“Nothing collapses more quickly than civilization during crises like this one [the French Revolution of June 1848]; lost in three weeks is the accomplishment of centuries. Civilization, life itself, is something learned and invented … After several years of peace men forget it all too easily. They come to believe that culture is innate, that it is identical with nature. But savagery is always lurking two steps away, and it regains a foothold as soon as one stumbles.”

— Sainte-Beuve [i]

When an inflamed crowd of Parisian citizens stormed the Bastille on July 14, 1789, the obsolete medieval fortress had long outlived its usefulness as an instrument of royal tyranny. It was destined for demolition, and a mere seven prisoners inhabited its dungeons when the crowd broke through the gates. A year later, Lafayette presented the key for the Bastille to President George Washington, honoring the quest for liberty by both countries. The key still resides at Washington’s Mount Vernon home.

Historians have suggested that the king’s capitulation to the political power of commoners (the ‘Third Estate’) on July 9 marks the true beginning of the French Revolution, but the bloody drama of Bastille Day proved a more potent symbol than the parliamentary negotiations being conducted at the king’s palace of Versailles. In any case, the once unthinkable destruction of the Ancien Régime had been decades in the making.

In The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748-1789, American historian Robert Darnton traces the growth of revolutionary sentiment as it was expressed in the Paris street: café conversations (often transcribed by police spies), underground gazettes and pamphlets, street songs, sidewalk speeches, public demonstrations and processions, and personal diaries. Eighteenth-century Paris had its own version of an information society, where “the ebb and flow of information among ordinary Parisians” was shared widely in cafés, marketplaces, wineshops, street corners and salons. [ii]

When the 72-year reign of Louis XIV ended in 1715, it was hard to imagine an alternative to absolute monarchy. His successor, Louis XV, would still be claiming dictatorial authority as late as 1766:

“In my person alone resides the sovereign power: from me alone my courts derive their existence and their authority, without any dependence and any division.” [iii]

In 1781, Louis XVI would tell his judiciary, “It is legal because I want it.” [iv] That’s the authoritarian creed. But by then, the game was up, and he was just whistling in the dark. A record of financial mismanagement, economic hardship, abuse of power, political corruption, and the ravages of poverty and hunger had by then called into question not only the effectiveness of the king and his government, but the legitimacy of the monarchy itself. Murmures (vocal grumbling about the regime) became part of daily life in Paris, and fed the printed complaints of the pamphleteers.

“Although the words were printed on paper, the messages of pamphlets flew through the air and mixed in the cacophony known as bruits publics [‘public rumors’]. Pamphlets were bruited about. They were read aloud, performed, applauded, rebutted, and assimilated in the talk that filled lieux publics [“public places”]. Readers also pondered tracts in the quiet of their studies, but when they went outside they encountered other Parisians, in marketplaces, along the quais, in the courtyard of the Louvre, on benches in the gardens of the Palais-Royal, the Tuileries, and the Luxembourg palace. Like smoke from thousands of chimneys gathering over the city, a climate of opinion gradually took shape.” [v]

It took half of the eighteenth-century to produce such a climate of opinion in France, a ”revolutionary temper” which was perfected, like tempered steel, through repeated heating and cooling. People would complain about this tax or that scandal, this outrage or that cruelty, but the tectonic shift from specific complaints to general discontent and clamor for change was a process of decades. Only when the climate of opinion attained sufficient density was it possible to imagine the impossible. Once revolution became conceivable, the leaps from absolute monarchy to constitutional monarchy to no monarchy at all were breathtakingly swift.

Revolution doesn’t necessarily require the refinements of political theory. By 1788, the high cost of bread by itself (like our egg or gas prices) was enough to elicit calls for radical change. One angry woman in a boulangerie was heard to say, “They should march on Versailles and burn the place down.” [vi] She was not alone, and by then the people of Paris were beginning to conceive of themselves as part of a movement, and act accordingly.

“Whether or not they followed the arguments of the theoreticians, Parisians were swept up in the conviction of becoming a nation, a sovereign body that would defy privileged orders and take charge of its own destiny. This way of constructing reality—the drawing of lines, the identification of a common enemy, the creation of a collective self-awareness—can be understood as a process of radical simplification. Although it had origins that went far back in the past, it came together with unprecedented force in 1788 and underlay a revolutionary view of the world: us against them, the people against the grands, the nation against the aristocracy.” [vii]

I could not read Darnton’s illuminating account without thinking of my own deeply troubled country. Although there are of course countless dissimilarities between 18th-century France and 21st-century America, some parallels got me thinking.

First of all, I found the accounts of a Paris alive with ardent conversations about public life to be inspirational. There was an urgency and a passion which feels lacking in America’s current collective consciousness. “Everyone writes, everyone reads,” said one of those pre-revolutionary Parisians. “Even the coachman reads the latest work on his perch,” said another. “Every person down to domestic servants and water carriers is involved in the debating.” [viii] But in America, 2025, while we may consume volumes of news in private, most of us carry on as if life is pretty much normal, even as our would-be dictator dispatches masked thugs to terrorize our communities, trains the military to act as his personal army, and builds concentration camps to torture and disappear his “enemies.”

Like 18th-century Paris, we need to converse with one another in earnest, employing a reliable flow of factual information and strategic thought to shape a collective consciousness for the common good. The forces of tyranny and greed have worked for decades to create its opposite, a seductive web of lies and rage to poison and incapacitate the consciences of millions of Americans. Those who care about the common good are still, I believe, in the majority, but that means nothing if we lack the means and the will to be connected with one another in public truth-telling, mutual encouragement, and collective action. As long as we feel isolated, alone and discouraged, tyranny will flourish.

I was also struck by the importance of imagining alternatives to consensus reality in our public life. A sense of inevitability is the mother of inaction. In France under Louis XIV, the monarchy seemed inevitable—until it didn’t. In America, at least until Trump, democracy and the rule of law were assumed to be inevitable. And while many of us have come to realize how fragile and conditional our democracy actually is, the press, along with many Democratic politicians, continue to play the game of “Let’s Pretend.”

Let’s pretend that everyone is playing by the same rules. Let’s pretend the president is not fascist, childish, ignorant, cruel, and increasingly incoherent and nonsensical. Let’s pretend that normal protocols are the best way to engage with him. Let’s pretend we don’t have an American gestapo, or a White House dominated by racists, white nationalists and shameless liars. Let’s pretend our government isn’t supporting genocide in Gaza, or robbing millions of their health care. Let’s pretend that climate change is nothing to worry about. Let’s pretend it’s all just politics as usual and both sides do the same thing, so there’s no cause for alarm.

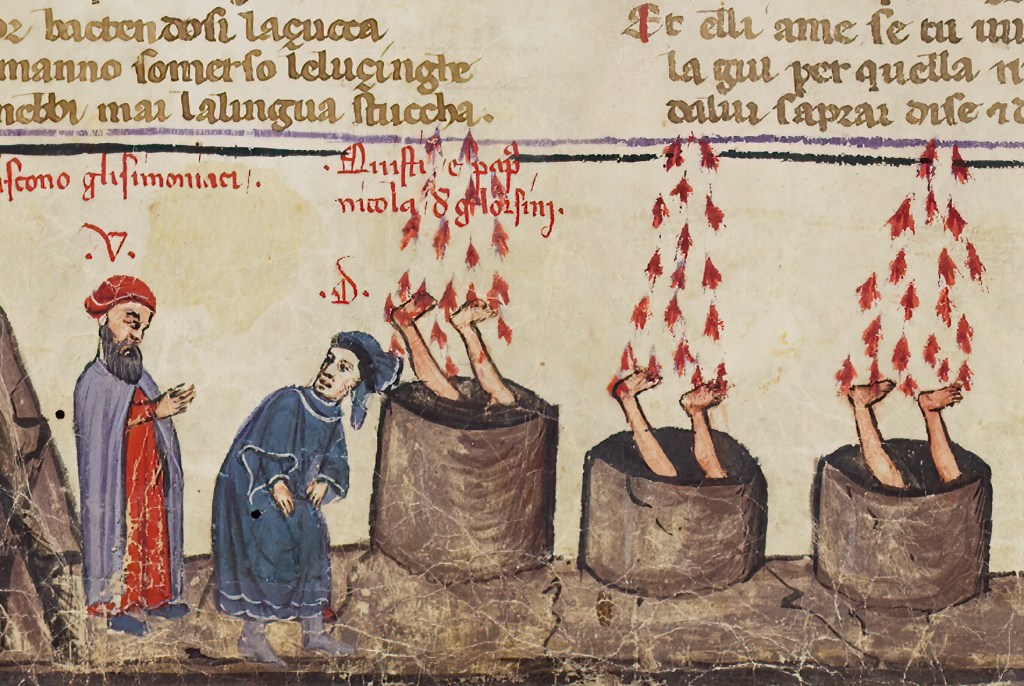

Finally, I was intrigued by the theatricality of what the French called emotions populaires [mass protests]. Straw effigies of unpopular or disgraced officials were mocked, paraded through the streets, and forced to kneel before statues of honored officials and beg divine pardon. On one occasion, the crowd seized a passing priest, demanding that he hear the dummy’s confession. Eyed with suspicion as a symbol of the Ancien Régime, the priest was careful not to anger the crowd by refusing to play. He put his ear to the effigy’s mouth for a few moments, then declared to all that it had so many sins to confess that it would take all night! The people laughed, applauded the priest’s wit, and let him go. As for the dummy official, he “was pitched into a giant feu de foie [‘fire of joy’].” [ix]

I suspect that setting fire to effigies of our American tyrants would not be a safe practice these days, and I am aware that the emotions populaires in revolutionary Paris often led to serious violence. But I wonder if there might be, in our own acts of resistance and witness, creative theatrical ways to engage with flanks of armed soldiers or gangs of ICE agents using guerilla theater, humor, song, ritual, and even clowning and mime—anything to subvert, disarm, or transcend the deadly Punch and Judy face-off of venomous gazes. Is there any way to make the other laugh, or wonder, or think, if only for a moment? Send in the clowns! Could you still want to shoot someone who made you laugh—or cry?

You may say that I’m a dreamer, but I’m not (I hope) the only one.

[i] Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804-1869), a French literary critic, is quoted by George Eliot in Impressions of Theophrastus Such; cited in Frederick Brown, The Embrace of Unreason: France, 1914-1940 (New York: Anchor Books, 2014), 3.

[ii] Robert Darnton, The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748-1789 (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2024), xix.

[iii] Ibid., 131.

[iv] Ibid., 333.

[v] Ibid., 390.

[vi] Ibid., 366.

[vii] Ibid., 400.

[viii] Ibid., 391.

[ix] Ibid., 371.