In my recent post, Walking St. Cuthbert’s Way (7/28/2023), I described my 100-kilometer pilgrimage walk to the Northumbrian coast, where I had my first glimpse of Holy Island, where Cuthbert had been prior and bishop in the seventh century. In this installment, I cross over the tidal flats to reach my goal and discover why I had come.

I’ve always been fascinated by the open-ended wanderings of the Dark Age Celtic monks. They journeyed without maps, trusting the way would be shown in due time. They got into little boats without oars or rudders, letting the wind and the currents be the agents of Providence. And where did they end up? Wherever it might be, they believed it was a place appointed for them by God. “The place of resurrection,” they called it. The place where they would meet Christ, the one “who knows you by heart.”[i]

But the arrival was, in a way, beside the point. The journey was the thing—the way of total abandonment and radical trust. Unlike ourselves, who think we already know who we are and where we should go, they traveled without preconception. In their eyes, you don’t know who you really are before you go on pilgrimage. Only the way of abandonment and unknowing will bring you home to your truest self.

“As a man dies many times before he’s dead,

so does he wend from birth to birth until, by grace, he comes alive at last.”

— Frederick Buechner, Godric [ii]

Holy Island is only a part-time island. When the tide goes out, you can walk across the exposed sands, or drive over the causeway. Pilgrims properly go on foot, timing their two-mile passage to coincide with low tide. You don’t want to be caught in the middle when the waters return, swallowed like the Egyptians of old. Yes, the Red Sea comes to mind here, and the river Jordan—those great baptismal archetypes of crossing over from bondage to freedom, old to new, death to life. As I took my first steps on the wet sand, I sang one of my favorite shape note hymns:

Filled with delight, my raptured soul would here no longer stay;

Though Jordan’s waves around me roll, fearless I’d launch away.

I am bound for the Promised Land …[iii]

I had brought some rubber beach slippers, thinking I might need a barrier against cold water or sharp objects, but the sand immediately sucked them off my feet. I got the message: pilgrimage abhors self-protection. When you walk on holy ground, no shoes!

Psalm 40:2-3

I was the only pilgrim on the sands in the early morning. The blessed solitude sanctified my final steps on St. Cuthbert’s Way. Halfway across, I began to hear an eerie keening sound, like wind through a broken wall. But that made no sense out on the tidal flat. After looking about with binoculars, I spied a dark mass at least a mile away. It was, I realized, hundreds of beached seals, pining for their absent sea.

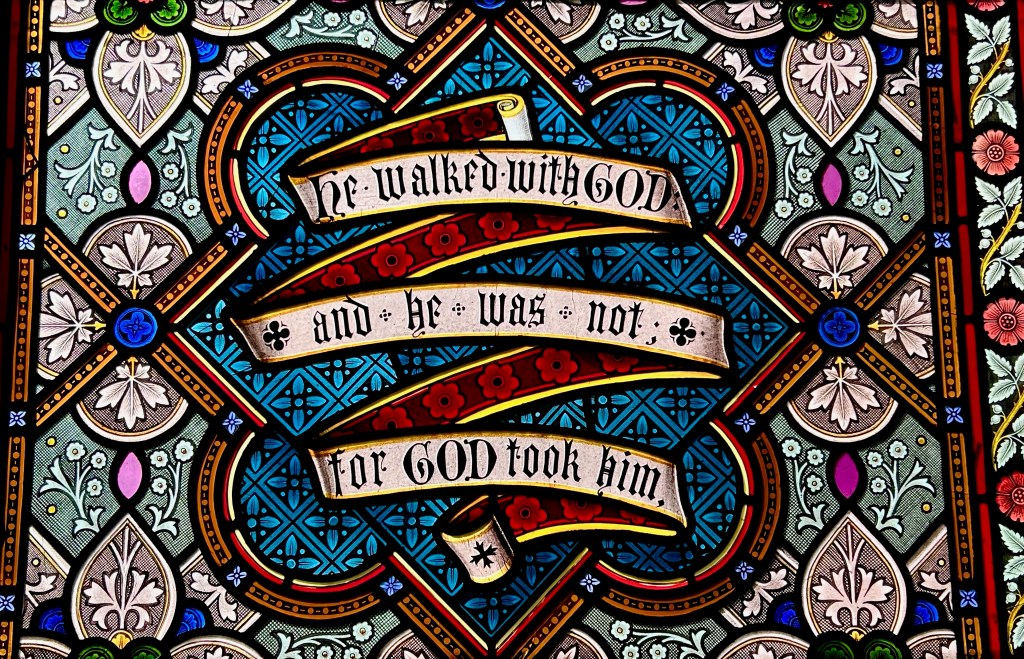

It took me seventy-five minutes to reach the other side, and another ten to find the parish church of St. Mary the Virgin, where I lit a candle to give thanks for the beautiful journey.

The Anglican parish church stands adjacent to the ruins of the twelfth-century Lindisfarne Priory, erected on the site of the seventh-century monastery founded by St. Aidan and nurtured by St. Cuthbert. I would return to this peaceful sanctuary again and again during my three-day sojourn on Holy Island. Sarah Hills, the gracious vicar, invited me to read Scripture at Morning and Evening Prayer. One of those passages was the comic narrative of Balaam and his recalcitrant speaking donkey, perhaps the oddest story in the Bible (Numbers 22:1-39). It was a very long text, so I tried to give each character a distinctive quality to sustain interest. The donkey’s voice got a few laughs.

On Ascension Sunday, the eucharist was crowded with pilgrims from many lands. I passed the Peace with Africans, Asians, Europeans, North and South Americans. The singing was spirited—no half-hearted voices after such a journey. Our harmonious sound enveloped me in the embrace of communal faith, and for a blessed hour my “I” became “we.” The offertory hymn happened to be “Lord of all hopefulness,” which celebrates the daily round of prayerful living: Be there at our waking … be there at our labors … be there at our homing … be there at our sleeping. I memorized it long ago in my teens, and I had sung it at the start of every day along Cuthbert’s Way. To repeat it now at Lindisfarne, with all the company of heaven, wasn’t just coincidence; it was grace. I received its gift with tears.

“They confessed their sins, confided in him about their temptations, and laid open to him the common troubles of humanity they were laboring under … Spirits that were chilled with sadness he could warm back to hope again … Those beset with worry he brought back to thoughts of the joys of heaven .…” [iv]

— The Venerable Bede, Life of St. Cuthbert

Cuthbert has, through the ages, been the most beloved of Britain’s northern saints. Although he left no writings of his own, his biographers describe a humble and prayerful man, full of charm, a citizen of heaven who devoted his life to the needs of earthly folk. He had a compassionate spirit, and was a gifted listener. When the responsibilities of leadership were thrust upon him, he accepted them in a spirit of obedience. But he had a hermit’s heart, and no thirst for power.

At age thirty, he became Prior of Lindisfarne in 664, and was assigned the difficult task of introducing the forms and practices of the Roman church to his resistant Celtic community. In a momentous decision at the recent Synod of Whitby, the Celtic churches in Britain had agreed to adopt the more universal—and hierarchical—norms of western Catholicism, surrendering the eccentricities of their more local traditions. But religious practices are hard to change, and Christian changemakers in every age have heard the same complaint, “But that isn’t the way we’ve always done it!” The seventh-century monks of Lindisfarne were no different than the Christians of our own time who fought women’s ordination or new forms of worship. They were uncomfortable. And they raised a fuss.

In Lindisfarne’s case, Cuthbert’s patient sweetness won the day. As the Venerable Bede tells the story,

“When he was wearied by the sharp contentions of his opponents he would rise up suddenly and with placid appearance and demeanor he would depart, thus dissolving the Chapter, but nevertheless on the following day, as if he had suffered no opposition the day before, he would give the same exhortations again to the same company until he gradually converted them to his own views.” [v]

The domestic complex was constructed later using greyer stones.

Time has erased the physical traces of Cuthbert’s Lindisfarne, but the impressive ruins of the Priory’s later structures still bear witness to his indelible legacy. After his death, pilgrims flocked to his shrine, thought to have been somewhere within the perimeter of the church built 500 years later. This video takes us through the ruins to the most likely spot.

The black stone marks the possible site of Cuthbert’s first burial.

After twelve years as prior here, Cuthbert felt an increasingly insistent call to solitude. For a time, he moved just offshore to a tiny island to seek the “green martyrdom” mentioned in the seventh-century Irish text, the Cambrai Homily:

Precious in the eyes of God:

The white martyrdom of exile

The green martyrdom of the hermit

The red martyrdom of sacrifice.[vi]

In other words, there are different ways to take up your cross. If your faith doesn’t literally kill you or drive you into exile, you can still withdraw from the world to wage without distraction the interior struggle for authenticity, what St. Benedict called the “single-handed combat of the wilderness.” Inspired by the desert hermits of Late Antiquity, many British ascetics took flight to wild and lonely places in the early Middle Ages.

You can walk to it at low tide.

It wasn’t long before Cuthbert moved further away, to the island of Inner Farne, a seven mile row from Lindisfarne. Its rocky terrain had sparse vegetation, but was teeming with birdlife: puffins, guillemots, terns, kittiwakes, eider ducks, and numerous other species. Cuthbert loved the natural world, and there are many charming stories of his interactions with birds and animals. Here is my favorite, told by Michael York in a video I made years ago about early British Christianity:

From The Story of Anglicanism: Early and Medieval Foundations

Cathedral Films, 1988

What was life like for an island hermit? Was it an escape from interdependence, or could it be a way of going deeper and deeper into the world? A twelfth-century Irish poem conveys a vivid sense of belonging to a sacred ecology:

Delightful I think it to be in the bosom of an isle, on the peak of a rock,

that I might often see there the calm of the sea.That I might see its heavy waves over the glittering ocean,

as they chant a melody to their Father on their eternal course.That I might see its splendid flocks of birds over the full-watered ocean;

that I might see its mighty whales, greatest of wonders…That contrition of heart should come upon me as I watch it;

that I might bewail my many sins, difficult to declare.That I might bless the Lord who has power over all,

Heaven with its pure host of angels, earth, ebb, flood-tide.That I might pore on one of my books, good for my soul;

a while kneeling for beloved Heaven, a while at psalms.A while gathering seaweed from the rock, a while fishing,

a while giving food to the poor, a while in my cell.A while meditating on the Kingdom of Heaven, holy is the redemption!

a while at labor not too heavy; it would be delightful! [vii]

Despite his affection for the created world, Cuthbert constructed his stone cell on Farne with high walls and no windows. His only view was through an opening in the roof. The design was intended to focus his attention on the higher things of “heaven,” not just as a concept, but as a physical, sensory experience. That strikes me as similar to what contemporary Light and Space artist James Turrell achieves with his “Skyspaces,” windowless rooms with a rectangular or elliptical opening cut into the ceiling.

“My art deals with light itself,” Turrell says. “It’s not the bearer of revelation—it is the revelation.” [viii] Instead of looking at material objects, you gaze up though the opening, taking in the sky’s color and light during the day and the stars at night. Over time this perceptual asceticism, screening out the world of things, quiets and deepens the eye, making it more receptive to the immaterial, more open to the infinite. Could the same thing have happened to Cuthbert in his stone enclosure? “It’s not about earth. It’s not about sky. It’s about our part in the luminous fabric of the universe.” [ix]

We can only speculate about the experiential nature of Cuthbert’s solitude, but Frederick Buechner, imagining the thoughts of another Northumbrian hermit, gives an honest appraisal of its challenges:

What’s prayer? It’s shooting shafts into the dark. What mark they strike, if any, who’s to say? It’s reaching for a hand you cannot touch. The silence is so fathomless that prayers like plummets vanish in the sea. You beg. You whimper. You load God down with empty praise. You tell him sins that he already knows full well. You seek to change his changeless will. Yet Godric prays the way he breathes, for else his heart would wither in his breast. Prayer is the wind that fills his sail. Else waves would dash him on the rocks, or he would drift with witless tides. And sometimes, by God’s grace, a prayer is heard.[x]

One of Cuthbert’s early hagiographers described the saint’s inner life as being free of struggle, anxiety or doubt. We are assured that “in all conditions he bore himself with unshaken balance.” [xi] But balance is hardly a prime directive for pilgrims of the Absolute. We may assume that Cuthbert knew his share of demons and dark nights on Farne. Nevertheless, the continuing stream of seekers to his island retreat found no solipsist lost in dreams or madness, but a compassionate listener who still had the gifts of a pastor. He always sent them away with lighter hearts than when they came.

Cuthbert spent nine years as a hermit, but in 685 the King of Northumbria and the Archbishop of Canterbury, hoping that this renowned holy man could help heal the divisive rivalries in the English Church, elected him to be the bishop of Hexham. The thought of leaving his “hiding place” on Farne made him sad, but when a distinguished delegation visited his hermitage to seek his consent, he yielded to the call. At least he managed to swap dioceses with another bishop, granting him oversight of his own beloved Lindisfarne. Whatever he lost in returning to the active life, it was not his soul. His anonymous biographer assures us that “he maintained the dignity of a bishop without abandoning the ideal of a monk.” [xii]

Two years later his health began to fail. At 51, he knew his days were numbered. He resigned his episcopate just after Christmas 686, then returned to his hermitage to die amidst the sound of seabirds, seals and crashing waves. He departed this life two weeks before Easter 687. The monks keeping vigil at his deathbed lit torches to signal his brothers at Lindisfarne that he had fallen asleep in Christ. His body was returned to the Priory for burial.

I wasn’t able to visit Inner Farne. Landings were suspended by an outbreak of Avian Flu. But the peace of Holy Island itself was blessing enough. Once the daytrippers flee back to the mainland before the tide returns, a profound calm settles in. It seemed almost deserted during the afternoons. In my days there, I sank into the solitude of grassy dunes, rambled through fields of spring color, enjoyed the tuneful chants of countless birds. Perhaps there was more Wordsworth than Cuthbert in the pleasure I took here—I suffered no rigorous austerities—but I hope that my bodily appreciation of Holy Island did honor to the saint’s own love for this place.

Holy Island is a busy hub for migratory flights between Britain, Scandinavia, southern Europe, even the Arctic and Africa. Some 337 different avian species have been identified here. The following audio was recorded around the site of Lindisfarne Priory in the early evening. If you want to spend two and a half minutes on Holy Island, close your eyes and listen.

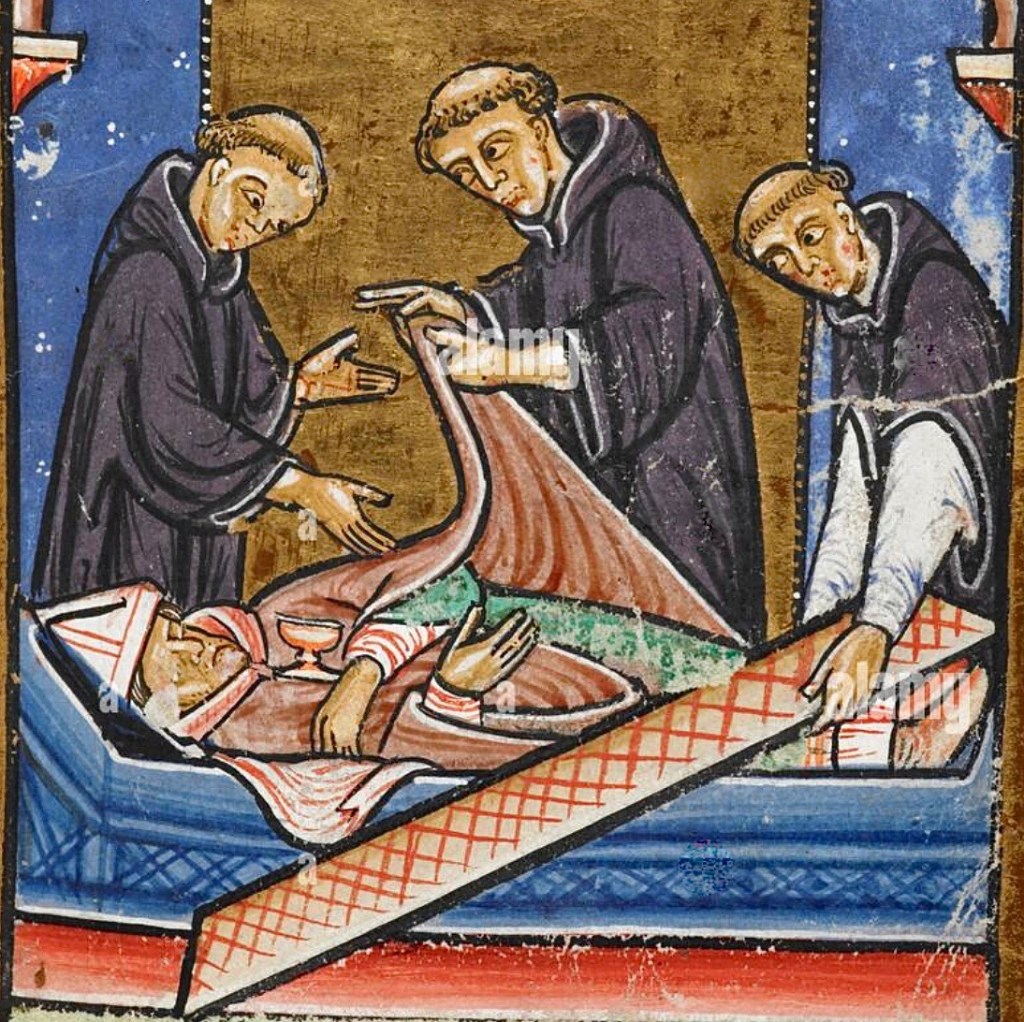

According to medieval custom, the remains of saints would be exhumed ten to twenty years after their death, so that their bones could be washed, wrapped reverently in silk or linen, and placed in a shrine for veneration.

But when the monks of Lindisfarne opened Cuthbert’s coffin in 698, they found his body “uncorrupted” and still intact. When news of this wonder spread, the stream of pilgrims grew to a flood. Sadly, Cuthbert’s body would not rest in peace here for long. Not on a defenseless coastline in the age of the Vikings.

In 793, the peace of Lindisfarne was shattered when Viking marauders sacked the Priory. Remarkably, Cuthbert’s shrine survived the damage. Eighty years later, there was a second raid. It was even worse.

“And they came to the church of Lindisfarne and laid everything waste with grievous plundering, trampled the Holy Places with polluted feet, dug up the altars and seized all the treasures of the Holy Church. They killed some of the brothers, they took some of them away in fetters, many they drove out naked and loaded with insults and some they drowned in the sea …” [xiii]

It was the end of an era for Lindisfarne, but Cuthbert’s own story had one more chapter. Just before the second Viking invasion, the saint made his getaway from Holy Island when a small band of brothers lifted his wooden coffin from the Priory shrine and carried it across the tidal flats to the mainland. Thus began two centuries of wandering in exile for Cuthbert’s remains, until he finally came to rest in the newly built cathedral at Durham in 1104.

Monks carry Cuthbert’s coffin away from Holy Island to protect it from Viking raiders.

On my third morning at Holy Island, I rose early to cross back over the sands. My own wandering was not yet done. I would follow the saint to Durham.

The path I walk, Christ walks it.

May the land in which I am be without sorrow.

May the Trinity protect me wherever I stay…

May bright angels walk with me — dear presence — in every dealing…

May every path before me be smooth.

Well does the fair Lord show us a course, a path. [xiv]

THE ST. CUTHBERT SERIES CONCLUDES:

The Journey Ends: Durham Cathedral

Photographs, videos and nature recordings are by the author.

“For All the Saints” is sung by the choir and congregation of St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, Bainbridge Island, Washington, with Paul Roy on organ.

The first installment of this pilgrimage account, Walking St. Cuthbert’s Way, may be found at https://jimfriedrich.com/2023/07/28/walking-st-cuthberts-way/

For more on James Turrell: https://jimfriedrich.com/2015/08/06/the-woven-light-reflections-on-the-transfiguration/

[i] The line is from Derek Walcott’s poem, “Love After Love.”

[ii] Buechner’s fine novel is about a 12th century hermit saint in the north of England. It made excellent reading on St. Cuthbert’s Way.

[iii] #128 in The Sacred Harp, with lyrics by Samuel Stennet (1787).

[iv] Bede, Life of St. Cuthbert, 22, quoted in Mary Low, St. Cuthbert’s Way: A Pilgrim’s Companion (Glasgow: Wild Goose Publications, 2019). The great historian of early English Christianity is a key source for Cuthbert’s life. Born 14 years before the saint’s death, he was able to interview some who had known Cuthbert in life when he wrote his biography.

[v] Bede’s Life of Cuthbert, quoted in Philip Nixon, St. Cuthbert of Durham (Gloucestershire: Amberly Publishing, 2012), 33.

[vi] Isabel Colgate, A Pelican in the Wilderness: Hermits, Solitaries and Recluses (New York: Counterpoint, 2002), 104. The Cambrai Homily (7th or 8th century) is the earliest known Irish homily. The “green” martyrdom refers to rigorous ascetic practice not requiring either a pilgrimage journey or a complete disconnection from the world. The Irish word glas may be translated as blue as well as green, perhaps referring to turning blue after praying the Psalter all night in a cold river, or developing a sickly complexion from too much austerity.

[vii] In a Penguin anthology of Celtic writings I had years ago.

[viii] James Turrell, quoted in Jan Butterfield, The Art of Light and Space (New York: Abbeville Press, 1993), 73.

[ix] E. C. Krupp, writing about Turrell in James Turrell: A Retrospective (Los Angeles: County Museum of Art, 2013), 246.

[x] Frederick Buechner, Godric (New York: Harper One, 1980), 142.

[xi] Anonymous Life of Cuthbert, 3.7, quoted in Low, 47.

[xii] Anonymous Life, quoted in Nixon, 47.

[xiii] Simeon of Durham (d. circa 1129) was an English chronicler and monk at Durham Priory. Quoted in Nixon, 59.

[xiv] Ireland, 6th century.