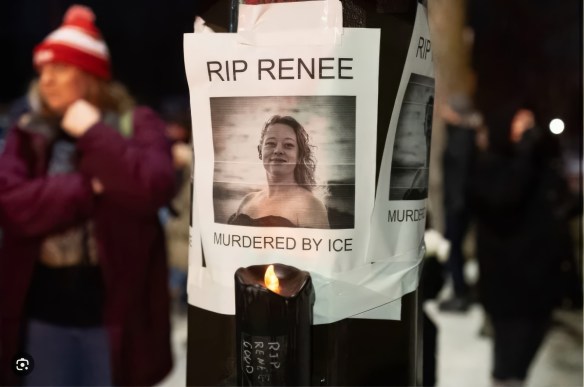

“It’s fine, dude, I’m not mad at you.” According to video allegedly taken by ICE agent Jonathan Ross, those were Renee Nicole Good’s last words, addressed directly to him, with a smile. Seconds later, Ross shot her in the face. Three times.

Ross didn’t murder her because his own life was being threatened. All the video evidence available so far contradicts that lie. Perhaps a serious investigation—if there ever is one—will uncover the details of his personal role in Renee Good’s death. But he did not act alone. The White House gave him the gun and, through its policies and its rhetoric, encouraged him to pull the trigger.

The fact that the murder of an American citizen was immediately condoned by the highest levels of government—and continues to be defended, without the slightest trace of remorse, as the right thing to have done—should be a Pearl Harbor or 9/11 moment for our country. If it isn’t, if it just further normalizes our national descent into evil and madness, then God help us.

The shocking brutality of Good’s murder is not the work of a single bad actor. It is the expression of national policy under Donald Trump, whose murderous cruelty, by his own admission, knows no bounds. As he made clear in a recent New York Times interview, he is accountable not to Congress, the courts, international law, common decency, or any other norms or considerations beyond the seething cauldron of impulse and rage going by the name of Donald Trump. His only limitation, he claims, is “my own morality, my own mind. Nothing else can stop me.”

Such malignant and dangerous narcissism invites comparison with C. S. Lewis’ chilling description of Satan:

“[He is] no longer a person of corrupted will,” but “corruption itself, to which will was attached only as an instrument. Ages ago it had been a Person; but the ruins of personality now survived in it only as weapons at the disposal of a furious self-exiled negation.” [i]

For more on the dis-ease and dis-order spawned by Trump’s furious negation, see my 2019 post, “The Worm That Gnaws the World”—Trump and the Problem of Evil.

Evil is contagious, and the toxicity level among the ruling powers has become so high that it never seems enough for Trump, or his collaborators and enablers, merely to initiate, condone and encourage acts of hatred and violence. They also have an insatiable compulsion to smear and assault their victims with absurd lies and vicious abuse.

Vice President J.D. Vance, a nominal Catholic who cares little for his church’s teachings, provides one of the most egregious examples of this shameless evacuation of human decency. He shed no tears for Renee Good, preferring to revel in making vicious and unfounded attacks. He congratulated her killer and warned the rest of us, in effect, that we too must obey or die.

Religious journalist John Grosso wrote a scathing rebuke to Vance’s despicable rhetoric in the National Catholic Reporter:

“The vice president’s comments justifying the death of Renee Good are a moral stain on the collective witness of our Catholic faith. His repeated attempts to blame Good for her own death are fundamentally incompatible with the Gospel.” [ii]

The violence done to Renee Good in Minneapolis is part of a virulent malignancy raging throughout our body politic, in both domestic concerns and our foreign policy. In defense of Trump’s imperial fantasies about Venezuela and Greenland, a Republican congressman epitomizd our sickness when he boasted that “the U.S. is the dominant predator … in the Western hemisphere.”[iii] In other words, it is the right of the rich and powerful to devour the poor, the weak, and the vulnerable. Resistance is futile, and punishable by death.

Well, we may not be quite there yet, but every day of silence or passivity moves us closer to a fascist nightmare. It is time to take on the urgency of the biblical prophets, as in the alarm sounded long ago by Joel in a text still read in the penitential rites of Ash Wednesday:

Sound the trumpet in Zion;

consecrate a fast;

call a solemn assembly;

gather the people.

Consecrate the congregation;

assemble the aged;

gather the children,

even infants at the breast.

Let the bridegroom leave his room

and the bride her canopy.Between the vestibule and the altar,

let the priests, the ministers of the Lord, weep.

Let them say, “Spare your people, O Lord.” (Joel 2:15-17)

Visiting an Episcopal church in California this past Sunday, I heard that same urgency in the Prayers of the People. After the formally composed intercessions from the Book of Common Prayer, the priest read handwritten petitions and thanksgivings submitted that morning by the assembly. There were lists of those who sought healing, compassionate pleas for those in need, and general longings for peace and justice. But there was also a notable number of prayers addressing the current outbreak of hatred and brutality.

We pray for all those unlawfully detained by ICE … for the family of Renee Good, and for the repose of her soul … for grace and healing in our nation, … for our children and grandchildren as they see our country changing … for all citizens and immigrants … and we give thanks for brave witnesses, and for the renewal of hope that loving acts inspire.

I was particularly struck by a petition asking our prayers for certain individuals with Hispanic names, followed by “and for all those who fear us.” That simple prayer made a bridge, however slight, across the void between “us” and “them.” And for one precious moment, its explicit hope for an end to fear and the beginning of reconciliation filled the church with the sweet fragrance of possibility

Prayer is a refusal to consent to an unredeemed world, and for people of faith it is foundational for an ethical existence. What St. Paul said about love applies equally to prayer. It “bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (I Cor. 13:7). It breaks the silence, awakens the passive, and cultivates action, both human and divine.

So don’t despair, or give in, or give up.

Look for the ones who are called

into the righteous flow

of prayer and action.

And join them.

[i] C.S. Lewis, Perelandra (1943).

[ii] John Grosso, National Catholic Reporter online, January 8, 2026: https://www.ncronline.org/opinion/ncr-voices/catholic-vice-president-vance-takes-social-media-justify-killing-renee-good

[iii] https://www.commondreams.org/news/andy-olges-greenland-predator