Good work is a way of living… it is unifying and healing. It brings us home from pride and despair and places us responsibly within the human estate. It defines us as we are, not too good to work with our bodies, but too good to work poorly or joylessly or selfishly or alone.

— Wendell Berry) [i]

Labor Day began in the late nineteenth century as both an homage to American workers (parade, speeches) and a time of re-creation (picnic, dance, fireworks). Congress declared it a national holiday in the aftermath of a contentious railroad strike in 1894, where 30 workers died in violent confrontations. It was hoped that honoring workers would ease tensions and foster social harmony. As the Department of Labor currently describes it, the first Monday in September “is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers. It constitutes a yearly national tribute to the contributions workers have made to the strength, prosperity, and well-being of our country.” [ii]

The holiday’s explicit homage to labor has long been overshadowed by its seasonal significance as the American farewell to summer—one last stretch of fun in the sun before the year gets busy again. But in our overworked culture, where the inbox follows you everywhere and vacations are a fraction of what Europeans enjoy, could we not make some time to reflect together about the nature of labor? What if churches were to revive the notion of Labor Sunday, where our tools could be blessed and the spirituality of work considered? [iii]

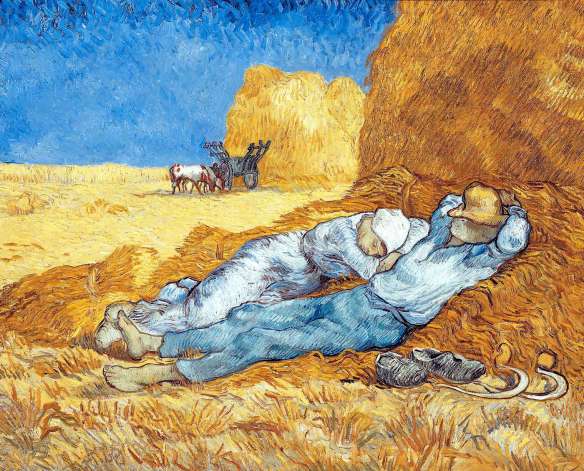

In the Bible, the pleasures of a perpetual weekend in Eden ended abruptly when God created Monday morning as a curse upon the first humans, who evidently needed to learn things the hard way. “By the sweat of your face” will you earn your daily bread,” said the Creator.[iv] The story was a way of thinking about the question, Why do we have to work so darn hard? Before the Fall, Adam and Eve were given light duties of tending the well-watered garden, more like an aristocrat’s hobby than the grueling subsistence farming bequeathed to their descendents.

Hard-working humans have been reminiscing ever since about the “happy Eden of those golden years.” [v] Stephen Duck, an eighteenth-century English poet-priest, voiced the complaint of the exploited farmworker.

Let those who feast at Ease on dainty Fare

Pity the Reapers, who their Feasts prepare …

Think what a painful Life we daily lead;

Each morning early rise, go late to Bed …

No respite from our Labour can be found;

Like Sisyphus, our Work is never done …[vi]

The justice issues arising around working conditions, exploitation, and economic inequality are themselves the shared work of any society worth its name. My ideal Labor Day would involve some serious community conversation—more listening than talking—about these things. But I would also be curious to explore the spirituality of work as well. Why do we do whatever we do? Does it give us joy? Does it matter?

An old Scottish drinking song provides a succinct answer in its praise of various occupations. The carpenter’s verse suggests the inner satisfaction of work well done, honors the process as well as the product, and celebrates the interdependence of the social world where each of us benefits from the labor of others:

Here’s a song for the carpenter, may patience guide your hand,

For the dearer your work to you, the longer it will stand.

And when the wind is at our door, we never will forget;

We’ve sung your praises many a time, and so will we yet. [vii]

Like our Creator, we are all makers and doers who enjoy the fulfillment of intentions and the solving of problems. It’s in our nature to see what needs to be done and then take a hand in making it so. We also find pleasure in the solidarity of labor, not only through our relationships with coworkers but also in the awareness of practicing a skill handed down by so many mentors and predecessors.

In an imperfect and often unjust society, not everyone has access to employment that delivers pleasure or meaning in itself, but one’s paying job may still be part of a larger labor which is absolutely worth doing, such as supporting a family or funding a future dream. Studs Terkel, who collected oral histories of countless Americans, believed that all of us long for meaningful work. “I think most of us are looking for a calling, not a job,” he said. “Most of us … have jobs that are too small for our spirit.” [viii]

Lewis Hyde makes a useful distinction between “work” and “labor.” Work is done by the hour, on the clock, usually for money. Its value is quantified, and has economic exchange value. Labor, on the other hand, keeps its own schedule, sets its own pace, and may include time off or even sleep as part of its process. Its social value may be clear, but its economic value is hard to quantify. Its product is not a commodity to exploit but a gift to share. “Writing a poem, raising a child, developing a new calculus, resolving a neurosis, invention in all forms—these are labors.” So are volunteer work, ministry, visiting the sick and the prisoner, gardening, personal soul work and “the slow maturation of talent.” [ix] Such labor is priceless.

Most of us have performed both work and labor, as well as hybrids which include elements of both. As Citizen Kane’s financial advisor said, “It’s no trick to make a lot of money, if all you want is to make a lot of money.” But the truer and nobler task is to cooperate with the Creator in repairing the world to make it a place of beauty, love and justice.

So my Labor Day question is this: Where and how can we do the labor to which we are called, the thing which étienne Souriau has called the “Angel of the work” [x]— that which gives us joy and blesses others?

There’s another verse in that Scottish song which thanks the singers who keep their voices clear:

For the world as you would have it be,

you sing with all your wit,

And ease the work of Providence,

and so will we yet.

In that spirit, I leave you with two such singers, Joan Baez and her sister Mimi Farina, who “ease the work of Providence” by voicing the universal human right to flourish: bread, yes, but roses too!

[i] Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America, q. in Karen Speerstra, ed., Divine Sparks: Collected Wisdom of the Heart (Sandpoint, ID: Morning Light Press, 2005), 520

[ii] Department of Labor website: https://www.dol.gov/general/laborday/history

[iii] This was instituted by churches as a companion to Labor Day, but has fallen into disuse.

[iv] Genesis 3:19

[v] John Clare, “Helpstone” (1809) q. in Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 10

[vi] Stephen Duck, “The Thresher’s Labour” (1730), in Williams, op. cit., 88

[vii] The original, “Sae Will We Yet,” is attributed to Walter Watson, but I believe the carpenter verse is a contemporary addition by Ossian’s Tony Cuffe. A fine version by Gordon Bok, Ann Muir, and Ed Trickett is here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h48Db_cvdDE

[viii] In Speerstra, op. cit., 519

[ix] Lewis Hyde, The Gift: Imagination and the Erotic Life of Property (New York: Vintage Books, 1979), 50

[x] étienne Souriau, q. in Isabelle Stengers, Thinking with Whitehead: A Free and Wild Creation of Concepts, trans. Michael Chase (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 464