What on earth happened last night—at that little stable on the edge of town? It was all so strange, so unbelievable. Some of us are still sleeping it off. Some of us didn’t get any sleep at all, or maybe we were asleep the whole time and it was all just a dream.

There was a really bright star, and then the sky started singing: Gloria in excelsis Deo! It was angels, someone said. I don’t know about that, but it was so beautiful, as if music were being invented for the very first time.

And suddenly, we all started running, don’t ask me why, until we came to this cave––it was a stable with a cow and a couple of donkeys––and in the back there was a woman lying down on some hay, and a man kneeling beside her. And between them there was a little baby, just a few hours old, I’d say. What a place to begin your life! They must have been pretty desperate to end up there. Maybe they were refugees. Or undocumented. I don’t know. But they didn’t look scared or out of place. They seemed to belong there. And you know, I had the feeling that I belonged there too. We all did.

I can’t really explain it, but I got this feeling that everything in my life before that had just been waiting around for this moment, as if after a long and pointless journey I had finally come home.

And I know it sounds weird, but I swear that little baby looked right at me, as if he knew who I was––or who I was going to be, because when I left that stable I knew––I knew!––that my life was never going to be the same. Pretty crazy, right? I kind of hope it was just a dream, because if it’s not—where is all this going to take me?

That’s how I imagine the morning after speech of a Bethlehem shepherd. Intoxicated by wonder, struggling to make sense of it, and feeling both curious and anxious about what happens now, after this wondrous birth. What happens to me, to you, to the whole wide world? A change is gonna come, yes it will. Yes it will, because what happens in Bethlehem doesn’t stay in Bethlehem. It goes home with us, it gets in our blood, it becomes part of our story. Nothing in the world will ever be the same again. Nothing in our lives will ever be the same again.

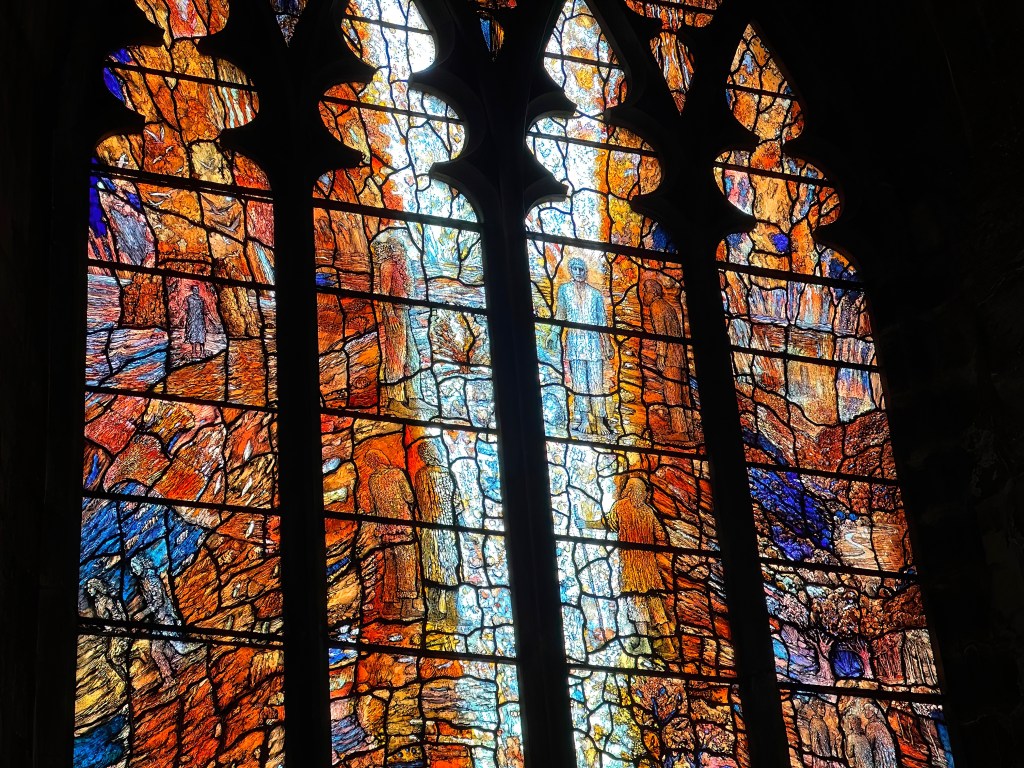

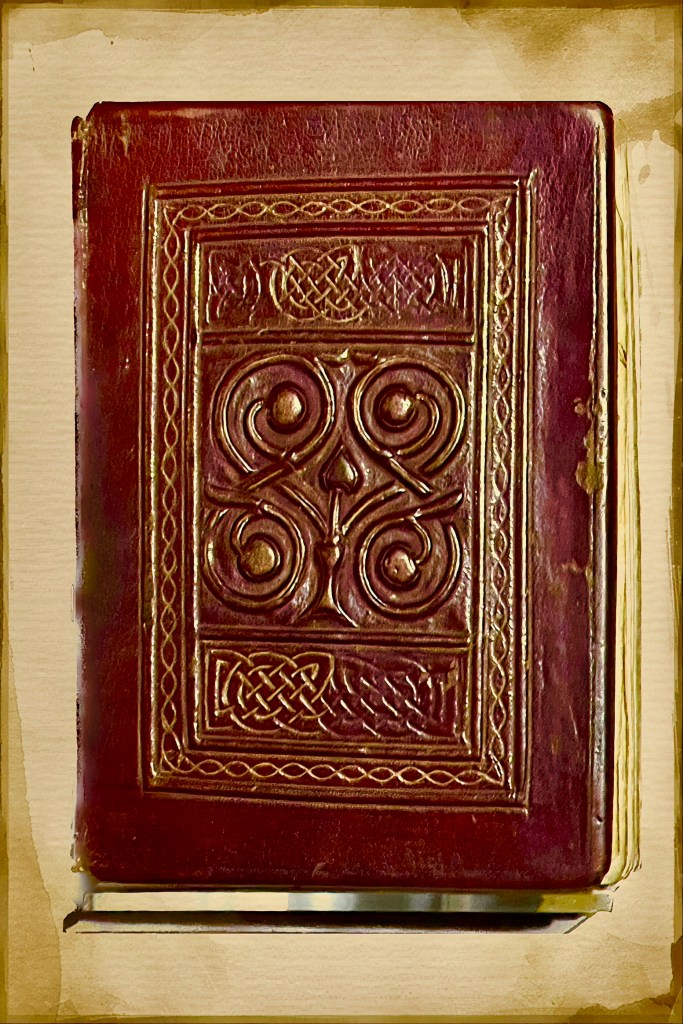

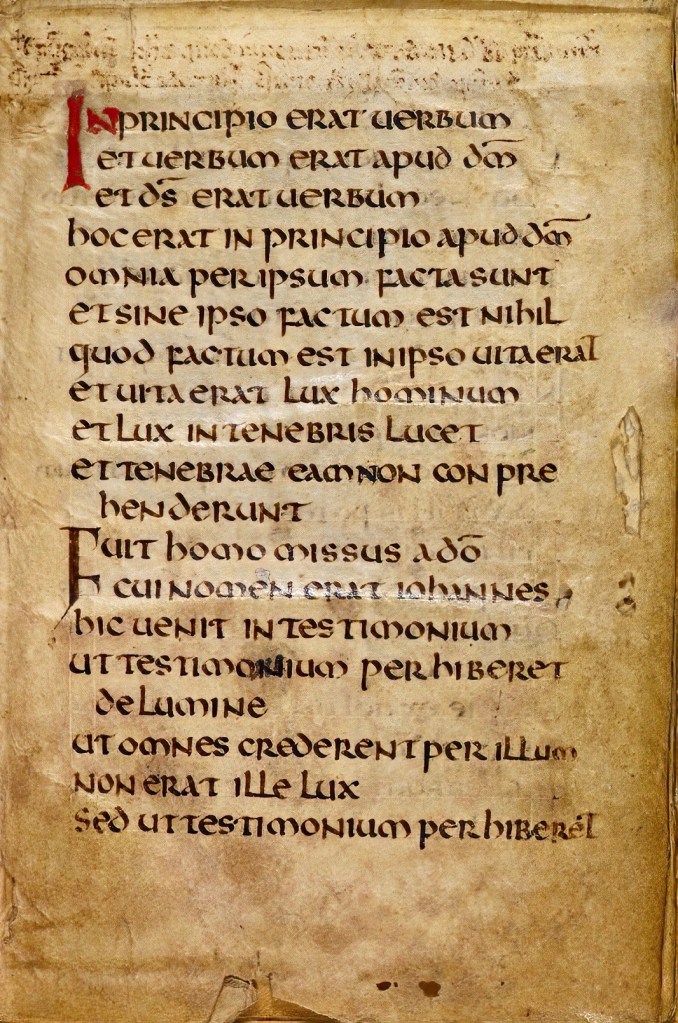

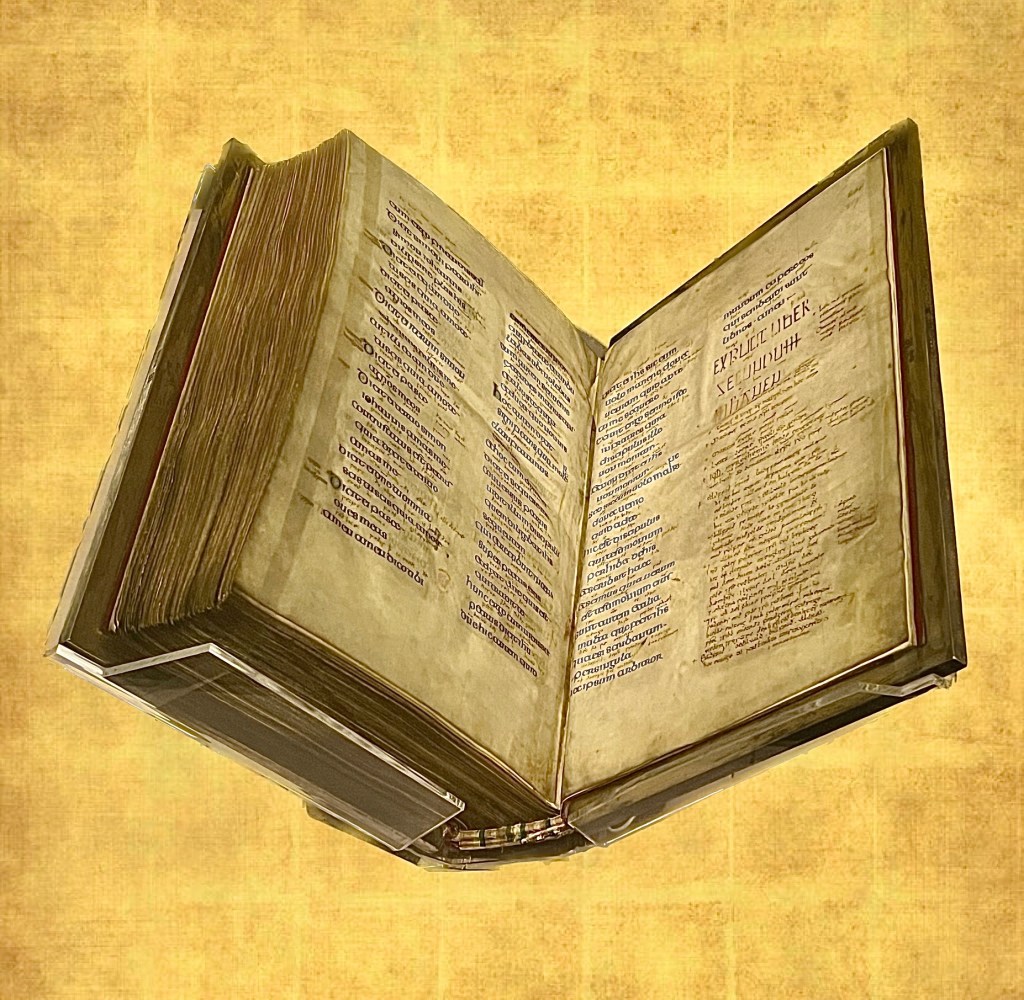

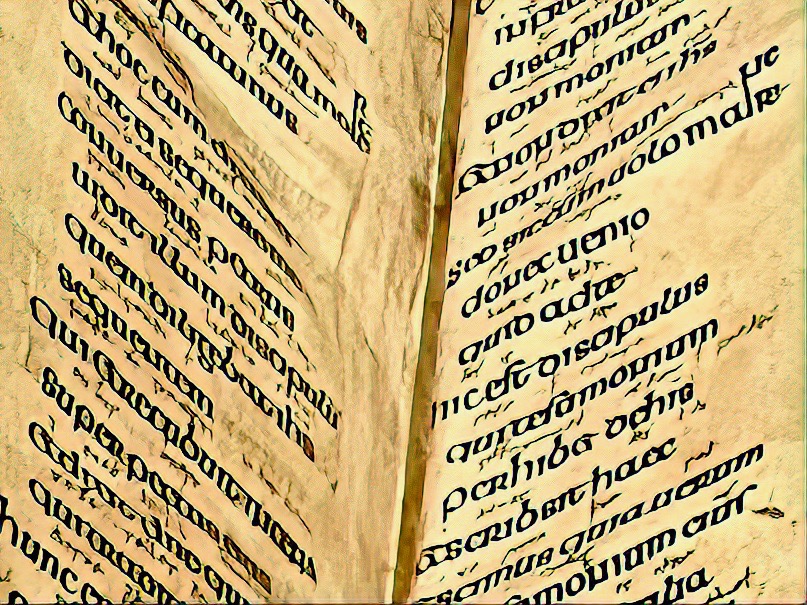

And that is why, on the morning after, we listen to St. John’s grand prologue to the Fourth Gospel. Its cosmic perspective on the birth of Christ reminds us how vast and consequential was that humble birth in a lowly stable.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being. . . And this divine Word became flesh and lived among us. (John 1:1-14)

In other words, God was not content to remain purely within the essence of the divine self. God desired to go beyond the inner life of the divine, to enter the confines and contingencies of time and space and history, to become incarnate as the mortal subject of a human life and experience the human condition from the inside. The Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.

What a fantastic thought: God wants to be with us—not just love us at a distance but to be intimate with us, in communion with us, participating in our humanity while enabling us to participate in divinity, because Incarnation means that divinity and humanity are now and forever inextricably joined. Joy to the world, the Lord is come … let every heart prepare him room.

But perhaps we have some doubts about our capacity to receive such a guest. A 17th-century poet named Matthew Hale worried about this in a poem called “Christmas Day” (1659):

I have a room

‘Tis poor, but ‘tis my best, if thou wilt come

Within so small a cell, where I would fain [willingly]

Mine and the world’s Redeemer entertain;

[He’s speaking about his heart here as the place he might entertain the world’s Redeemer;

Then he describes sweeping up the dust and cleaning up the mess, just as we would if we expected a houseguest. The poet will even try to wash this “room”—with his own penitent tears:]

And when ‘tis swept and washed, I then will go,

And with Thy leave, I’ll fetch some flowers that grow

In Thine own garden, [these flowers being faith and love];

With those I’ll dress it up …

yet when my best

Is done, the room’s [still] not fit for such a Guest.

[Well, if we can’t make our lives and our souls fit dwellings to house the divine, who can? God. God can make us fit, the poet says:]

Thy presence, Lord, alone

Will make [an oxen] stall a court, a cratch [manger] a throne.

These days, it’s not very easy to believe that humanity is a fit habitation for the God of love and the Prince of Peace. It’s a sign of our sad times that Christmas got cancelled in Bethlehem this year. The war, you know. No liturgies in the Church of the Nativity, no pilgrims crowding Manger Square. They say Bethlehem is like a ghost town now.

Sixty years ago, the Catholic contemplative Thomas Merton, who was not blind to the atrocities committed in his own time, could still say that we “exist solely for this, to be the place God has chosen for the divine Presence. The real value of our own self is the sign of God in our being, the signature of God upon our being.” [i] The Word indelibly inscribed on our own hearts and souls!

Some—theologians, poets, mystics—go even further, insisting that the Word becoming flesh means that the whole world is “charged with the grandeur of God.” [ii] Maximus the Confessor, perhaps the greatest Byzantine theologian, put it this way in the 7th century:

“For having hidden Himself for us in the inner principles of existent things, [God] is correspondingly spelled out by each visible thing as if by letters. [The Divine] is wholly present in all together in the fullest possible way and completely in each individually, whole and undiminished.” [iii]

Contemporary songwriter Peter Mayer makes this point more simply:

When I was a boy in Sunday school, we would learn about the time

that Moses split the sea in two,

And Jesus made the water wine.

And I remember feeling sad miracles don’t happen still.

But now I keep track ‘cause everything’s a miracle:

Everything, everything, everything’s a miracle.…

This morning outside I stood and saw a little red-winged bird

Shining like a burning bush, singing like a scripture verse:

It made me want to bow my head …

‘cause everything is holy now.

Everything, everything, everything is holy now. [iv]

In other words, what happens in Bethlehem doesn’t stay in Bethlehem.

It wants to happen everywhere.

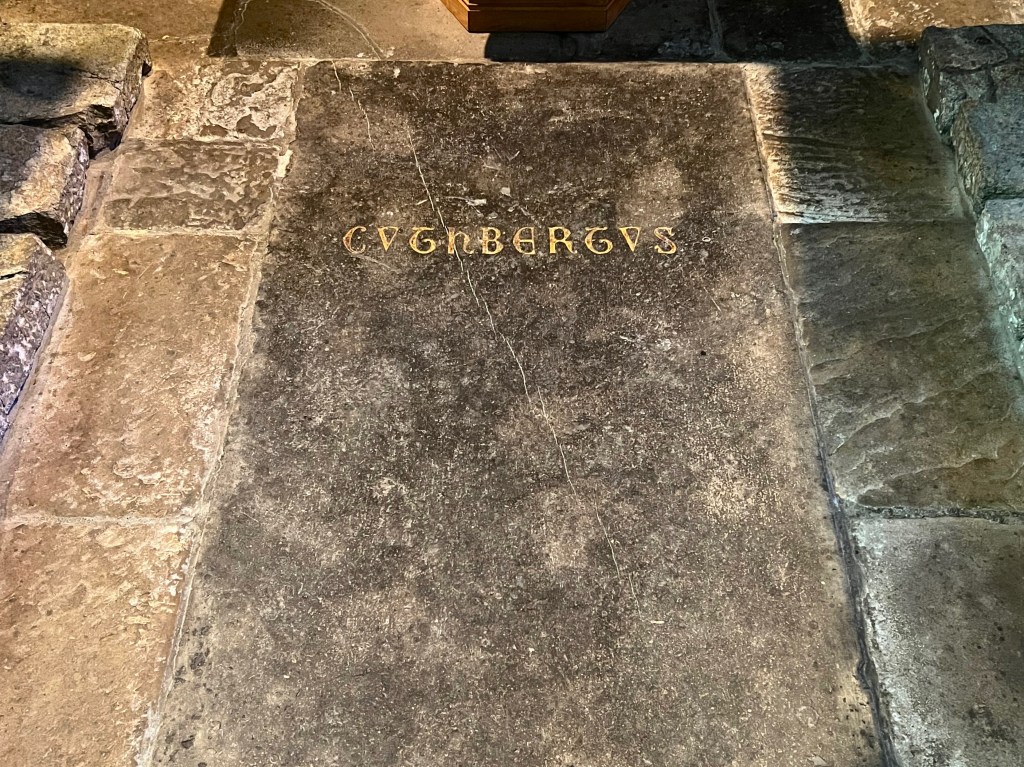

We might call this the Bethlehem effect—discovering the Word made “flesh” in the concrete stuff of our world, our stories, our very lives. The great Christian poet of the 4th century, Ephrem the Syrian, describes the Bethlehem effect in one of his poems. He begins by proclaiming his Christmas joy:

Blessed be the Child Who today delights Bethlehem.

Blessed be the Newborn Who today made humanity young again.

[Then he describes the effect this holy birth wants to have on us:]

On this day of the Humble One let us be neither proud nor haughty.

On this day of forgiveness let us not avenge offenses.

On this day of rejoicing let us not share sorrows.

On this sweet day let us not be vehement.

On this calm day let us not be quick-tempered.

On this day on which God came into the presence of sinners,

let not the righteous look down on any sinner.

On this day on which the Lord of all came among servants,

let the powerful bow down to the powerless.

On this day when the Rich One was made poor for our sake,

let the rich share their table with the poor. [v]

On that holy night in Bethlehem, our human nature was lifted up when God chose to be one of us, to live and die as one of us. And we in turn may now share in the divine life. We are still works in progress no doubt, but we are bound for glory. St. Paul put this so beautifully: “All of us,” he said, “all of us, with our unveiled faces like mirrors reflecting the glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the image that we reflect in brighter and brighter glory” (II Cor. 3:18).

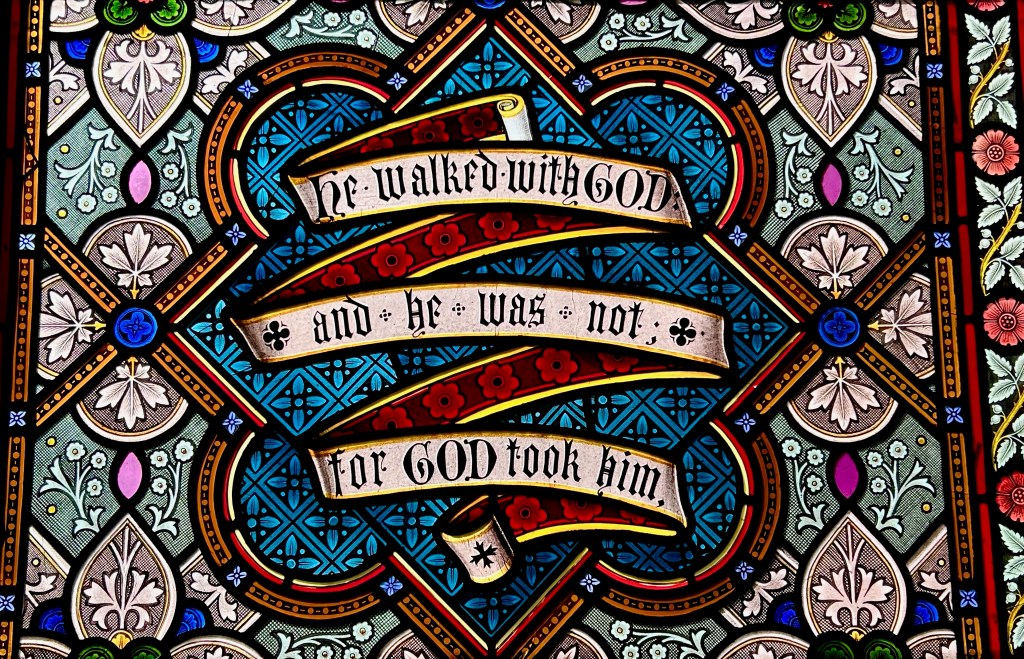

Another ancient theologian said it this way: “As they who behold the light are within the light and partake of its brightness, so they who behold God are within God, partaking of God’s brightness.” [vi]

They who behold the light are within the light and partake of its brightness. That’s the Christmas miracle! Our pale mirrors are made to contain the most impossible brilliance. And even when we turn away from the Light, the Light comes looking for us. No matter how shadowy the paths we have taken, the Light will find us, and fill us with divine radiance. That is our destiny, says the Child in the manger. To walk around “shining like the sun.” [vii]

However … Before we get too carried away with our glorious destiny, listen to a line from the Victorian poet Mary Elizabeth Coleridge. When she imagines coming to the stable, and seeing the babe in the manger, she says:

The safety of the world was lying there.

And the world’s danger. [viii]

The babe in the manger is the world’s danger? What does she mean? I think she is saying that giving our lives to the Holy One will change everything. It will change who we are, what we care about, and how we live. In other words, participation in the divine life (which is the only way to become fully human) is not just a matter of “walking around shining like the sun.”

It also means letting go of certain cherished things and taking up our cross. The story of the Incarnation is more than the beautiful new-born child away in the manger. The child will become a man, and he is going to ask some difficult things of us someday.

I don’t want to go very far down that road on Christmas Day. The twelve days of Christmas are a time for celebration and feasting, carols and good cheer, light hearts and extravagant hopes, joy and wonder, and lots of love. But I do want to share a poem by Luci Shaw, a Christian writer now in her 90s. She reminds us that the lovely babe of Bethlehem is going to grow up, and that we’re going to have to grow up with him.

One time of the year

the new-born child

is everywhere,

planted in madonnas’ arms

hay mows, stables

in palaces or farms,

or quaintly, under snowed gables,

gothic angular or baroque plump,

naked or elaborately swathed,

encircled by Della Robia wreaths,

garnished with whimsical

partridges and pears,

drummers and drums,

lit by oversize stars,

partnered with lambs,

peace doves, sugar plums,

bells, plastic camels in sets of three

as if these were what we need

for eternity.

But Jesus the Man is not to be seen.

We are too wary, these days,

of beards and sandalled feet.

Yet if we celebrate, let it be

that He

has invaded our lives with purpose,

striding over our picturesque traditions,

our shallow sentiment,

overturning our cash registers,

wielding His peace like a sword,

rescuing us into reality

demanding much more

than the milk and the softness

and the mother’s warmth

of the baby in the storefront creche,

(only the [grown] Man would ask

all, of each of us)

reaching out

always, urgently, with strong

effective love

(only the [grown] Man would give

his life and live

again for love of us).

Oh come, let us adore him—

Christ—the Lord. [ix]

Okay, I can’t leave you there, not on Christmas Day. So let me end on a note of wonder, with a poem by G. K. Chesterton. It was sung at this year’s Christmas Eve Lessons and Carols at Kings College, Cambridge. [x]

The Christ-child lay on Mary’s lap,

His hair was like a light.

(O weary, weary were the world,

But here is all aright.)

The Christ-child lay on Mary’s breast,

His hair was like a star.

(O stern and cunning are the kings,

But here the true hearts are.)

The Christ-child lay on Mary’s heart,

His hair was like a fire.

(O weary, weary is the world,

But here the world’s desire.)

The Christ-child stood at Mary’s knee,

His hair was like a crown.

And all the flowers looked up at Him,

And all the stars looked down.

This sermon was preached at St. Barnabas Episcopal Church on Bainbridge Island, Washington, on Christmas Day, 2023.

[i] Thomas Merton, “A Letter on the Contemplative Life” (August 1967), in Lawrence S. Cunningham, ed., Thomas Merton: Spiritual Master—The Essential Writings (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1992), 425.

[ii] Gerard Manley Hopkins, “God’s Grandeur.”

[iii] Maximus the Confessor (c. 580-662). Quoted in Nikolaos Loudovikos, A Eucharistic Ontology: Maximus the Confessor’s Eschatological Ontology of Being as a Dialogical Reciprocity (Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Press, 2010), 125.

[iv] Peter Mayer, “Holy Now.”

[v] Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306-379), Hymns on the Nativity (trans. Kathleen E. McVey, Paulist Press, 1989), adapted from a citation in Wendy M. Wright, The Vigil: Keeping Watch in the Season of Christ’s Coming, Nashville, TN: Upper Room Books, 1992), 95-96.

[vi] Irenaeus (c. 130-202), Against Heresies, IV.20.

[vii] The phrase is from Thomas Merton’s famous revelatory experience at the corner of Fourth & Walnut in Louisville in March 1958. “And if only everybody else could realize this! [the dignity of humanity conferred by the Incarnation]. But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.”

[viii] Mary Elizabeth Coleridge (1861-1907), “Salus Mundi.” She was the great-grandniece of Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

[ix] Luci Shaw, “It is as if infancy were the whole of incarnation,” quoted in Sarah Arthur, ed., Light Upon Light: A Literary Guide to Prayer for Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2014), 125-126.

[x] G. K. Chesterton, “A Christmas Carol,” was sung in a lovely setting by John Rutter on the 2023 Lessons and Carols from Kings College, Cambridge, during the annual live BBC broadcast with which I begin every Christmas Eve at 7 a.m. Pacific Time.