I have written repeatedly about major moments of the year such as Christmas, Easter and New Year’s Eve, but the only individual person (other than Jesus) to make repeated appearances on this site is the seventeenth-century Anglican poet-priest, George Herbert (1593-1633). I enjoy many poets, but Herbert’s psalmic verse is a regular part of my prayer life, and I am particularly partial to priests for whom art is a spiritual practice.https://jimfriedrich.com/2015/02/27/heart-work-and-heaven-work/

After overviews of his life and work (Heart Work and Heaven Work and “Flie with Angels, Fall with Dust”), I have looked at particular poems (“Denial,” “Virtue,” “Time” and “Life”) in subsequent posts on his feast day (February 27). Having established something of a tradition, let us honor “the holy Mr. Herbert” by considering another of his poems.

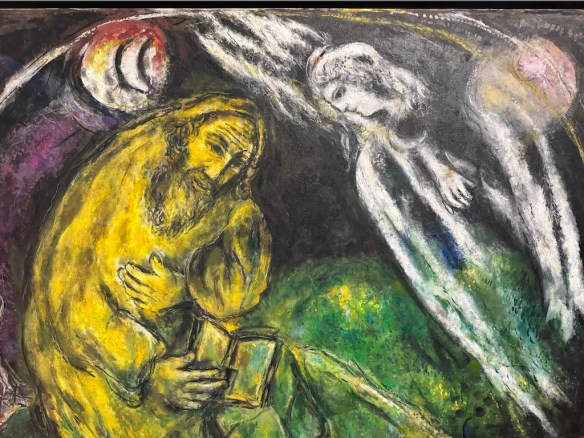

In “Mans medley,” the poet tests the tension between the earthly and heavenly elements in humanity’s hybrid nature. Just as a musical medley is composed of contrasting parts, so are we a unique blend of animal and angel. When Herbert was seven years old, playgoers first heard Hamlet pondering this paradox of human existence: “how like an angel in apprehension” is this “quintessence of dust”. Ten years after Herbert’s poems were published, Sir Thomas Browne wrote that “we are only that amphibious piece between a corporall and spirituall essence, that middle forme that links these two together” and “unites incompatible distances.” [i]

Mans medley

Hark, how the birds do sing,

And woods do ring.

All creatures have their joy: and man hath his.|

Yet if we rightly measure,

Mans joy and pleasure

Rather hereafter, then in present, is.To this life things of sense

Make their pretence:

In th’ other Angels have a right by birth:

Man ties them both alone,

And makes them one,

With th’ one hand touching heav’n, with th’ other earth.In soul he mounts and flies,

In flesh he dies.

He wears a stuffe whose thread is course and round,

But trimm’d with curious lace,

And should take place

After the trimming, not the stuffe and ground.Not that he may not here

Taste of the cheer,

But as birds drink, and straight lift up their head,

So he must sip and think

Of better drink

He may attain to, after he is dead.But as his joyes are double;

So is his trouble.

He hath two winters, other things but one:

Bothe frosts and thoughts do nip,

And bite his lip;

And he of all things fears two deaths alone.Yet ev’n the greatest griefs

May be reliefs,

Could he but take them right, and in their wayes.

Happie is he, whose heart

Hath found the art

To turn his double pains to double praise.

The poem begins with a cheerful celebration of creation: Birds sing, forests ring, and all creatures, humans included, “have their joy.” But difference soon declares itself: below and above, material and spiritual, this life and the next. Only humans partake in each of the oppositions, with “th’ one hand touching heav’n, with th’ other earth.” This is a great privilege. The human alone “ties them both” and “makes them one,” but as the next verse reminds us, our mixed nature is also a problem. We may “flie with angels” as Herbert says in another poem, but we also “fall with dust.”[ii] In soul we mount and fly, but in flesh we die.

“Medley” is related to “motley,” and the image in verse 3 of being clothed in an awkward mixture of fine and coarse materials illustrates our chronic discomfort with humanity’s hybrid nature. To resolve the clashing colors of our mortal outfit, some have sought to suppress, downgrade, or disregard either the earthly or the heavenly. But Herbert seeks to harmonize them in the human medley. Let our joys be “double,” that we may “taste of the cheer” in our sensory existence while continuing to cultivate our taste for the “better drink” of spiritual reality.

The verse about the sipping birds is my favorite part of the poem. Unlike the generalized trope of singing birds in the poem’s first line, the birds in verse 4 are keenly observed in a way that was rare until the Romantics and naturalists of later centuries. The birds don’t keep their beaks in the water until they’re done, but follow each sip with a lifting of the head. Here Herbert takes a homely image from the visible world and makes it a lively spiritual metaphor. Like the birds, we should not gulp down reality without giving it our proper attention. We must learn to “sip and think,” alternating our experience with thoughtful reflection.

And from there the meanings multiply. The “better drink” evokes the sacred wine of the Eucharist, while also recalling the water Jesus changed into wine at the Cana wedding feast. Sip and think. Sip and think. Could that be the essence of spiritual practice?

Our mortality is touched upon in verse 3 (“In flesh he dies”) and verse 4 (“after he is dead”), but verse 5 stops to face our fate directly. As both physical and spiritual creatures, we alone fear “two deaths”—the death of the body and the death of the soul. As dwellers in a secular age, some no longer worry about the fate of body and soul in the afterlife, but is anxiety over a failing body, a shriveled soul or an emotionally dead heart any improvement on the medieval fear of hell? There are many kinds of death, but the inward ones may be the worst.

Herbert doesn’t leave us there. As he warns in his manual of advice for country parsons, “nature will not bear everlasting droopings.” We need to stand on the rock of hope, and remember joy. “Yet ev’n the greatest griefs,” he says, “May be reliefs, / Could he but take them right … / Happy is he whose heart / Hath found the art / To turn his double pains to double praise.”

We may wonder what it means specifically to “take them right.” We could all use some detailed instruction in the art of turning pain into praise, given the rapid escalation of pain in our collective life by a heartless coterie of dead souls. Herbert doesn’t spell it out in this poem, but turning pain into praise is a major theme in his work.

In both our personal spiritual journeys and our collective project of repairing the world, we must practice many virtues: patience, persistence, resistance, constancy, solidarity, compassion, humility—and, crucially, faith, hope and love—if we are to keep moving toward the light. And it is my firm conviction that the antidote to despair is trust in what I would call divine intention: the abiding and faithful Mystery whose desire is the flourishing of creation. That doesn’t mean everything goes perfectly. The Cross is planted deep in human history. But God will not leave us comfortless. The divine Yes has more future in it than a billion Nevers. Here’s how Herbert says it:

I knew that thou wast in the grief,

To guide and govern it to my relief,

Making a scepter of the rod:

Hadst thou not had thy part,

Sure the unruly sigh had broke my heart. [iii]

[i] Sir Thomas Browne, Religio Medici xxxiv (1643).

[ii] George Herbert, “The Temper (I).”

[iii] Ibid., “Affliction (III).”