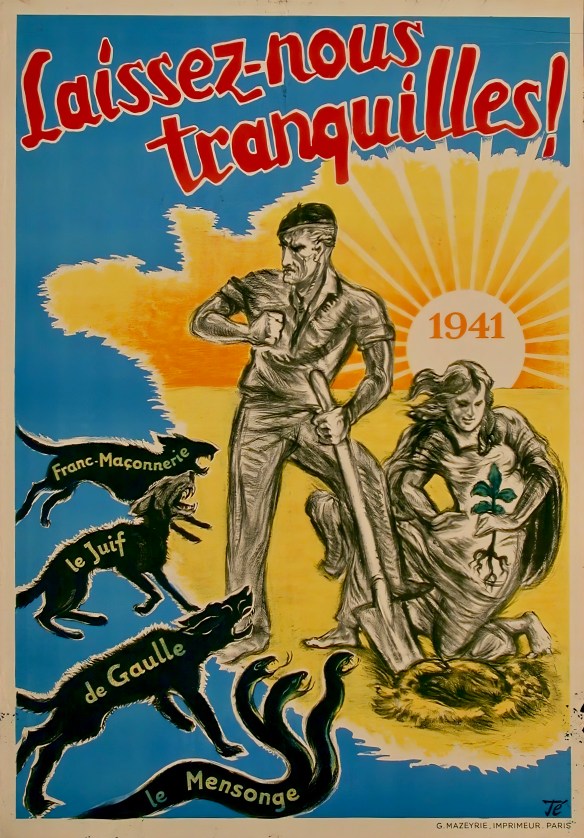

The radical right in the United States likes to dismiss any comparisons between Nazis and themselves as hyperbolic and slanderous, and it is fair to argue that their own movement may never go as far as the Nazis did. It’s too early to tell. But they’ve made a good start: terrorizing the vulnerable with the ICE-capades of masked thugs, demonizing and disappearing “aliens” and “enemies,” attacking the judicial system, vitiating the free press, purging opposition in the military and civil service, compelling the complicity of corporate leaders, seducing gullible and idolatrous evangelicals, and corrupting everything they touch. Fueling it all is their ceaseless stream of lies and propaganda. As Hannah Arendt warned in the aftermath of World War II:

“If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that you believe the lies, but, rather, that nobody believes anything any longer. And the people that no longer can believe anything cannot make up its mind. It is deprived not only of its capacity to act, but also of its capacity to think and to judge. And with such people, you can then do what you please.” [1]

Much more could be said about that, but for now our subject is the occupation of Paris. When the Germans entered the French capital in June, 1940, they encountered no resistance. Parisians were disheartened by the swift collapse of the French army and unhappy to see so many German soldiers and officials suddenly walking their streets and filling their cafés, but what could they do? Many fled Paris before the troops arrived, but most of those returned when they saw how “normal” things seemed. Daily life was not radically affected at first, and few thought the occupation would last such a long time. There was shame in defeat, certainly, and resentment of a foreign presence, but for a time passivity and resignation kept the anger of many Parisians’ turned inward.

There was a degree of make-believe on both sides. German soldiers were instructed to be polite. If someone drops a package on the sidewalk, pick it up for them. Parisians tried not to reciprocate any such acts of kindness, but to practice what they called Paris sans regard (“Paris without looking”). As much as possible, pretend the Germans don’t exist. Over time, this depersonalization would create a great sense of loneliness among the occupiers. As for Parisians, the make-believe minuet with the occupiers was both wearying and fragile. As one young man wrote in his journal,

“In spite of oneself, one dreams, laughs, and then falls back into reality, or even into excessive pessimism, making the situation more painful.” [2]

A month after the Germans arrived, “Tips for the Occupied,” a mimeographed flyer, began to appear in apartment mailboxes. “Don’t be fooled,” it warned. “They are not tourists … If one of them addresses you in German, act confused and continue on your way … Show an elegant indifference, but don’t let your anger diminish. It will eventually come in handy …” [3]

The sense of normality didn’t last. The restaurants, cabarets and cinemas remained crowded, but when audiences began to boo and jeer at Nazi newsreels, the houselights would be turned up. People lost their courage when they could be easily spotted. Parisians also learned to be careful about saying the wrong thing in a café. Neighbors began to denounce each other to the authorities. Singing “The Marseillaise” in public became a punishable crime.

As the Occupation dragged on, the sense of dépaysement (“not feeling at home”) began to wear on the soul. Historian Jean-Paul Cointet describes the condition in his 2001 study of wartime Paris:

“The Parisian now knows the condition of being ‘occupied’ in a city that does not belong to him anymore and that offers him the schizophrenic images of an environment suddenly foreign to his gaze. Constraints and humiliations, restrictions and punishments accompany this disorientation and the upending of daily routine.” [4]

The narrowing of space—both physical and psychological—became increasingly oppressive, as Rosbottom notes:

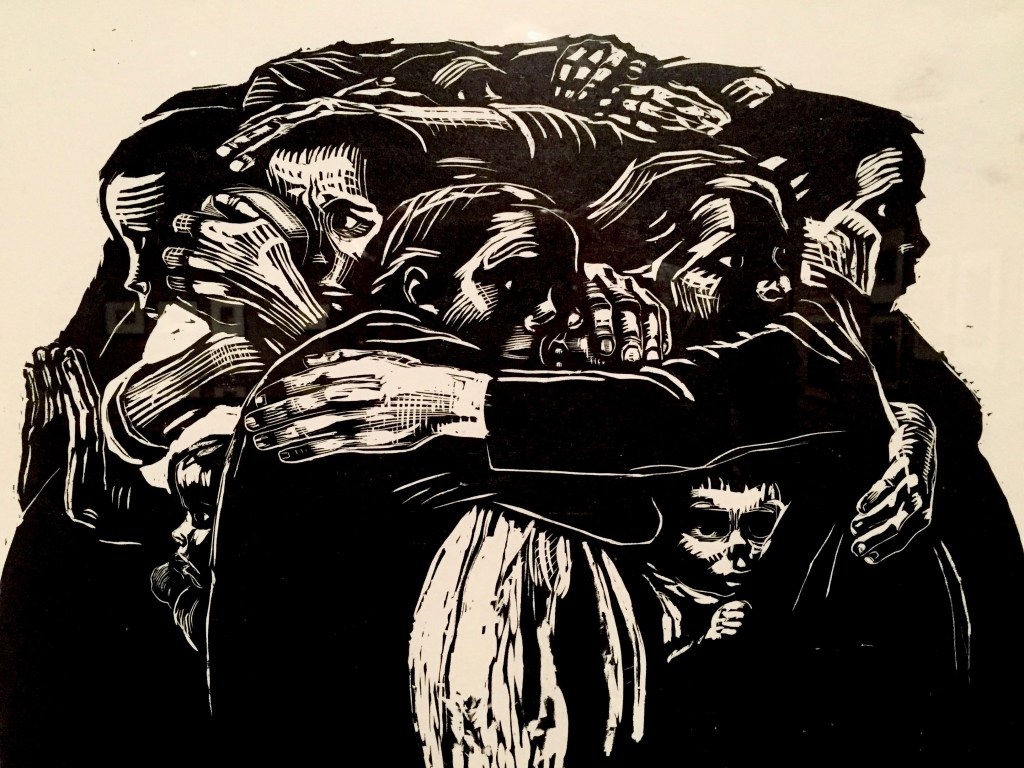

“Whether because of the sight of German uniforms, the closed-off streets, the insufficient nourishment, the cold winters, crowded transportation, long lines—or just the suffocating feeling of being suspicious of one’s acquaintances, neighbors, or even family—the city seemed to be contracting, closing in on Parisian lives, as the Occupation dragged on.” [5]

By the bitterly cold winter of 1941, life just got harder. Shortages of food and coal brought malnutrition and sickness, especially among the lower classes. French police, willing agents of Nazi oppression, started to raid neighborhoods known for Jewish or immigrant populations. At first, Parisians in uninvaded neighborhoods could close their eyes and swallow the lie that the authorities were simply trying to control immigration and prevent terrorism.

However, by mid-1942, rumors of the “final solution” began to reach Paris, and the mass roundups of Jews in France became impossible to ignore. “[Most Parisians] certainly did not know of the plans to deport them to their deaths,” writes Rosbottom, “but to their deaths they went: the last, sad convoy to carry children, three hundred of them, left Drancy for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 … The final transport of adult deportees left on August 17, a week before Paris would be liberated.” [6]

Ernst Jünger, a cultured writer serving as a captain in the occupying Wehrmacht, kept a journal of the Occupation. In July 1942 he wrote:

“Yesterday some Jews were arrested here in order to be deported—first they separated parents from their children, so firmly that one could hear their distressed cries in the streets. At no moment must I forget that I am surrounded by unhappy people, humans experiencing the most profound suffering. If I forgot, what sort of man or soldier would I be?” [7]

Jünger may have shed a tear, but he continued to serve as a loyal employee of the Nazi death industry, whose business, as Hannah Arendt so bluntly noted, was “the mass production of corpses.” [8]

Hélène Berr also kept a diary, from Spring, 1942 until Spring, 1944. As a young Jewish woman, she tried to keep terror at bay by imagining herself in a Paris magically untouched by the darkness. A student at the Sorbonne, she copied out verses of Keats to calm her soul, and took refuge in her friendships. She made frequent walking tours of the city she loved, as if to reclaim possession of Paris from the occupiers who made her wear a yellow star, the mark of social exile.

In April of 1943, Hélène wrote:

“I’ve a mad desire to throw it all over. I am fed up with not being normal. I am fed up with no longer feeling free as air, as I did last year. It seems that I have become attached to something invisible and that I cannot move away from it as I wish to, and it makes me hate this thing and deform it … I am obliged to act a part … As time passes, the gulf between inside and outside grows ever deeper.” [9]

As Rosbottom notes, personal accounts of the period recall “the sound of police—French police—beating on the door” as their “most vivid aural memory.” [10] In March 1944, that percussive death knell sounded in the Berr’s apartment. Hélène, along with her parents, was arrested, but she managed to slip her journal to their cook before the police barged in. Three weeks later the Berrs were on a train to Auschwitz. They never returned. Hélène’s beloved Paris would be liberated five months later.

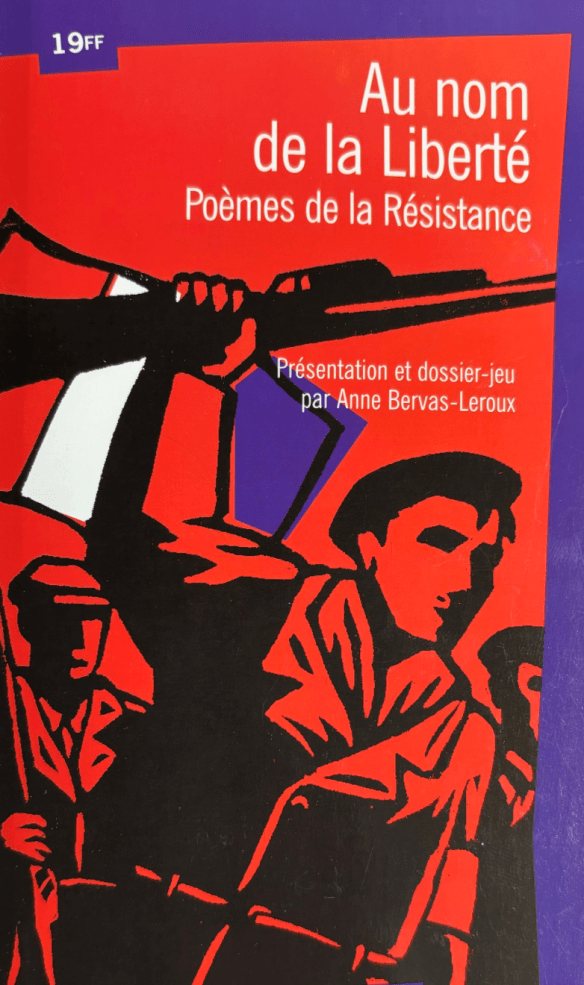

There were many forms of active resistance to the Nazis in France, but the number of French patriots who risked their own lives was relatively small—less than 2% of the population. The threat of death and brutal reprisals was too daunting for most. For a visceral immersion in the anxious milieu of the French Resistance, watch Jean-Pierre Melville’s haunting film, Army of Shadows. Critic Amy Taubin’s summary of the film feels descriptive of wartime Paris: “Elegant, brutal, anxiety-provoking, and overwhelmingly sad.” [11] One resister recounted his experience in an interview decades after the war:

“Fear never abated; fear for oneself; fear of being denounced, fear of being followed without knowing it, fear that it will be ‘them’ when, at dawn, one hears, or thinks one hears, a door slam shut or someone coming up the stairs. Fear, too, for one’s family, from whom, having no address, we received no news and who perhaps had been betrayed and were taken hostage. Fear, finally, of being afraid and of not being able to surmount it.” [12]

As I read Paris in the Dark, I had to wonder: Is this America’s future? For many of us (to borrow a line from Bob Dylan), “It’s not dark yet—but it’s getting there.” Daily life —for now, at least—goes on pretty much as usual. But for some of our neighbors, the darkness has definitely arrived. The military occupation of cities. The terrifying knock on the door. The roundups, disappearances, and concentration camps. The shamelessly gleeful cruelty. Demonization, bigotry and hate. The repression of customary freedoms. The criminalization of dissent. The collapse of legal safeguards. The willing complicity of the powerful with the enemies of life.

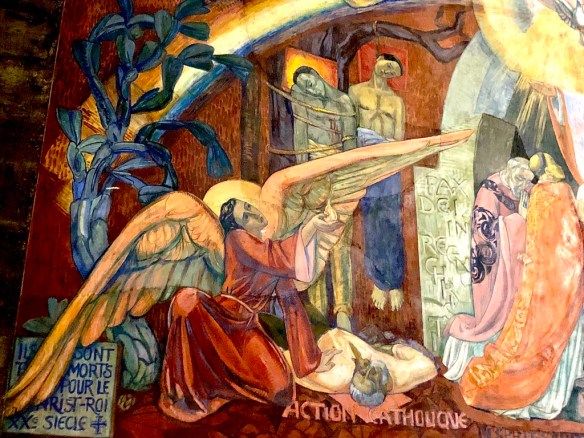

I am not without hope. Seven million protesters took to the streets on No Kings Day. Then large majorities voted against America’s reign of madness. And regardless of any political swings of the pendulum, I believe that resurrection continues to plant its seeds among the blind sufferings of history. But the oligarchs and fascists won’t go quietly. On the day after the recent election, the Episcopal Daily Office included this timely verse from the Book of Revelation:

Woe to the earth and the sea,

for the devil has come down to you

in a great rage,

because he knows that his time is short. (Rev. 12:12)

This Scripture feels ripped from the headlines. We know that satanic rage all too well. It has sickened our country, and we struggle to keep it out of our own hearts. May its time be short. In the meantime, the woes are not done. God’s friends have their work cut out for them. Believe. Resist. Endure.

And guard your heart against the demons of dejection and despair. After Trump’s election in 2016, I suggested seven spiritual practices for the time of trial: pray, fast, repent, prophesy, love, serve, hope. Click the link for the details. Nine years later, these practices are more necessary than ever, and I encourage you to share the link as a small act of resistance.

Finally, don’t be in love with outcomes. Divine intention takes mysterious forms, and should not be confused with our own plans. Let us heed the counsel of two twentieth-century saints who were deeply committed to holy resistance and well acquainted with its challenges and ambiguities. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, martyred in a Nazi prison in 1945, believed that we must always act with deep humility, shedding our presumptions about the part we play or the difference we make. Don’t fret about your success. Just be faithful to Love’s command:

“No one has the responsibility of turning the world into the kingdom of God … The task is not to turn the world upside down but in a given place to do what, from the perspective of reality, is necessary objectively, and to really carry it out.” [13]

And Thomas Merton, who forged a delicate balance between contemplation and activism, taught that right action is not a tactic but a persistent way of being, grounded in something deeper and more enduring than any of our consequences:

“The message of Christians is not that the kingdom ‘might come, that peace might be established, but that the kingdom is come, and that there will be peace for those who seek it.’” [14]

[1] Hannah Arendt, quoted in the PBS documentary, Hannah Arendt: Facing Tyranny (American Masters, 2025).

[2] Ronald C. Rosbottom, When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 (New York: Back Bay Books, 2014), 106.

[3] Ibid., 196-197. The flyer was produced by Jean Texcier.

[4] Ibid., 160.

[5] Ibid., 161.

[6] Ibid., 286.

[7] Ibid., 154.

[8] Hannah Arendt: Facing Tyranny.

[9] Rosbottom, 256.

[10] Ibid., 160.

[11] Amy Taubin, ”Out of the Shadows,” Criterion booklet for their 2010 Blu-ray release of Melville’s 1969 film.

[12] Rosbottom, 223, quoted from interviews with WWII resisters published in 2012.

[13] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, q. in Christiane Tietz, Theologian of Resistance: The Life and Thought of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press), 121.

[14] Thomas Merton, Turning Toward the World: The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Four, 1960-1963 (New York: Harper Collins, 1996), 188.