This new Israel the Lord brought by a mighty hand and an outstretched arm over a greater than the Red Sea, and gave them these ends of the earth for their habitation. In a day, with a wonderful alteration such as was never heard of in the world, the remote, rocky, bushy, wild-woody wilderness became for fertileness the wonder of the world, a second Eden, rejoicing and blossoming as a Rose, Beautiful as Tizrah, Comely as Jerusalem.

— A New England sermon, 17th century

Adam saw it in a brighter sunshine, but never knew the shade of pensive beauty which Eden won from his expulsion.

— Nathanael Hawthorne, The Marble Faun

Forty years ago, traveling in an old school bus with four other humans and two dogs, I visited New England communes to engage in dialogue about the nature of community. The project, funded by the Episcopal Church, was conceived by the Rev. Bill Teska, a fellow priest who thought the Church had something to learn from grassroots experiments in the nurturing of a common life.

It was November. Snow was beginning to blanket the land. Whenever we had to sleep in our chilly bus, I regretted that we were one animal short of a three-dog night. New England freezes will test the soul. At a newly-formed commune in Maine, we wondered how their experiment was going. “Ask us in the spring,” they told us. “We haven’t gone through our first winter yet. A commune hasn’t proved it can survive until it’s been through a winter.”

The United States of America has survived some pretty severe winters of discontent, but the storms brewing now have us all on edge in a way that feels unprecedented. We have begun to doubt our survival.

In reading Colm Toíbín’s The Magician, a novel about the life of Thomas Mann, I was struck by a couple of paragraphs describing Germany in 1934. With a few word changes, they could have been ripped from the headlines of America today:

“Each morning, as they read the newspapers over breakfast, one of them would share an item, a fresh outrage committed by the Nazis, an arrest or confiscation of property, a threat to the peace of Europe, an outlandish claim against the Jewish population or against writers and artists or against Communists, and they would sigh or grow silent. On some days, while reading out an item of news, Katia would say that this was the worst, only to be corrected by Erika, who would have found something even more outrageous.”

“The Nazis … were street fighters who had taken power without losing their sway over the streets. They managed to be both government and opposition. They thrived on the idea of enemies, including enemies within. They did not fear bad publicity—rather, they actually wanted the worst of their actions to become widely known, all the better to make everyone, even those loyal to them, afraid.” [i]

Sound familiar? What decent soul has not been worn down by the relentless succession of lies, madness, and evil acts over the past five years? And who does not now tremble at the increasingly overt embrace of violence, fear and hatred as acceptable political tools by a major political party?

I was born 6 weeks after D-Day. Although I have lived through some troubled times in America, I have never doubted my country’s ability to survive its sins—until this year. Suddenly the American experiment seems shockingly fragile and strangely impermanent. While the majority of Americans may still desire the greater good, the proliferation of bad actors, along with their enablers and dupes, has metastasized into the tens of millions. Our democracy managed to survive January 6th, but not by what anyone could call a comfortable margin. The party that enabled and even fomented insurrection not only refuses to show a shred of shame or remorse, it is actively working to undermine whatever defenses—like voting rights, or an impartial judiciary—remain against future coup attempts.

There is not yet a majority in Congress willing to overturn an election. Nor is a military takeover currently in the cards. But such scenarios are no longer utterly inconceivable. The smell of burning books is already in the air. Where do we go from here?

When the demons run wild in our common life, we cry, “This is not who we are!” The myth of American innocence has been a prevalent theme since the first colonists arrived in the “New World.” Freed of the dead weight of the past, armed with a sense of limitless possibility and buoyant resilience, we (i.e., white Americans) have preferred to think of ourselves as forever young.

The American, according to the myth, is the new Adam (or Eve) in the new Eden, a “radically new personality, the hero of the new adventure: an individual emancipated from history, happily bereft of ancestry, untouched and undefiled by the usual inheritances of family and race; an individual standing alone, self-reliant and self-propelling, ready to confront whatever awaited him with the aid of his own unique and inherent resources.” [ii]

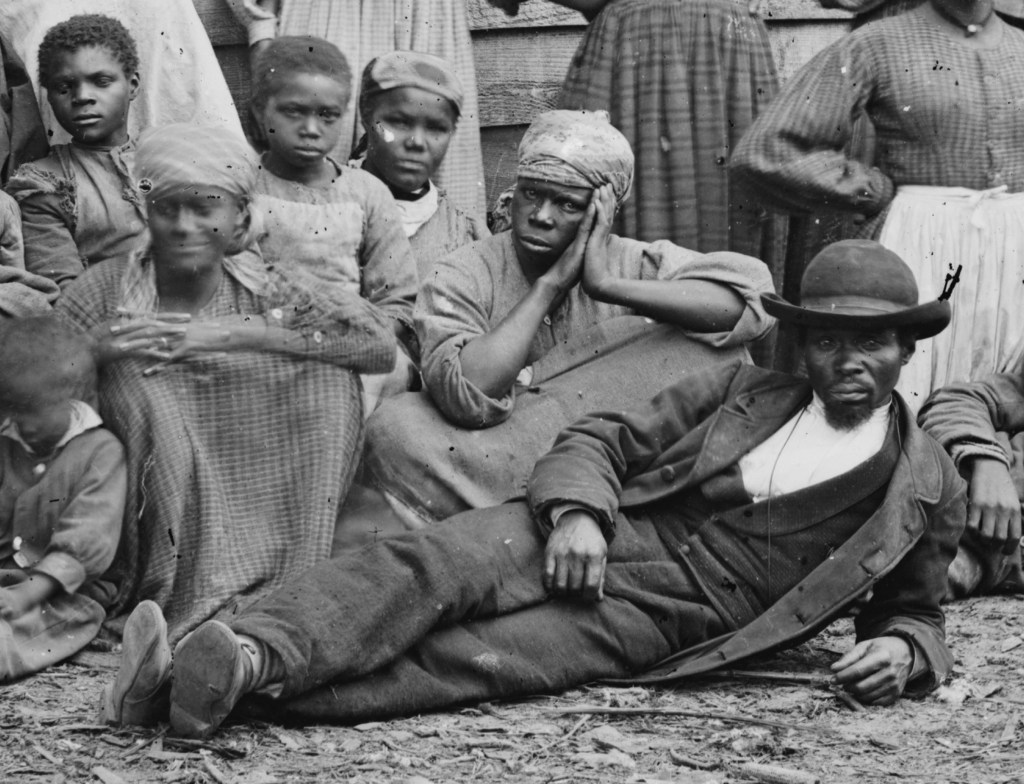

However, the preservation of this myth requires an immense labor of forgetting. Slavery, racism, the Native American genocide, xenophobia, mob violence, misogyny, environmental destruction and countless other sins do not fit the narrative of innocence. If myth’s stabilizing power lies in both conscious and unconscious agreement about our collective memory (“This is who we are!”), stirring up the troubling ghosts of historical evidence poses a threat to our sense of cohesion and identity. Tradition loses its binding force if it is allowed to be put into question.

“Don’t mess with our myths!” is the rallying cry of the far right, who have shown their willingness to destroy America in order to save their version of it. But the rest of us should not feel too secure within our own fictions of innocence. We have yet to resolve our legacy of racism. We seem incapable of addressing our propensity for violence. And our lifelong assumptions about American democracy have been plunged into doubt. When fascism infected Europe in the 1930s, Americans said, “It can’t happen here.” In these latter days, we know better. It can.

Okay, this all seems a little grim for Thanksgiving Eve. But if our current crisis forces us to reexamine and reform the foundations of our common life, perhaps we can be thankful for that. For people of faith, the survival of life as we know it is never the highest good. As we reminded ourselves last Sunday on the Feast of Christ the King, we are not in charge of history, and don’t have to be in love with particular outcomes of transitory events. Empires rise, empires fall. The Kingdom of God—the reign of self-diffusive love—is the only thing that endures, because it knows the secret of dying and rising. Therefore, even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia! [iii]

Even as the mountains tumble into the sea, the holy Mystery whispers “Rise! Rise!” into every moment, even the most forlorn. For that, I give thanks.

God is our refuge and strength,

a very present help in trouble.

Therefore we will not fear, though the earth be moved,

or the mountains tumble into the sea;

though the waters of chaos rage and foam,

though the mountains tremble at its tumult,

the Lord of hosts is with us; the God of Jacob is our stronghold.

— Psalm 46: 1-4

Previous Thanksgiving posts:

Utopian Dreams and Cold Realities: A Thanksgiving Homily

Trying to Get Home for Thanksgiving

[i] Colm Toíbín, The Magician (New York: Scribner, 2021), 229 & 231.

[ii] R. W. B. Lewis, The American Adam: Innocence, Tragedy, and Tradition in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955), 5.

[iii] The Burial Office, Episcopal Book of Common Prayer, 499.