In all four gospels, there’s a story about a woman who interrupts an intimate dinner party to kneel at the feet of Jesus and make an act of devotion. Luke’s story differs from the others in significant ways, so it may be based on a different incident. But Mark, Matthew and John all seem to be describing the same event. It was a moment which clearly had an indelible impact on the memory of the early Church.

John’s version is the only one which names the woman: Mary of Bethany, whose brother Jesus had just raised from the dead in the gospel’s previous chapter. Coming between the dramatic raising of Lazarus from the tomb and the violent clamor of the Passion, the story is a striking contrast to what came before and what comes after.

Instead of a public event with lots of people, it is quiet and intimate. No wailing mourners, no crowd shouting “Hosanna!” or “Crucify him!” Just Jesus, a few disciples, and his hosts, the siblings of Bethany: Martha, Mary, and Lazarus.

We don’t know what they talked about during that dinner, but the moment had to have been highly charged, given the people around the table: The sisters whose grief had driven the harsh confrontation with Jesus at their brother’s tomb (If you had been here, my brother would not have died!) … the rabbi from Nazareth who had wept his own tears over the death of his friend (and perhaps some tears for the human condition in general) but who also found himself channeling the awesome life-giving power of the divine through his own mortal body …and the stunned man who had been so suddenly snatched from the land of the dead, experiencing what had to be a volatile mixture of awe, gratitude, and PTSD.

Perhaps no one said very much at all. Perhaps they were all still processing the shock of their shared experience at the tomb, letting a profound silence hold their feelings in order to preserve the mystery of it from being reduced to the poverty of language. But at some point, Mary was inspired to acknowledge the sacredness of the moment—not with words, but with a sacramental action.

The text doesn’t give the details, but I imagine her rising from the table, leaving the room for a moment, then returning with a jar of nard, a fragrant oil originating in the Himalayas and transported at great expense along the ancient trade route from Asia to the Middle East. It was worth a year’s wages, so when Mary, without saying a word of explanation, poured it all out over the feet of Jesus, it was quite shocking, like throwing a bag of gold into the sea or setting fire to a pile of paper money.

Then Mary compounded the shock by letting down her hair and using it to rub the oil into Jesus’ skin. No reputable woman would have done such a thing, nor would a religious teacher have permitted himself to be touched in such a way. Nevertheless, that’s how it went.

Judas was at that table, and he couldn’t bear to watch. He was the apostles’ money man, and he objected to wasting wealth that could have done some real good. John’s gospel doubts his sincerity, accusing Judas of embezzling the very funds he was claiming to protect.

I suspect that Judas’ discomfort had more to do with Jesus rewriting the social codes of his culture by endorsing Mary’s action. “Leave her alone,” Jesus tells him. Jesus, unlike Judas, understood that this was a very precious and significant moment, and he wanted to let it happen.

Mary’s extraordinary action, both sensual and symbolic, overflowed with meanings. For one thing, anointing with oil was a way to mark the special vocation and identity of authoritative figures, whether powerful rulers or holy persons. It consecrated them as chosen and set apart. The title of “Messiah” or “Christ” means “the anointed one.”

It was revolutionary to have a woman be the one to anoint Jesus as priest and ruler, but the kingdom of God was all about revolution: the revolution of transforming a disordered and broken world into a more perfect expression of divine intention and human possibility.

Anointing was also part of the culture’s preparation of a body for burial. Performed in the week before Jesus’ death, Mary’s gesture inaugurates the sequence of sacrificial acts culminating with her Lord’s burial in the stone-cold tomb. The feet she anoints will soon walk the Way of the Cross for the salvation of the world. That was Jesus’ chosen destiny, and the oil is an outward and visible sign of his inward consent to perform that destiny.

The story’s third meaning is in its foreshadowing of the foot-washing, when Jesus, on the night before he died, knelt at the feet of his friends to perform the work of a servant, surrendering his power for love’s sake. The foot-washing marked the turning point from a paradigm of domination to a paradigm of communion.

By kneeling at the feet of his friends, Jesus was showing them, and us, an image of humanity’s best version of itself. In that sacramental act, Jesus was saying: This is how we must be with one another, because this is exactly how God is with us.

And in today’s story, just a few days before Jesus would teach this explicit lesson at the Last Supper, Mary of Bethany, foreshadows the foot-washing when she offers, in her own way, all she has, holding nothing back.

And her devotional act of kneeling down to pour out the precious oil not only anticipated the foot washing on Maundy Thursday, it was an image of the divine nature as revealed in the incarnation and crucifixion of Jesus. As one theologian has put it, “The self-giving extravagance of Mary’s actions point to the way Jesus would expend himself completely through his crucifixion.” [i]

In our Palm Sunday liturgy next Sunday, Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians will declare that Jesus emptied himself for us, poured himself out for us, and in so doing he revealed who God is and what God does. Whether in the costly pouring out of the Son’s life on the cross, or in the lavish pouring out of Spirit on Pentecost, God is the One who never ceases to pour out God’s own self.

And when, before his own self-offering, Jesus allowed Mary to anoint him in such a costly manner, she herself became an icon who shows us God with her own body, bowing before Jesus to wipe his feet so tenderly with her hair.

At the time, the disciples did not grasp the full significance of Mary’s act. Nor did Mary herself, I’d imagine. How could they?

As we say around here about Holy Week: The journey is how we know. The disciples had to learn by doing: following Jesus all the way to the cross—and beyond—before they could begin to understand—through memory and reflection—what it was all about. And that is what we will be doing as well during the seven days of Holy Week, not wanting to miss a single step along that sacred way. The journey is how we know.

Before we leave this story, consider the one sentence that stands out from the rest of the text:

The house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume.

There’s nothing else quite like it in the canonical gospels. The Bible in general is short on description and long on action. We never hear about the weather in Jerusalem or the colors of spring in the Galilean hills or the way light falls on the walls of the temple courtyard in late afternoon. So why does John invite us to pause and take in the sweet smell of nard?

In her fascinating book on the olfactory imagination in the ancient Mediterranean, Susan Ashbrook Harvey points out that aromatic spices were thought of as souvenirs of Paradise. When Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden, it was said, they were allowed to take away a few fragrant plants to remind them of what they had lost.

Smells are a powerful trigger of memory, and the sweet odors of plants, spices and aromatic oils not only reminded people of Paradise Lost, they were thought to alert our senses to divine presence in a fallen world. They help us remember God. As Harvey writes, fragrance is something like God:

“Unseen yet perceived, smells traveled and permeated the consciousness, transgressing whatever boundaries might be set to restrict their course … Odors could transgress the chasm that separated the fallen order from God; they could elicit an unworldly sensation of beauty.” [ii]

And so we hear St. Paul speak of the fragrance that comes from being “in Christ,” so that we ourselves begin to give off the “aroma of Christ” from our own bodies (2 Corinthians 2:14-16). A few centuries later, Gregory of Nazianzus, in his treatise on the effects of our baptism, wrote:

“Let us be healed also in smell, that we … may smell the Ointment that was poured out for us, spiritually receiving it; and [that we may be] so formed and transformed by it, that from us too a sweet odor may be smelled.” [iii]

And St. Chrysostom, in his 5th-century sermon on today’s gospel, urged his congregation to become like thuribles, sweetening wherever they happen to be with the incense of heaven:

Now the one who perceives the fragrance knows that there is ointment lying somewhere; but of what nature it is he does not yet know, unless he happens to have seen it. So also we. [That God is, we know, but what in substance we know not yet.] We are then, as it were, a royal censer, breathing whithersoever we go of the heavenly ointment and spiritual sweet fragrance.” [iv]

In the spirit of such olfactory tropes, John’s verse about the sweet smell of the nard in that Bethany dining room endow that moment with divine peace and blessing. And the verse is especially vivid in contrast with the stench of mortality hovering around the tomb of Lazarus a few days earlier. Don’t roll away the stone, his sister pleaded. After 4 days inside, the body will smell terrible. Or as the King James Bible memorably put it, “by this time he stinketh.”

But in that sweet-smelling dining room with Jesus and his friends, death and decay are held at bay for a few precious hours. Outside, the world is wild and raging, on the verge of murdering the incarnation of Love. But inside, a woman is imaging the peace of heaven at the feet of her Lord.

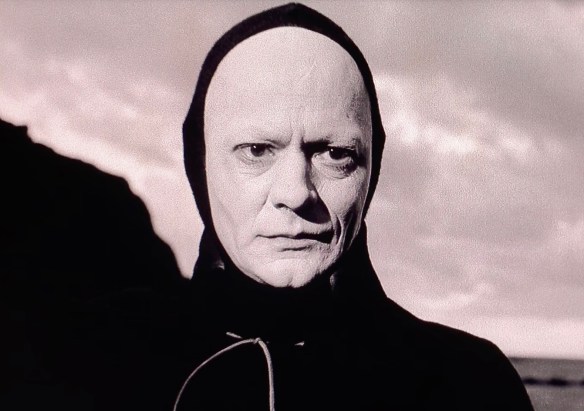

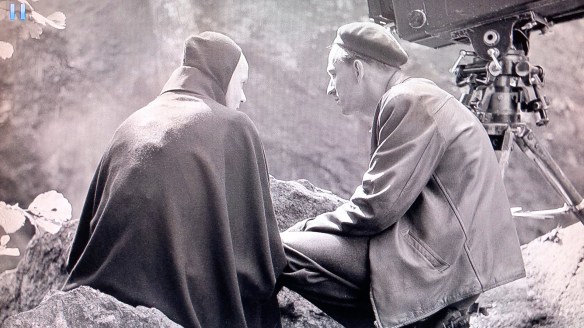

For me, this beautiful moment calls to mind a scene from Ingmar Bergman’s classic 1957 film, The Seventh Seal, set in the fourteenth century when the Black Plague is ravaging Europe. A wandering knight is trying to get back home before the plague catches him, stalling for time by engaging Death in a game of chess. He’ll never win, of course, but at one point he meets a kind of holy family: a man, Jof; his wife Mia; and their baby, Michael. They are traveling players who embody the vitality of the life force.

The film ends with the knight taking his inevitable place in the dance of Death, disappearing over the horizon with his fellow mortals. But the “holy family” are not seen among the dead souls, for they have been spared to carry on in this life, untroubled by death because they belong to grace. They know how to accept the music of what happens, and not live in fear.

In the sweetest moment of this anguished film, Jof and Mia share their strawberries and milk with the knight, who receives it like a sacrament, a taste of unconquerable life:

“I shall remember this hour of peace,” he tells them. “The strawberries, the bowl of milk, your faces in the dusk, Michael asleep, Jof with his lute. I shall remember our words, and shall bear this memory between my hands as carefully as a bowl of fresh milk. And this will be a sign and a great content.”

An hour of peace, an experience of great content in a world that is coming apart—isn’t that a perfect description of the dinner at Bethany? And are we not in that same place now, with Mary, Jesus, and the rest? The powers of death and malice and mindless destruction are raging outside. We know that. Yet here we are, tasting the bread of heaven, inhaling the fragrance of divine presence.

It’s not about escaping. Not at all. It’s about renewal, so that when we go back out into the world, we can be clear about our vocation: to exude that fragrance—God’s sweetness—in every place we go. And when it gets hard out there—and it will—just call to mind the fragrance of those sacred moments when we dwell in God, and God in us.

This homily was preached at St. Barnabas Episcopal Church on Bainbridge Island in Washington State, on the Fifth Sunday in Lent.

[i] Craig R. Koester, Symbolism in the Fourth Gospel: Meaning, Mystery, Community (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995), 114.

[ii] Susan Ashbrook Harvey, Scenting Salvation: Ancient Christianity and the Olfactory Imagination (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006), 53.

[iii] Ibid., 75.

[iv] Ibid., 115.