For he is our childhood’s pattern;

Day by day, like us He grew;

He was little, weak and helpless,

Tears and smiles like us He knew;

And He feeleth for our sadness,

And He shareth in our gladness.

— Cecil Frances Alexander, “Once in Royal David’s City”

My sisters and I each had an unusual childhood connection with the Nativity story. Our father, the Rev. James K. Friedrich, was the pioneer of Christian movie-making in America, and one of his first biblical films was Child of Bethlehem, produced in 1941. My sister Martha was a newborn child then, so she got to play the baby Jesus. Nine years later, my father made Holy Night, the first of a twelve-part series on the life of Christ. I was four years old at the time—much too old to get the leading role—so I was cast as a shepherd boy, entering the stable with several adult shepherds.

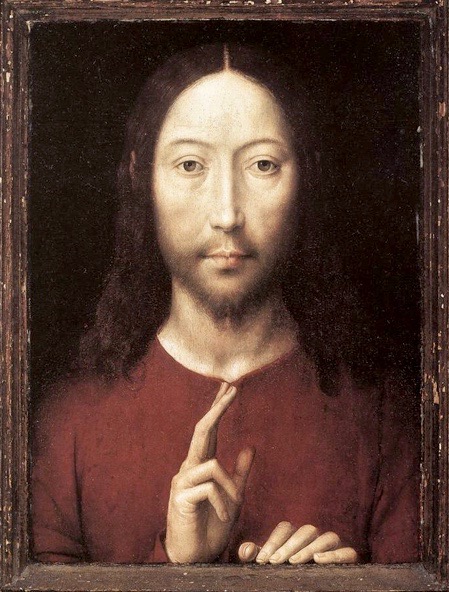

In the film, I have a dazed look on my face. I was literally blinded by the light on the Hollywood soundstage where the interiors were shot. Film stock in those days was not as light-sensitive as our camera phones. It required intense illumination to register a proper image. A big row of Klieg lights set up behind the manger threw such a blaze into my eyes that I could barely see the Holy Family. When I hear Luke’s gospel report that “the glory of the Lord shone all around” the shepherds, the indelible memory of those lights at Goldwyn Studios comes to mind.

My oldest sister, Marilyn, never played in a Nativity film. Hers was a more literal reenactment. In 1936, my parents had stopped in Jerusalem during their honeymoon. In those days, as today, there was violence in the land, and they were warned not to go down the hill to Bethlehem in a car, because cars were easy targets for snipers. It was safer to ride a donkey to the place of Jesus’ birth. My dad recorded their pilgrimage with his 16mm movie camera, and now, every Christmas, I can watch the footage of my mother riding a donkey to Bethlehem, pregnant with her firstborn child.

To Marilyn’s credit, she has never made any personal claims about her origins, but there is, I believe, gospel truth in our childhood memories. Each and every one of us is called to play our part in the Nativity story, but not merely as witnesses like the shepherds or pilgrims like the Magi. God was made flesh so that our own flesh, our own story, may birth the divine intention and the divine life.

You see, the Incarnation isn’t only a matter of God wanting to share our humanity, to make our humanness part of the divine experience. It also reveals God’s desire that we in turn become partakers of the divine nature.

St. John put it this way in his gospel:

To all who received the Incarnate Word, who believed in his name, the Word gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or the will of human beings, but of God (John 1:12-13).

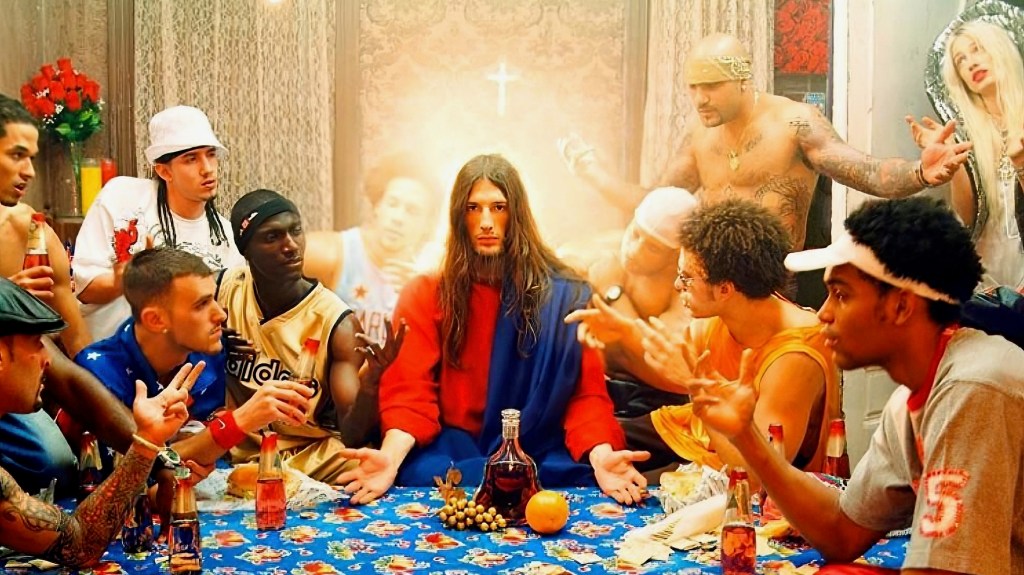

In the centuries that followed, this theme of theosis, or deification––becoming God-like––has pushed the envelope of anthropology by setting a very high bar for the definition of human potential.

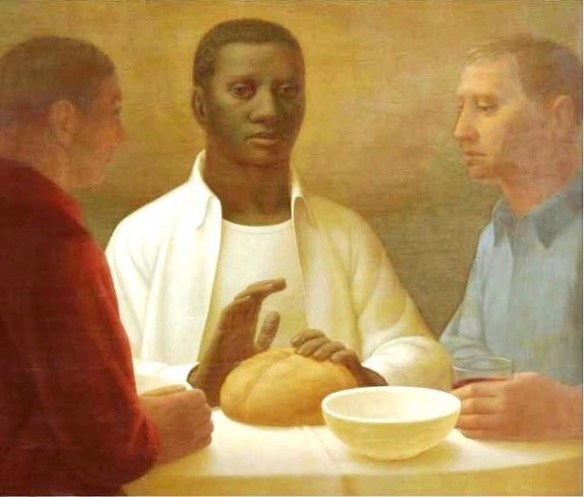

In the early church, Irenaeus said that “God became what we are, in order to make us what he is.” Athanasius was even more explicit about the consequences of Incarnation, saying that “God became human so that humans might become God-like.” God-like! Can we even imagine this in our own day, when we are assaulted incessantly by news of human depravity.

Martin Luther, perhaps surprisingly for someone so focused on the burden of human sin, said we were all called to be “little Christs,” and in a Christmas sermon he described the Incarnation as a two-way street: “Just as the word of God became flesh,” he said, “so it is certainly also necessary that the flesh may become word. . . [God] takes what is ours to himself in order to impart what is his to us.”

In the 18th century, some of Charles Wesley’s great hymns were almost shockingly explicit about our capacity to contain divinity.

He deigns in flesh to appear,

Widest extremes to join,

To bring our vileness near,

And make us all divine.

Heavenly Adam, life divine,

Change my nature into Thine;

Move and spread throughout my soul,

Actuate and fill the whole;

Be it I no longer now

Living in the flesh, but Thou.

In the 20th-century, whose atrocities left our confidence in human potential badly shaken, the Catholic contemplative Thomas Merton could still claim that we “exist solely for this, to be the place God has chosen for the divine Presence. The real value of our own self is the sign of God in our being, the signature of God upon our being.”

And after his famous epiphany at the corner of Fourth and Walnut in Louisville, Merton said, “It is a glorious destiny to be a member of the human race, though it is a race dedicated to many absurdities and one which makes many mistakes: yet, with all that, [God’s own self] glorified in becoming a member of the human race.

“I have the immense joy of being [a human person],” he continued, “a member of a race in which [God’s own self] became incarnate. As if the sorrows and stupidities of the human condition could overwhelm me, now that I realize what we all are. And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.”

Is this all this talk about divinization going too far? Could we really be walking around shining like the sun? Or at least have the potential for such glory, even if we’re not there yet? If the Nativity in Bethlehem means what I think it does, then the answer has to be yes.

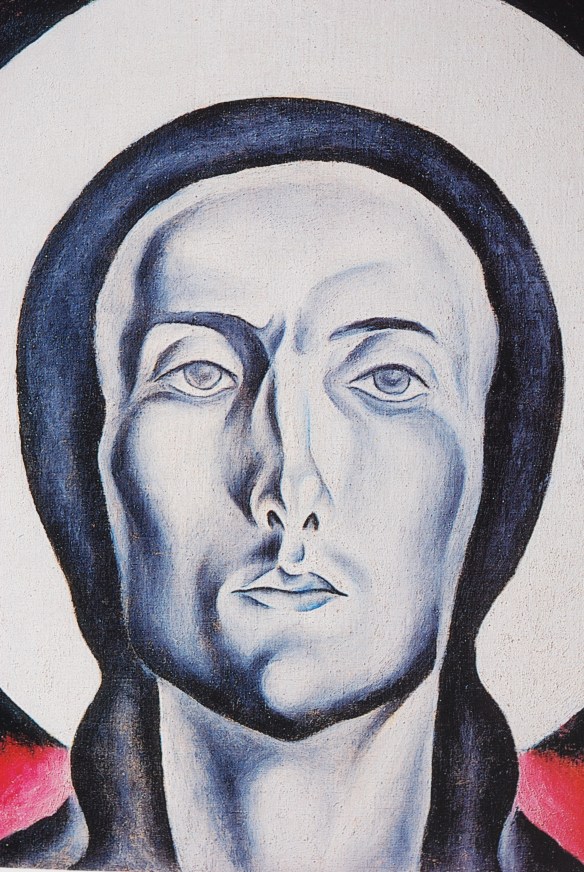

On that wondrous night in Bethlehem, our nature was lifted up as the place where God chooses to dwell. We may still be works in progress, but we are bound for glory. St. Paul believed this when he said that “all of us, with our unveiled faces like mirrors reflecting the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the image that we reflect in brighter and brighter glory” (II Cor. 3:18).

Another ancient theologian said, “As they who behold the light are within the light and partake of its brightness, so they who behold God are within God, partaking of God’s brightness.”

What happens in Bethlehem doesn’t stay in Bethlehem.

On the Winter Solstice over 40 years ago, I was flying across the San Fernando Valley into L.A.’s Burbank airport on a brilliant December day. The noonday sun was low enough in the southern sky to be reflecting its rays off the surface of swimming pools running along a line parallel to our flight path. There are so many pools in the Valley, and each one, as it was struck by the sun, exploded with an intense dazzle of white light. In rapid succession, tranquil blue surfaces were transformed into momentary images of the sun’s bright fire. For me, it was a vision pregnant with the Christmas promise.

“They who behold the light are within the light and partake of its brightness.” Our pale mirrors are made to contain the most impossible brilliance. And though we have turned away from the Light, the Light seeks us out. No matter how shadowy the path we have taken, the Light will find us, and fill us with divine radiance. That is our destiny, says the Child in the manger.

We may not feel capable or worthy or prepared to receive the Word into the flesh of our own lives, but it is what we were made for. Paradoxical as it may sound, partaking of divinity is the only path to becoming fully human.

A month before he died, Edward Pusey, a 19th-century English priest, wrote to a spiritual friend about our God-bearing capacity:

“God ripen you more and more,” he said. “Each day is a day of growth. God says to you, ‘Open thy mouth and I will fill it.’ Only long. . . The parched soil, by its cracks, opens itself for the rain from heaven and invites it. The parched soil cries out to the living God. O then long and long and long, and God will find thee. More love, more love, more love.”

Participating in divinity doesn’t mean having superpowers or being invulnerable. We won’t be throwing any lightning bolts. Just look at Jesus. His life tells you what “God-like” means. He was born in poverty and weakness, in a stable not a palace, and he lived a life of utter self-emptying and self-offering, giving himself away for the life of the world.

In a novel by the Anglican writer Charles Williams, a young woman goes to church with her aunt on Christmas morning. She is a seeker, not quite a believer, but as they sing a carol about the mystery of the Incarnation, she leans over and whispers to her aunt, “Is it true?” Her aunt, one of those quiet saints who has spent her life submitting to Love divine, turns to her niece with a smile and says simply, “Try it, darling.”

So if you want to try it, if you want to complete your humanity by partaking of divinity, there are many ways to do that. Weep with those who weep and dance with those who dance, the Bible says. Love God with all your heart, and your neighbor as yourself. Welcome the stranger, feed the hungry, free the captive. There are plenty of to-do lists out there. Here’s an excellent one from the Dalai Lama:

May I become at all times,

both now and forever:

A protector for all who are helpless.

A guide for all who have lost their way.

A ship for all who sail the oceans.

A bridge for all who cross over rivers.

A sanctuary for all who are in danger.

A lamp for all who are in darkness.

A place of refuge for all who lack shelter.

And a servant for all those who are in need.

May I find hope in the darkest of days,

and focus in the brightest.

My friends, Bethlehem is not a dream fading away into the past.

It is the human future.

And this is not the morning after.

It is the first day of the rest of our journey into God.

A sermon for Christmas Day at Saint Barnabas Episcopal Church, Bainbridge Island, Washington.