O come, O come Emmanuel,

and ransom captive Israel.

Once upon a time, worshippers entered their church on the Second Sunday of Advent to find a great wall between themselves and the sanctuary. The beautiful mosaics, the richly colored marble walls, and the magnificent carved Christ above the high altar were all hidden from view by this strange iconostasis, made from front pages of the Los Angeles Times. Instead of the images of holy men and women that adorn a traditional altar screen, there were banner headlines screaming catastrophe and mayhem.

When the assembly was seated, a mime came up the aisle to stand before the wall, searching for some way through it. His movements and gestures indicated perplexity, frustration, and finally discouragement. Then a voice from beyond the wall cried out,

Jerusalem, turn your eyes to the east,

see the joy that is coming to you from God. (Baruch 4:36).

Responding to the voice, the mime tore a small hole in the wall, and peeked through. He seemed entranced by what he saw.

The voice continued:

Take off the garment of your sorrow and affliction, O Jerusalem,

and put on forever the beauty of God’s glory. (Baruch 5:1)

The mime began to tear down the wall, encouraging others to join him. One by one, people rose from their pews to rip down the veil “of sorrow and affliction,” until the beauty of God’s sanctuary was finally revealed.

This simple but powerful ritual, the prelude to a eucharist I curated forty years ago at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Los Angeles, comes to mind whenever I hear that passage from Baruch in the December lectionary. It’s what we pray for each Advent from our place on this side of the wall: Good Lord, deliver us. Stir up your power. Tear down the wall between us. Show us your glory.

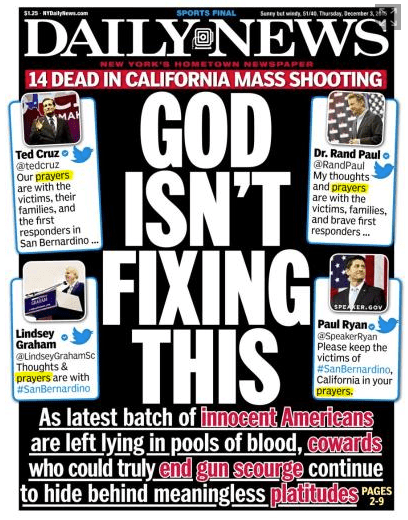

That wall of headlines reflected my ongoing interest in connecting Advent themes with the news of the world. The WTO protests in Seattle (1999) and the Occupy Movement (2011) both coincided nicely with Advent, mirroring its prophetic themes of judging the present order with the hope and vision of something better.[i] And just last week, the front page of the New York Daily News supplied a marvelous Advent provocation. By noon, it had 11 million Facebook views, and 74,000 shares.

The headline was a sharp rebuke to the shameless politicians who promise prayers for the victims of gun violence while refusing to do anything about the guns. Calling them “cowards who could truly end gun scourge” but instead “hide behind pious platitudes,” the newspaper offered a blunt theological assertion: “God isn’t fixing this.”[ii]

The daily office Old Testament readings for early Advent, calling the world to account for its evils, say much the same thing. To those who refuse to “renounce the dictates of our own wicked hearts,”[iii] the prophets imagine God declaring, “You made your own bed. Now lie in it.” (Thankfully, the prophets always redeem their rants in the end with comforting decrees of mercy and salvation).

However, the Lieutenant Governor of Texas was not comfortable with the Daily News’ riff on the old biblical idea that God sometimes gets fed up with human folly. His photoshopped revision was posted on Facebook and Twitter.

Of course this clueless retort (note the unfortunate juxtaposition of the headline with the red banner above it) did not actually answer the question of whether – or how – God acts in the world to “fix” things. It was just a clumsy attempt by a presumed gun lover to change the subject. Platitudes about prayer in the abstract are safe because they have no consequences, unlike real prayer, which always implicates the petitioner in a process of change and action. If we pray for an end to gun violence, we obligate ourselves to do all in our power to reduce it. Prayer is a call for action; it politicizes what we pray for. Prayer is not simply leaving things up to God. It is an act of volunteering to be part of God’s solution.

But is there such a thing as God’s solution? Does God – can God – fix things? It is not a question with a clear and simple answer. Human freedom has thrown a monkey wrench into the story of the world, while God has surrendered absolute control of the narrative. If we make a mess of things, God is not an indulgent parent rushing in to cover for us. We don’t get to multiply our weapons and then wonder why God allows so much violence.

So where does that leave us? In the Advent section of his Christmas Oratorio,[iv] W. H. Auden describes a closed-in, godless world where hope is absent.

Alone, alone about a dreadful wood

Of conscious evil runs a lost mankind …

The Pilgrim Way has led to the abyss.

But what if we are not alone? What if there is a God who can make the abyss into a way? What if an unexpected future is breaking through the walls of our self-made prison? The Advent message is to embrace this hope, as we take off the garments of sorrow and affliction to welcome the God of joy into our midst.

Whatever the “solution” (salvation) may be in the tangled histories of the world and the soul, it is a long-term, sometimes excruciating, process, requiring honest engagement with the consequences of human sin in acts of confession, repentance, reconciliation, justice, healing, sacrifice, and transformation. And I submit that these are not simply things we do with God, as though God were only a helper from the outside. They are things we do in God, or God does in us, as our own intentions and actions become the embodiment – the incarnation – of divine purpose.

So yes, I believe that God is fixing the world, but not in the short run. And not without us.

[i] I preached on both these events at the time, with mixed results. Some were not so ready to find traces of God in social movements which trouble the powers-that-be. One church subsequently banned me from its pulpit for being too “partisan.” Guilty as charged.

[ii] New York Daily News, December 3, 2015.

[iii] Baruch 2:8

[iv] W. H. Auden, For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio, in Collected Poems, ed. Edward Mendelson (New York: Random House, 1976), 273