Sermon for Trinity Sunday 2024 at St. Barnabas Episcopal Church, Bainbridge Island, Washington

From late autumn to late spring, Christian liturgy takes us on a ritual journey through the gospel narrative, from the Incarnation and Epiphany of Christ to the dramatic finale of Passion, Resurrection, Ascension and Pentecost.This great sequence concludes with Trinity Sunday, which serves as a kind of epilogue.

The abrupt shift from the engaging world of story to the tangled thicket of doctrine can be a bit of a shock. It’s like going directly from a seminar in English literature to a class in advanced calculus. Our hearts sink and our heads explode. But fear not. The Trinity is no dreary abstraction. Nor is it a matter, as Lewis Carroll might say, of believing three impossible things before breakfast. We are not here to solve once and for all the puzzle of Three-in-One and One-in-Three. We are here to adore the mystery.

The first Christians were not inventive theorists speculating about the divine nature of a generic God. They were the friends of Jesus trying to make sense of the concrete, experiential data of salvation, beginning with the dramatic biblical events they had lived through and continuing to unfold in the common life of their believing communities. Their profound experiences of Jesus and the Holy Spirit had shaken the foundations of their monotheistic faith, and they were trying to sort out the implications.

Jesus and the Spirit had done for them what only God can do: heal, save, sanctify—even vanquish the power of death. Did that make Jesus and Spirit divine? And if so, what did that multiplication of divine persons do to their belief that God was one? Jesus had told them, “I and the Father are one.” But it would take centuries to agree on what he meant.

Without losing the unity of God, how could the early Christian community account for the divine diversity revealed in the saving activities of Christ and the Spirit?

Once they began to call Jesus Kyrios (Lord), which happened very early in their worship and their storytelling, traditional monotheism was radically destabilized. The growing perception of the Holy Spirit as a guiding and empowering presence of deity in their communities only compounded the problem.

There were various attempts to solve the issue by downgrading Jesus and Spirit to subordinate, derivative, or semi-divine realities, by no means equal to the eternal and uncreated God. Such “heresies” were popular with those who wanted to keep God simple. But “orthodoxy” was unwilling to deny the fullness of divinity to either Christ or the Spirit. For them the bottom line was this:

Only God can save us. Christ and Spirit, in the biblical revelation and Christian experience, are integral and essential to salvation. Therefore, they must be “of one substance with the Father.” That is to say, the Persons are all equally integral to the divine reality: God above us, the source and ground of all being; God with us and among us, the companion who is our way, our truth, and our life; and God within us, the energy and vitality of our deepest self. As the theologians put it:

“The Trinity is an account of God that says these are [each] irreducible and indispensable dimensions of the same reality, not different ones, and yet each has its own irreducible integrity.” [i]

And so, a trinitarian faith became foundational for the Christian understanding of divinity: God in three persons, blessed Trinity. But the inherent tension between the one and the three remains to this day. Human thought and human language can’t quite manage to think both things at the same time. It’s like waves and particles. Gregory of Nazianzus, one of most influential shapers of the fourth-century trinitarian consensus, admitted the futility of trying to corral the mystery with concepts. He suggested that we just go with the divine flow:

“I cannot think of the One without immediately being surrounded by the radiance of the Three; nor can I discern the Three without at once being carried back into the One.” [ii]

In an amusing caricature of crudely literal images of the Three-in-One, British theologian Keith Ward imagines three omniscient individuals trying to have a conversation:

“I think I’ll create a universe,” says one. “I knew you were going to say that,” says the second. “I think I’ll create one as well,” says the third. “Well, it had better be the same as mine,” says number one. “You already know that it is,” says number two. “I knew you were going to say that,” says number three.[iii]

If we have difficulty with “God in three Persons,” it is because we think of a person as defined by his or her separateness. I’m me and you’re you! We may interact and even form deep connections, but my identity does not depend upon you. I am a self-contained unit. You can’t live in my skin and I can’t live in yours. That’s the cultural assumption, which goes back at least as far as Descartes in the seventeenth century and continues today in such debased forms as rampant consumerism and economic selfishness, where my needs and my desires take precedence over any wider sense of interdependence, community, or ecology.

But what we say about the Persons of the Trinity is quite different. Each Person is not an individual, separate subject who perceives the other Persons as objects. The Trinitarian persons experience one another not from the outside, but from the inside. They indwell each other in a mutual interiority.

But if the divine Persons are all inside each other, commingled, “of one being,” as the Creed says, what makes each Person distinct? To put it succinctly: the Persons are distinct because they are in relation with one another. No Father unless there is a Son. No Son without a Father. No Holy Spirit without Father and Son.

As Martin Buber observed, we are persons because we can say “Thou” to someone else. To be a person is to experience the difference – and the connection – that forms the space between two separate subjects. My consciousness is not alone in the universe. There are other centers of consciousness: Thou, I… Thou, I… The fact that you are not I is what creates self-consciousness, the awareness of my own difference from what is outside myself.

If we apply this to the Trinity, we say that there are Three Persons because there is relation within God, relation between the Source who begets, the Word who is begotten, and the Spirit who binds the two together and moves them outward in ever widening circles.

These relations are not occasional or accidental. They are eternal. There is an eternal sending within God, an eternal self-giving within God, an eternal exchange by which God is both Giver and Receiver simultaneously. God is Love giving itself away – self-emptying, self-diffusing, self-surrendering – and in so doing finds itself, receives itself, becomes itself. A French mystic put it this way: “it’s a case of un ‘je’ sans moi” (an “I” without a me).

Wallace Stevens wrote a poem about the process of giving ourselves over to a larger whole. He called it “the intensest rendezvous,” where we find ourselves drawn out of isolation “into one thing.” He wasn’t writing about the Trinity, but his words come as close as any to describing the essential dynamic of the divine Persons:

Here, now, we forget each other and ourselves.

We feel the obscurity of an order, a whole,

A knowledge, that which arranged the rendezvous.[iv]

As Orthodox theologian John D. Zizioulas says in his influential text, Being as Communion, “To be and to be in relation are the same thing for the divine life … Therefore if Trinity is our guide, the most fundamental definition of being we can give is person-in-communion … The being of the one divine nature is the communion of the irreducibly different persons; the being of the individual persons is constituted by their relations with each other.” [v]

God is not a simple, static substance but an event of relationships. That’s why we say that God is love. “To be” has no ontological reality apart from “to be in relationship.” In the words of Anglican priest John Mbiti of Kenya, expressing the strongly communal mindset of African theology, “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am.” [vi]

Each Person contains the others and is contained by them in a shared communion of self-offering and self-surrender. But that continuous self-offering is never a one-way transaction, either one of self-emptying or one of being filled. It is always both at once – giving and receiving – as we ourselves know from our own mutual experience of love at its best.

Trinitarian faith describes a God who is not solitary and alone, a God who is not an object which we can stand apart from and observe. The Trinity is an event of relationships: not three separate entities in isolation and independence from one another, but a union of subjects who are eternally interweaving and interpenetrating

This divine relationality is not something which an originally solitary God decided to take up at some point. God is eternally relational. Before there was an external creation to relate to, God’s own essential self was and is an event of perpetual relation. There was never simply being, but always being-with, being-for, being-in. To be and to be in relation are eternally identical.

When the Bible says, “God is love” (I John 4:16), it means that love is not just something God has or something God does; love is what God is.

As John Zizioulas puts it, “Love as God’s mode of existence … constitutes [divine] being.”[vii] Feminist theologian Elizabeth Johnson echoes this when she says, “being in communion constitutes God’s very essence.” [viii] In other words, God is Love giving itself away—self-emptying, self-diffusing, self-surrendering—and in so doing finds itself, receives itself, becomes itself. The theologians of late antiquity borrowed a word from the arts to describe this process: perichoresis, which means to “dance around.”

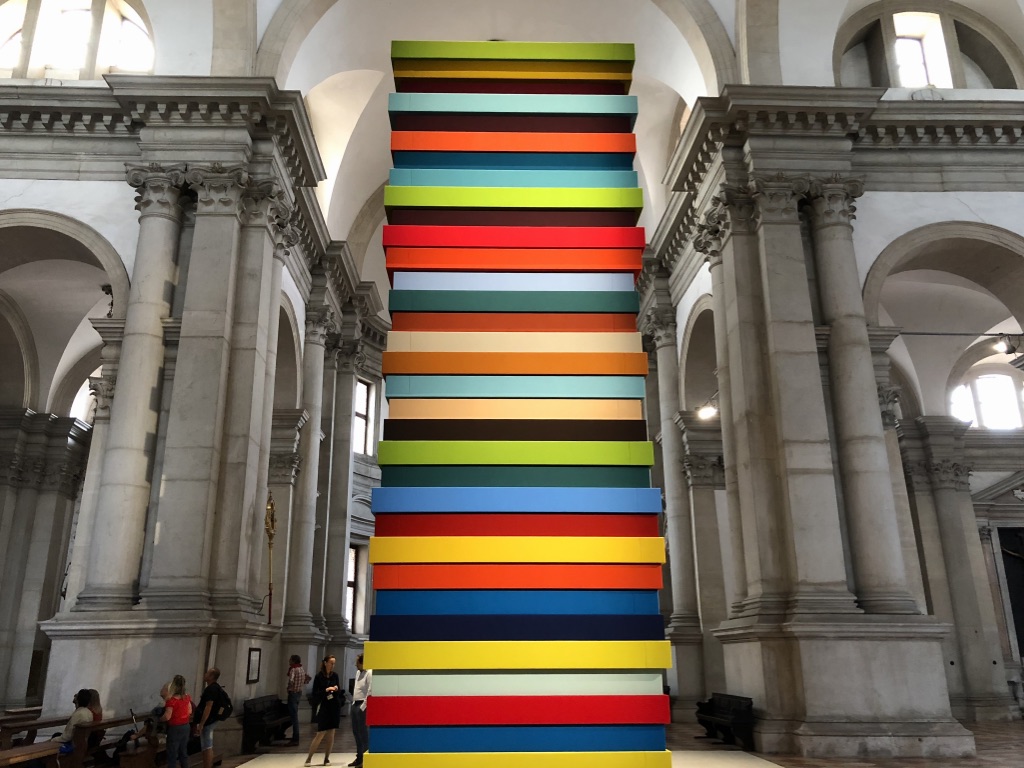

Trinity is a dance, with Creator, Christ and Spirit in a continuous movement of giving and receiving, initiating and responding, weaving and mingling, going out and coming in. And while our attention may focus at times on a particular dancer, we must never lose sight of the larger choreography to which each dancer belongs: the eternal perichoresis of Three in One, One in Three.

As Jesus said, “losing” yourself and “finding” yourself are equivalent and simultaneous. In giving ourselves away, we receive ourselves back. This may be counterintuitive to the modernist mindset of autonomous individual self-possession, but it is the essence of communion: “a giving of oneself that can only come from the ongoing and endless reception of the other.” [ix]

If we had the space, I would invite you now to dance the divine perichoresis with your own bodies. We would join hands, circle round, spiral inward, weave in and out of the arches and tunnels of upraised arms, and manifest with our bodies the divine fullness of the Holy Trinity, which has been described as an “interdependence of equally present but diverse energies … in a state of circumvolving multiplicity.” [x] And thus we would, both symbolically and in fact, participate in the divine reality of “reciprocal delight” [xi] which transpires not only in heaven, but “on earth as it is in heaven.”

There are no spectators in the Trinitarian dance, which is always extending outward to draw us and all creation into its motions. As Jürgen Moltmann said, “to know God means to participate in the fullness of the divine life.” [xii]

It’s not a matter of our trying to imitate the relational being of the loving, dancing God, as if we were inferior knock-offs of the real thing. God wants us to become ourselves the real thing. God wants to gather us into the divine perechoresis as full participants in the endless offering and receiving, pouring out and being filled, which is the dance of God and the life of heaven.

And while our dance with God has its mystical, mysterious, transcendent dimensions, it is also very concrete and specific to our historical life on this earth. The divine life of communion and self-diffusive love is the only antidote for the poisonous hatreds of this fearful age.

We know the yoke of sin and death,

Our necks have worn it smooth;

Go tell the world of weight and woe

That we are free to move. [xiii]

Because we ourselves are made in God’s image, who God is matters deeply, both for our own self-understanding and for our engagement with the world. The Trinity isn’t only God’s life. It is ours as well. It’s the shape of every story, the deep structure of the church, and the foundational pattern of reality.

Because God is communion, the eternal exchange of mutual giving and receiving, then God’s Church must live a life of communion as well. When Love’s perechoresis becomes our way of being in the world—as believers, as church—the Trinity is no longer just doctrine or idea. It is a practice, begetting justice, peace, joy, kindness, compassion, reconciliation, holiness, humility, wisdom, healing and countless other gifts. As theologian Miroslav Volf has said, “The Trinity is our social program.” [xiv]

The dance of Trinity is meant

For human flesh and bone;

When fear confines the dance in death,

God rolls away the stone. [xv]

The Church exists to participate in the liberating life of God, and to enable others to do the same. We exist to make divine communion not just an inner experience but a public truth. We don’t just feel God’s perichoresis. We don’t just feel Love’s eternal dance. We embody it. We live it. We show it. We share it.

As the great Anglican preacher Austen Farrer put it so clearly a century ago:

“It is not required of us to think the Trinity.

We can do better; we can live the Trinity.” [xvi]

Photographs by the author.

[i] S. Mark Helm, The Depth of the Riches: A Trinitarian Theology of Religious Ends (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 132.

[ii] Gregory of Nazianzus, q. in Karen Armstrong, The Case for God (New York: Knopf, 2009). 116-117.

[iii] Keith Ward, God: A Guide for the Perplexed (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2003), 235.

[iv] Wallace Stevens, “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour,” Collected Poetry and Prose (NY: Library of America, 1997), 444.

[v] John D. Zizioulas, Being as Communion: Studies in Personhood and the Church (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1993), 46.

[vi] quoted in Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen, The Trinity: Global Perspectives (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2007), 352.

[vii] Zizioulas, 46.

[viii] Elizabeth Johnson, She Who Is: The Mystery of God in Feminist Theological Discourse (NY: Crossroad, 1993), 227.

[ix] Graham Ward, “The Schizoid Christ,” in The Radical Orthodoxy Reader, ed. John Milbank and Simon Oliver (NY: Routledge, 2009), 241.

[x] David Bentley Hart, The Beauty of the Infinite: The Aesthetics of Christian Truth (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 2003), 114.

[xi] St. Athanasius (c. 296-373), a bishop in Roman Egypt, was a key defender of Trinitarianism.

[xii] Jürgen Moltmann, The Trinity and the Kingdom: The Doctrine of God, trans. Margaret Kohl (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1981), 152.

[xiii] Richard Leach, “Come Join the Dance of Trinity.”

[xiv] Miroslav Volf, “‘The Trinity is Our Social Program’: The Doctrine of the Trinity and the Shape of Social Engagement,” Modern Theology 14, no. 3 (July 1998).

[xv] Leach.

[xvi] Austin Farrer, The Essential Sermons (London: SPCK, 1991), 78.