Advent is not just a season of quiet waiting.

It is also a time of protest and vision.

As the election consequences unfold, Advent seems less a ritual preparation for Christmas than a realistic description of where we find ourselves in a darkening world. Pitting hope against despair, Advent calls us to “cast away the works of darkness and put on the armor of light.” My last post proposed 7 Spiritual Practices for the Time of Trial. I want to follow that by revisiting a post from November 2014, an Advent manifesto which seems even more timely today.

When I was 8 years old, I read in LIFE magazine that in so many millions of years, the sun would burn out and life on earth would cease. This worried me, so I asked my parents, “If the world is going to end, how come we say “world without end” when we pray?” And they told me what the Bible says, that heaven and earth may pass away, but God remains. That relieved some of my anxiety, but I still wasn’t sure I liked the idea of the world ending, even if God was in charge.

Of course the world ends all the time. When I moved from California to Puget Sound in the 1990’s, my first Northwest winter felt like a biblical apocalypse: the sun was darkened and the moon gave no light.

Who among us has not seen their world end? Adolescents exiled from childhood. Black teenagers robbed of their future. Elders deprived of their health. Unemployment …retirement …divorce … the death of a parent, a spouse, a child — in every one of these, a world comes to an end.

For anyone who has known serious loss, this is more than metaphor. The experience of grief can be so total and unrelenting that you can’t see anything beyond it. You can’t imagine the future. It feels like the end of the world.

The stars are not wanted now: put out every one;

Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun;

Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;

For nothing now can ever come to any good. [i]

W.H. Auden was invoking apocalyptic metaphors to express personal loss, but shared, public worlds also come to an end. As in 1789, or 1914. The Holocaust. Hiroshima. 9/11.My Lord, what a morning, when the stars begin to fall.

But why bring up such dreary stuff on this first day of the new Christian year? Shouldn’t we be breaking out the party hats, blowing horns and shouting “Happy New Year?” The wisdom of the Advent season is that it never begins with “A Holy Trinity Production,” or “The Creator of the World Presents.” No, it always opens with “The End.” Advent knows that every beginning involves some kind of ending. In this season’s Scripture, preaching and prayers, the present arrangements of collective and personal life are judged and found wanting. God’s imagination is far too rich and fertile to settle for our barren and diminished versions of human possibility.

Selfishness, greed, consumerism? Fear, racism and violence? Poverty, militarism, war, environmental degradation? That’s the best we can do? Really? God must be saying, “Come on, people. I made you a little lower than the angels, and this is what you came up with?”

George Eliot said “it is never too late to become what you might have been.” But to get to that “might have been” requires an Exodus into the wilderness beyond the way things are; an Exodus beyond even the best we can imagine for ourselves, into a place of unknowing, where only God possesses the language to speak our future into being.

So much of what we hear and pray and sing in Advent is profoundly disruptive. Bob Franke’s great Advent song, “Stir up your power,” gets right to it in the first line: This world may no longer stand. We are meant to be unsettled, to be driven beyond our narrow boundaries, our constricted realities, toward a beckoning horizon. The Christian life is a perpetual series of departures for a better place.

The world as it is – the world of racial hatred and toxic violence and economic injustice and perpetual war and addictive consumerism and pollution for profit and all the other evils which poison our common life – this world has no future in the emergent Kingdom of God.This world may no longer stand.

But the story doesn’t stop there. In my end is my beginning.[ii] Even when we have gone far astray, even when our story seems over, God remains deeply present in the processes of creation, tenderly leading and luring us into newness of life, making a way where there is no way, opening doors that none can shut.

Advent people do not just wring their hands or shake their heads over the latest news from Ferguson or the Middle East. We work and pray for something better. What we can do on our own is limited, but when we offer our priorities and energies to the larger purposes of God, Love will have its way with us.

As the Christian mystic Hadewijch put it in the thirteenth century:

Since I gave myself to Love’s service,

Whether I lose or win,

I am resolved:

I will always give her thanks,

Whether I lose or win;

I will stand in her power. [iii]

It is not always easy to stand in Love’s power and keep the faith. In some situations it is almost unimaginable. Forty years ago the African-American author James Baldwin wrote:

To be an Afro-American, or an American black, is to be in the situation, intolerably exaggerated, of all those who have ever found themselves part of a civilization which they could in no wise honorably defend – which they were compelled, indeed, endlessly to attack and condemn – and who yet spoke out of the most passionate love, hoping to make the kingdom new, to make it honorable and worthy of life. [iv]

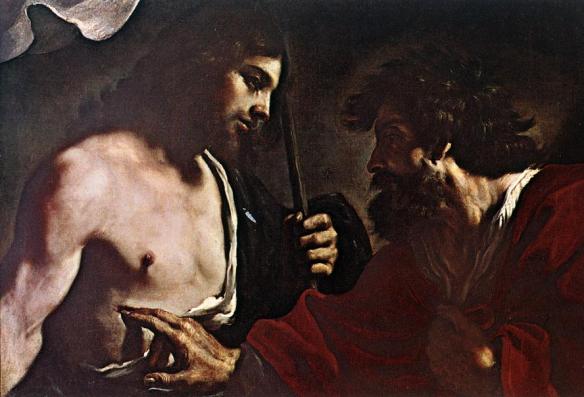

This passionate mixture of protest and love sounds a lot like the Old Testament prophets who permeate our Advent lectionary, making their prophetic plea for history to be broken open by divine justice:

O that you would tear open the heavens and come down …

to make your name known to those who resist you,

so that the nations might tremble at your presence! [v]

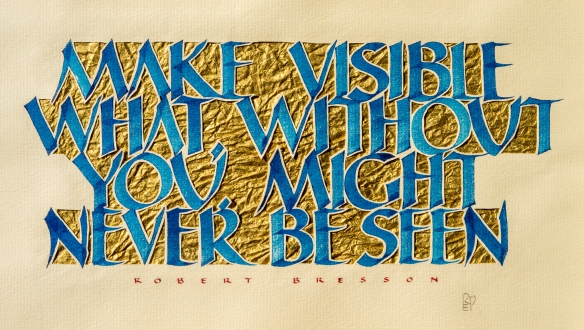

Advent is not just a season of quiet waiting. It is also a time of protest and vision. Advent announces an insurgency against the way things are, a revolution to scatter the proud, cast down the mighty, raise the lowly, gather the lost, free the captive, and bind up the brokenhearted. Advent re-imagines the world as paradise restored, a new heaven and new earth suffused with the peace of God.

this is the day of broken sky

this is the space of conflagration-breath

speaking border-trespass

this is the feathered swoop of heaven

on the wing of now …

forking lightning into language …

breaking god into prison …

breaking the truth from jail! …

This is the fire-tongued fork of holy-ghost howl

making love on the tongue …

spitting flames of reconciliation

in the sky of war

making messiah-praise out of the air itself!

this is pentecost in your head

like becoming what you never dared

for the first time and forever

This ecstatic prophecy is from a poem by Jim Perkinson. [vi] He was talking about Pentecost, but his theme fits Advent as well:

“the day of broken sky”

the earth in conflagration

God breaking into the prisons

the truth being set loose at last

and “the fire-tongued fork of holy-ghost howl

making love on the tongue …

making messiah-praise out of the air itself!”

And each of us, all of us, becoming what we never dared.

When Jesus tells us to stay awake, he is warning us not to sleep through the day of God’s coming. Stay alert. Pay attention. Don’t miss it! Become what you never dared. Shake off the sleep of complacency, the sleep of complicity, the sleep of despair. Awake and greet the new dawn.

Jan Richardson describes this dawning reality in her beautiful poem, “Drawing Near.” [vii]

It is difficult to see it from here,

I know,

but trust me when I say

this blessing is inscribed

on the horizon.

Is written on

that far point

you can hardly see…

Richardson accurately expresses the sense of distant horizon that prevents the dominant reality of the moment from closing in on us and locking us in. That reality wants to be believed as fixed and final, permanent and stable. But the horizon calls every finality into question, disrupting its stability with the boundlessness of divine possibility. The horizon draws our attention from what is given to what may yet be. Keeping our eye on the horizon, feeling its pull, is the spiritual practice of Advent. Richardson’s poem expresses the deep longing produced by the distance between the already and the not-yet.

And then the poet discovers what every pilgrim knows: the goal of our long journey is something that has already been inscribed deep within us even before our journey began. Even before the day we were born, we were marked as God’s own forever.

And that is where Advent ultimately leaves us – finding that the thing we have been seeking so long has been with us all the time – within us, and all around us. While we have been walking our Camino to the Promised land, our feet have already been on holy ground, every step of the way. And the God of the far horizon turns out to be the path as well, keeping us company as we stride deeper and deeper into the world.

So when Advent people talk about the end of the world, we are speaking about end in the sense of purpose rather than termination. The word “apocalypse” means “unveiling,” and the apocalypse in our future will not be an annihilation, but a revealing of the world’s ultimate purpose and destiny.

Yes, all the inadequate, incomplete versions of world will come to an end (some of them kicking and screaming!), but creation as it was intended will be restored, not discarded. Like a poet who creates a new language out of old words, Love will remake the ruins and recover the lost. And the Holy One who is the mystery of the world will be its light and its life forever.

This Advent faith is expressed memorably in a short story by British writer Carol Lake, “The Day of Judgment.” On the Last Day of the world, God sails into England aboard a new Ark. But instead of bringing history to a close and pronouncing judgment on everyone, God leaves the Ark to enter the city of Derby. Heading for the run-down inner city neighborhood of Rosehill, he joins the crowd at a local pub, a multi-ethnic mix of the working poor and the unemployed. And there God gets so caught up in being with these people that he loses track of time, and the Ark sails away without him, heading off for the horizon of eternity. As the story describes it:

The Ark is on the edge of the horizon now, its destination the heartlessness of perfection. Most of the inmates already know what they are going to find – endless fruit, endless harmony, endless entropy, endless endless compassion, black and white in endless inane tableaux of equality. It sails off to a perfect world; the sky has turned into rich primary colors and in the distance the Ark bobs about on a bright blue sea.” [viii]

Meanwhile, God is still in that Rosehill pub, in the very heart of imperfection. If you had walked in there, you would have had a hard time picking him out. He blended right in. But if you were paying attention, you might notice that there was now something different about Rosehill. The old non-descript streets and dilapidated buildings had taken on a strange beauty. Maybe it was the warm slant of afternoon light, but people were beginning to see their neighborhood in a new way. And their own faces, too, seemed to glow with an inner radiance, as if they were carrying a wonderful secret, tacitly shared with everyone around them, as if they suddenly knew there was more to life than meets the eye.

They were still poor, the world was still a mess, but something new was in the air, a spirit of change was awakening. And from that day on, the people of Rosehill found themselves becoming what they’d never dared, for the first time and forever.

[i] W.H. Auden, “Twelve Songs (ix)”, Collected Poems, ed. Edward Mendelson (NY: Random House, 1976), 120

[ii] T.S. Eliot, “East Coker,” Collected Poems 1909-1962 (London: Faber and Faber Ltd, 1974), 191

[iii] Hadewijch: The Complete Works, trans. Mother Columba Hart, Classics of Western Spirituality (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1980), 213

[iv] James Baldwin, No Name in the Street (NY: Dell, 1972), 194

[v] Isaiah 64:1-2

[vi] Jim Perkinson, “tongues-talk,” q. in Catherine Keller, On the Mystery: Discerning God in Process (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2008), 157-8

[vii] Jan Richardson, “Drawing Near” (http://adventdoor.com/2012/11/25/advent-1-drawing-near)

[viii] Carol Lake, Rosehill: Portraits from a Midlands City (London: Bloomsbury, 1989), 119