The evil and the armed draw near;

The weather smells of their hate

And the houses smell of our fear.

— W. H. Auden, For the Time Being

“ … because all you of Earth are idiots!”

— Plan 9 from Outer Space (Ed Wood, 1957)

How bad is it, anyway? In the first hours of the new Amerika last Tuesday, the original Planet of the Apes (1968) came to mind. Finding a half-buried Statue of Liberty on a deserted beach, space-and-time traveler Charlton Heston realizes he has not landed on some distant planet, but on his own earthly home, where humanity has evidently committed nuclear suicide. Literally pounding the sand, he cries out to his long-vanished fellow mortals, “You really, finally, did it! You maniacs! You blew it up! Damn you! God damn you all to hell!”

In the Year of our Lord 2024, a decisive majority of Americans have chosen to blow up democracy, the rule of law, the common good, civil liberty, women’s rights, health care, international stability, public sanity, and our last hopes of staving off climate apocalypse. Did they know what they were doing? I confess to zero interest in their motivation at this point. Their decision, measured by its inevitable consequences, was neither rational nor moral. The harm it will do is immeasurable. Even if they thought they were trying to make a point about their personal economic pain, the mad embrace of a fascistic, unstable sociopath and the MAGA dream of demolishing the American experiment—not to mention the livability of our planet—will impose a price none of us can afford.

The American minority, meanwhile, has spent the past week trying to cope with the shock and the horror of the Antichrist’s second coming (I use that name not in a mythical sense, but in a moral one, describing the Trump who in every respect is against the way of Jesus).

Some have engaged in second-guessing the Democratic campaign, as if putting the argument differently could have penetrated the thick shields of delusion and hate erected by right-wing propagandists and their carefully crafted algorithms. Some have sought comfort in the long view, looking toward the distant horizon where hope and history will someday rhyme. Some see the moment as a sobering diagnosis of our national maladies, putting an end to further denial. There’s no use pretending we’re still healthy. Some are tuning out, or contemplating flight to saner climes. Some, sadder and wiser, are vowing to carry on the fight for the common good. God help them.

Many people have been passing poems around on social media, lighting candles of gentleness and peace for one another in this dark night. I have taken comfort in these tender gestures, offered like balm in Gilead for the sin-sick soul. But I also have found myself browsing post-WWII poems that register the shock of brutal conflict. “The Last War” by Kingsley Amis (1948) touched a chord in me with its opening line: “The first country to die was normal in the evening.” By morning it was disfigured and dead

The poem narrates a kind of Agatha Christie murder story in a country house. No one, in the end, survives the weekend. When the sun (the light of Reason? the eye of God?) shows up to survey the damage and “tidy up,” he is unable to separate “the assassins from the victims.” Sickened by the folly and horror of human self-destruction, the sun goes back to bed. The last two stanzas begin with the sound of gunfire and end with a deathly quiet:

Homicide, pacifist, crusader, tyrant, adventurer, boor

Staggered about moaning, shooting into the dark.

Next day, to tidy up as usual, the sun came in

When they and their ammunition were all finished,

And found himself alone.

Upset, he looked them over, to separate, if he could,

The assassins from the victims, but every face

Had taken on the flat anonymity of pain;

And soon they’ll all smell alike, he thought, and felt sick,

And went to bed at noon.

The sense of recognition I felt in reading the poem oddly eased my post-election malaise. Though I dwell in the valley of the shadow, I’m not alone. Like Dante in hell, I’ve got a good poet for company.

Well, what now? If there were ever a time demanding religious imagination—the ability to see resurrection light even on Good Friday—this is it. Such envisioning will be one of the ongoing tasks of The Religious Imagineer. But we can’t just leap into Easter. We must first do our time at the foot of the cross, living in solidarity—and risk?—with the victims and the vulnerable, tuning our hearts to the bells that toll for every human tear:

Tolling for the luckless, the abandoned and forsaked,

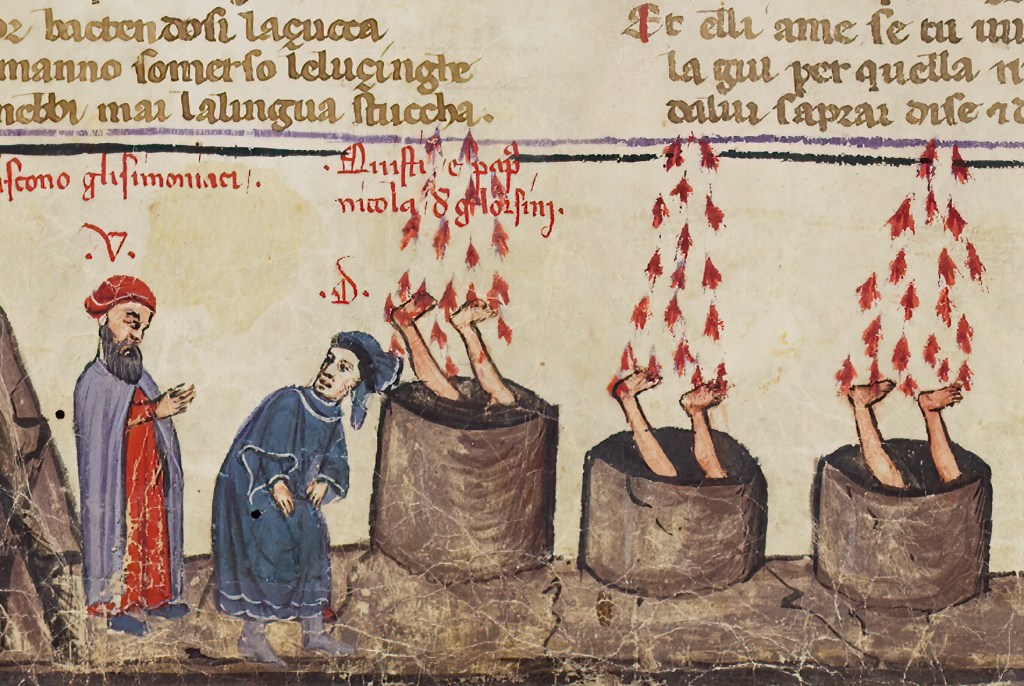

Tolling for the outcast, burning constantly at stake …

Tolling for the aching ones whose wounds cannot be nursed,

For the countless confused, accused, misused, strung-out ones and worse,

And for every hung-up person in the whole wide universe. [1]

I feel blessed to be in Christian community during this time of trial. It is better to hold hands than clench fists. It restores the soul to share our griefs and voice our hopes in sacred discourse and common prayer. Preachers are encouraging our renewed commitment to the Baptismal Covenant: to persevere in resisting evil; seek and serve Christ in all persons; strive for justice and peace among all people; and respect the dignity of every human being.[2] Pastors, meanwhile, are reminding us to love those who voted against most of those things.

(I confess to my own struggle with the Christly precept of loving the haters. Yes, we all fall short, but the so-called Christians cheering the triumph of our basest impulses are, IMHO, falling short with unseemly enthusiasm. As Henry James noted, “when you hate you want to triumph.”) [3]

Many of us, like the desert monks of Late Antiquity, are feeling the need to go on retreat from the public square, to hush the noise and attend the still small voice of holy wisdom. Our spiritual practices seem more necessary than ever.

For me over the past week, that has taken the form of Daily Offices, running, watching the birds in the garden, reading Henry James, a Monteverdi concert, and a splendid evening of Balanchine works by the Pacific Northwest Ballet. I have also been fasting from political news, limiting myself to a small amount of reflective commentary from trusted sources. Such self-care through withdrawal from the fray is “meet and right so to do.” But unless we are contemplatives whose job is to provide for the rest of us what Jesuit activist Dan Berrigan called “large reserves of available sanity,” we can’t stay in the desert forever.

Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann has responded to the election with a fine reflection on Elijah’s flight from the danger and exhaustion of public justice-making to the solitude and safety of the holy mountain. After a while, God tracks him down to ask, “What are you doing here, Elijah?”

“Go back to your proper place; you can linger here in self-pity only so long and then you must remember your call and perform your responsibility.” So Elijah is freshly dispatched back to his dangerous work. He is dispatched by the one who has lordly authority for him. The only assurance he is offered is that there are others—7000—who stand alongside in solidarity.[4]

We are not alone. God is with us. The night after the election, some of our local parish church gathered for Evening Prayer, with generous pauses for quiet resting in the Divine Presence. When words fail, let silence speak. Afterward, we had a deep and earnest conversation about the effect of the election on our hearts, minds, and bodies. The empowering richness of that exchange, a gift of the Holy Spirit, raised us from the depths to remember our vocation as God’s friends: to plant the seeds of resurrection amid the blind sufferings of history.

Let me close with an encouraging story from the desert monks.

The disciple of a great old man was once attacked by the demons within him. The old man, seeing it in his prayer, said to him, ‘Do you want me to ask God to relieve you of this battle?’ The other said, ‘Abba, I see that I am afflicted, but I also see that this affliction is producing fruit in me; therefore ask God to give me endurance to bear it.’ And his Abba said to him, ‘Today I know you surpass me in perfection.’” [5]

Throughout this time of trial and affliction, God grant each of us, and our communities, the endurance to bear what we must bear, and do what we must do, that our lives may prove both faithful and fruitful in due season.

[1] Bob Dylan, “Chimes of Freedom,” from Another Side of Bob Dylan (Columbia Records, 1964).

[2] From the Baptismal Covenant, Episcopal Book of Common Prayer (1979).

[3] Henry James, The Ambassadors (New York: Modern Library, 2011), 427.

[4] Walter Brueggemann’s reflection on I Kings 19, “Beyond a Fetal Position,” Nov. 7, 2024 on Church Anew: https://churchanew.org/brueggemann/beyond-a-fetal-position

[5] Cited in John Moses, The Desert: An Anthology for Lent (Norwich: The Canterbury Press, 1997), 62.