I spent only one year in a world without nuclear weapons. My first birthday fell on July 16, 1945, the day of the initial atomic bomb test in New Mexico. A few weeks later, my country used the bomb to extinguish countless human lives on the Feast of the Transfiguration. With Transfiguration falling on a Sunday as Oppenheimer is playing in the theaters, a few comments are in order.

In an interpretive retelling of the Transfiguration by a 17th-century Anglican bishop, Moses and Elijah discuss the paradoxical mixture of evil and glory that permeates the Way of the Cross:

A strange opportunity … when [Jesus’] face shone like the sun, to tell him it must be blubbered and spat upon;… and whilst he was Transfigured on the Mount, to tell him how he must be Disfigured on the Cross! [i]

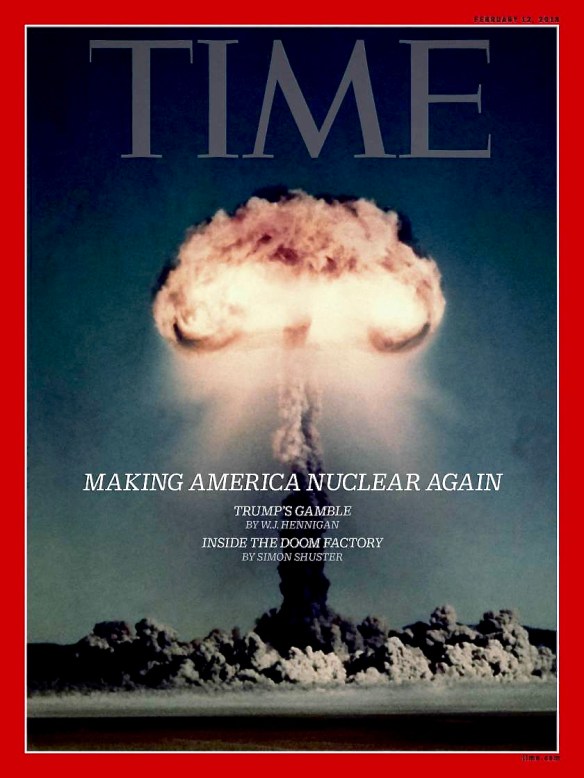

In the twentieth century, that paradox was tragically deepened when we dropped the atomic bomb at Hiroshima on the Feast of the Transfiguration. Two kinds of light, diabolic and divine, contending forever after for the soul of this world. Whose world is it, anyway? To which light do we belong? To which light do we pledge our allegiance?

In his novel Underworld, Don DeLillo chillingly mixes and confuses the primal images of divine and diabolical light when a nun, swept out of her conscious self into the informational totality of the Internet, has a visionary experience on a website devoted to the H-bomb:

She sees the flash, the thermal pulse . . . . She stands in the flash and feels the power. She sees the spray plume. She sees the fireball climbing, the superheated sphere of burning gas that can blind a person with its beauty, its dripping christblood colors, solar golds and red. She sees the shock wave and hears the high winds and feels the power of false faith, the faith of paranoia, then the mushroom cloud spreads around her, the pulverized mass of radioactive debris, eight miles high, ten miles, twenty, with skirted stem and platinum cap.

The jewels roll out of her eyes and she sees God . . . .

No, wait, sorry. It is a Soviet bomb she sees . . . . [ii]

I’ve not yet seen Oppenheimer, the film about the creator of the atomic bomb. But I was struck by this paragraph in a review by Adam Mullins-Khatib:

“Oppenheimer … is a searing portrait of a man plagued by visions of a world that can’t be seen, a theoretical world composed of the literal particles of his ideas. Driven by an unyielding need to bring his visions to light, J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) struggles with the notion of bringing theory into practice … It’s a film about the creation of something not before seen and the consequences this entails.” [iii]

Something not before seen and the consequences this entails. That could describe both the coming of Christ and the invention of the Bomb: each brought into the world something not before seen, manifested in a moment of blinding brilliance. And each has had enormous consequences which are still very much with us. But only one of them is the Light eternal, pure brightness of the everlasting Love who loves us.

To paraphrase the divine Voice in Deuteronomy 30:19,

This day I set before you life and death, blessing and curse,

the light eternal and the light infernal.

Choose life.

Or else.

In 1944, one year before Hiroshima, Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky, wrote these words:

“We live in a world of suffering, a world broken and disintegrated, in which Christ’s Transfiguration uncovers reality and reveals to our skeptical minds a new humanity that has either entered into the light of the Risen One or is still called to do so … [W]e need to put on a robe of light, the apparel of those who live without fear, since they have already conquered death and the multiple anxieties associated with it.” [iv]

In this troubled and darkened age, that is exactly how the friends of God must live.

Let us put on the robe of light,

and live without fear.

.

[i] Bishop Hall Joseph Hall, Contemplations upon the principal passages of the Old and New Testaments, 1612-28, found on Google Books, p. 383.

[ii] Don DeLillo, Underworld (New York: Scribner, 1997), 825-6.

[iii] Adam Mullins-Khatib, Chicago Reader, July 26, 2003: https://chicagoreader.com/film/review-oppenheimer/

[iv] Vladimir Lossky, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2002, Originally published in French in 1944)), 151, 244.